PLN briefly mentioned in article about jail medical care in FL

Ocala Star-Banner, Jan. 1, 2007.

http://www.ocala.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=...

PLN briefly mentioned in article about jail medical care in FL - Ocala Star-Banner 2007

Article published Dec 17, 2007

Community care

After a contract dispute with the Marion County Jail health care provider, Sheriff Ed Dean decided to look to local health facilities as a way to treat the incarcerated.

BY NASEEM S. MILLER

STAR-BANNER

OCALA - At the stroke of midnight on Jan. 2, the Marion County Jail and local health care providers together will launch a new and unique system to care for the medical needs of inmates.

Ocala Community Care, Inc., an organization created by Sheriff Ed Dean, will collaborate with local health care providers to extend inmate health care beyond the jail's steel bars, and eventually incorporate it into the community's health care system.

The change will make MCJ one of the few jails in the nation to implement such a program, which is modeled after a community-based health system that got its start in a Massachusetts correctional center.

OCC will replace Prison Health Services, the Tennessee-based private company that has provided health care at the jail for the past two years. As one of the largest private providers of correctional health care, PHS has been the subject of frequent complaints and lawsuits over the quality of care here and around the nation.

Critics say private companies like PHS cut corners when it comes to providing medical care to inmates in order to save money and keep their investors happy. In addition, companies like PHS bring their own doctors and psychiatrists to the jail, and most of them have no connection to local health providers and don't have privileges at local hospitals, creating a gap in inmates' medical care after they're released.

Dean hopes to address these issues with the new model and keep the taxpayers' money in the community. "And if issues arise in the future, we will have enough local professionals to determine what changes need to be made."

PRISONERS' HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Despite general public apathy toward those behind bars, the issue of inmate health is of concern to more than just the inmates themselves and their families.

Almost 95 percent of inmates are eventually released back to their neighborhoods. More than 1.5 million people are released from jail every year with a communicable disease and more than 10 percent of the jail population has one or more serious mental illnesses. Roughly 80 percent have used illicit drugs at some point in their lives.

Combine high rates of disease and mental illness among inmates with often inadequate funding for correctional health care and the result is a system that endangers prisoners, staff and the public, according to a 2006 report by the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons, which is funded by the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit group devoted to educating the public and government on prison issues.

In recent years, there has been increased attention by health officials and other experts on the importance of connecting inmate health care to the community. According to the Commission's report and former acting surgeon general Dr. Kenneth Moritsugu, building a bridge between correctional health care and the community ensures the health and safety of everyone.

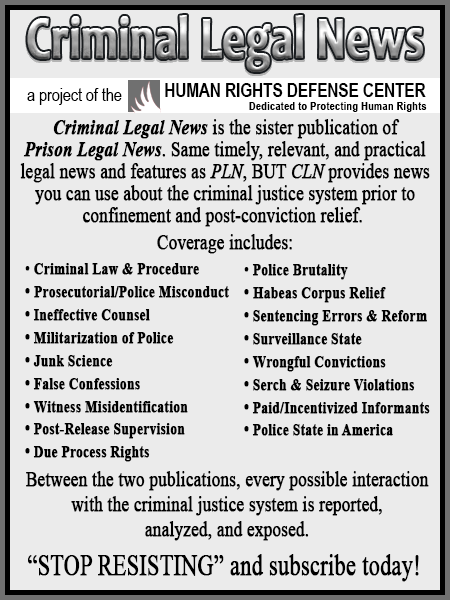

The tuberculosis infection rate in the United States is only 4.6 per 100,000 population, but approximately 90 percent of known cases occur among prisoners, according to data gathered by Prison Legal News, an independent monthly magazine that provides review and analysis of prisoner rights, court rulings and news about prison issues. Approximately 39 percent of Americans with hepatitis C cycle through prisons and jails each year, PLN reports. Many are also infected with HIV.

Most recently, MRSA, an antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria, has been spreading through jails and prisons, infecting not only inmates, but officers and their families.

So correctional facilities have a tremendous opportunity to provide health care to people in jail and prisons that also protects the public health, the Commission report points out.

CREATING COMMUNITY CARE

Several studies have shown that the model Dean is using can lead to cost savings, improved inmate and public health, reduced recidivism and improved public safety.

PHS officials would not agree to be interviewed for this story. The company did respond to questions submitted in writing and expressed doubt about the potential for a successful community-oriented correctional health care program.

"[It] is an interesting proposition, although we have not seen such an approach work in other areas due to massive cost overruns and lack of experience in a correctional setting," PHS stated in an e-mail sent by Martha Harbin, PHS's media liaison for Florida. "Correctional health care is a unique area, where experience is critical to success."

Dean admits that no one knows how this new venture will work. "It's easy for people to say it won't work, because it's never been tried here," he said.

But he is aiming high, hoping to create a system that will serve as a model for inmate health care in Florida.

Establishing a community-based inmate health care system is complex and requires the participation of local institutions such as the hospitals and the county Health Department, factors that have turned off the interest of local governments around the nation.

But this isn't the first time Dean has led an effort to find creative ways of providing health care for people in tough circumstances. More than a decade ago, he helped establish Community Health Services, a local clinic that provides care to residents who are at or below 125 percent of federal poverty guidelines or on Medicaid.

He managed to pull together major community leaders and care providers quickly after he decided in July not to renew PHS' contract due to a disagreement over the cost of the contract for the coming year. In a matter of six months OCC was incorporated and is now ready to launch.

The $4.9 million that would have gone to PHS, will instead go to OCC to cover costs for its first year of service. The board will meet annually to look at the previous year's expenses and decide on next year's budget, They hope the nonprofit system will help them keep costs at or below what would have been paid to a private company.

A major collaborator in the OCC contract is The Centers, the mental health provider in the county.

"Sometimes, because of their mental illness, people wind up getting in trouble," said Russell Rasco, CEO of The Centers, who also sits on the OCC board.

Rasco said a portion of inmates with mental illness have already been to The Centers to receive treatment. "But the missing component is helping these individuals while they're in jail."

With the departure of PHS, The Centers will send in two psychiatrists to the jail. As a result, inmates with mental illness have the opportunity not to ever leave the care of The Centers, Rasco said. Such continuity of care did not exist under PHS, which brought in its own psychiatrist, who is not located in Marion County.

The new medical director of the jail is Dr. Ketheeswaran Kathiripillai, who works at Munroe Regional Medical Center and has admission and discharge privileges there for inmates who have to be taken to the hospital. The contract requires him to be at the jail 15 hours a week to oversee the infirmary, see patients and review charts.

"We hope that based upon on Dr. Kath's ability to have lateral movement, that will allow improved efficiencies and care management," said Phil Hoelscher, president of Alliance Medical Management. Dean hired him to monitor PHS' contract. He has helped draw up OCC's contract with the Sheriff's Office and will continue to monitor it.

Dr. Sinclair Short, who has been the on-site dentist with PHS, now has a contract with OCC to provide dental services 15 hours a week.

OCC also has contracts with a staffing agency that will pay the rest of the clinical staff. More than 90 percent of the nursing staff has decided to stay after PHS leaves January 2.

Other components of the contract include radiology, laboratory and pharmacy services.

Eight members of the community sit on the OCC board, including Steve Purves, CEO of Munroe Regional, and a representative from the Marion County Medical Society.

The only missing component is a community health center (Federally Qualified Health Center) that would connect to OCC.

Another local nonprofit group called Heart of Florida Health Center, led by Dyer Michell, former CEO of Munroe Regional, applied for the FQHC this month, but the results won't be announced until August next year.

If the county gets the federal health center grant, the ultimate goal is to join OCC to it.

An FQHC provides care to everyone regardless of their income or insurance, and given the fact that most of the inmate population is uninsured, "they would most probably benefit from FQHC's services," Hoelscher said.

A SUCCESSFUL MODEL

OCC is modeled after an award-winning program that was established in Hampden County Correctional Center in Ludlow, Mass., more than a decade ago.

The objective of the HCCC's model is to provide comprehensive health care services beginning within the first days of incarceration and continuing after an inmates' release.

It all started with an HIV-positive patient in Springfield, Mass., who missed his appointment at the local community health center.

Concerned, the man's doctor called his house and found out that he was locked up at the HCCC. So, he asked the sheriff if he could continue treating his patient at the facility.

Sheriff Michael Ashe agreed.

"But then he took a step back and looked at where the inmates came from," said Paul Sheehan, who was in charge of establishing community programs at the HCCC until recently.

"He realized they were coming from four ZIP Codes and each [ZIP Code] had a health center. So he figured rather than treating the jail as a temporary home, why not use it as an opportunity to provide public and community health care?" Sheehan said.

Until then, the correctional facility, run by the Sheriff's Office, contracted with individual doctors.

It took HCCC three years to create contracts with the four health centers. The correctional center eventually became more of a satellite for the health centers. "And the biggest part of it is [helping] inmates set up appointments for after their release," said Sheehan.

Aside from community health centers, the HCCC has contracts with local mental health providers, dentists and optometrists that provide care at the jail and in the community.

Teams of doctors, nurses and case managers work both in the correctional facility and in the community. Inmates are assigned to the team that matches their ZIP Code.

A 2001 study published by the U.S. Department of Justice showed that HCCC, when compared to 17 other jails around the nation, ranked third lowest in total health care expenditures, third lowest in the percent of its overall budget devoted to health care costs and ninth lowest in annual health care cost per inmate. The study was based on 1998 data.

In addition more than half of the inmates follow up with their appointments after they're released, which helps improve their health, and also the community's health.

"So many people cycle through that it does present an opportunity to capture a lot of chronically ill people and a good way to do that is to maximize use of community health center network," Sheehan said.

AN IDEA SPREADS

The Hampden County Correctional Center's inmate health-care model has won several awards, including the Innovation in American Government Award from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

An assessment of the program showed that the community health model leads to improved inmate health, improved public safety and public health, better use of the health care system and also cost savings, because sick inmates won't end up at the emergency rooms after they're released.

The model has been impressive enough that the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation boosted the idea with a $7.4 million grant to form a nonprofit organization called Community-Oriented Correctional Health Services, or COCHS, based in Oakland, Calif. The organization works with jail and health center officials to help them implement the complex model.

COCHS' executives made several trips to Ocala and provided insight and advice to OCC board members.

"Our ultimate goal is to make sure that the community health network will definitely be considered as an option for every community that's considering local correctional health care delivery. If every sheriff who's looking to make a change, they think right away, let's talk to our community health provider. That'll be great," said Sheehan, who is now the chief operating officer of COCHS.

"Regardless of how people feel about inmates, they're part of our community," he said. "They're displaced members of the community and they all come back."

Article published Dec 17, 2007

Community care

After a contract dispute with the Marion County Jail health care provider, Sheriff Ed Dean decided to look to local health facilities as a way to treat the incarcerated.

BY NASEEM S. MILLER

STAR-BANNER

OCALA - At the stroke of midnight on Jan. 2, the Marion County Jail and local health care providers together will launch a new and unique system to care for the medical needs of inmates.

Ocala Community Care, Inc., an organization created by Sheriff Ed Dean, will collaborate with local health care providers to extend inmate health care beyond the jail's steel bars, and eventually incorporate it into the community's health care system.

The change will make MCJ one of the few jails in the nation to implement such a program, which is modeled after a community-based health system that got its start in a Massachusetts correctional center.

OCC will replace Prison Health Services, the Tennessee-based private company that has provided health care at the jail for the past two years. As one of the largest private providers of correctional health care, PHS has been the subject of frequent complaints and lawsuits over the quality of care here and around the nation.

Critics say private companies like PHS cut corners when it comes to providing medical care to inmates in order to save money and keep their investors happy. In addition, companies like PHS bring their own doctors and psychiatrists to the jail, and most of them have no connection to local health providers and don't have privileges at local hospitals, creating a gap in inmates' medical care after they're released.

Dean hopes to address these issues with the new model and keep the taxpayers' money in the community. "And if issues arise in the future, we will have enough local professionals to determine what changes need to be made."

PRISONERS' HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH

Despite general public apathy toward those behind bars, the issue of inmate health is of concern to more than just the inmates themselves and their families.

Almost 95 percent of inmates are eventually released back to their neighborhoods. More than 1.5 million people are released from jail every year with a communicable disease and more than 10 percent of the jail population has one or more serious mental illnesses. Roughly 80 percent have used illicit drugs at some point in their lives.

Combine high rates of disease and mental illness among inmates with often inadequate funding for correctional health care and the result is a system that endangers prisoners, staff and the public, according to a 2006 report by the Commission on Safety and Abuse in America's Prisons, which is funded by the Vera Institute of Justice, a nonprofit group devoted to educating the public and government on prison issues.

In recent years, there has been increased attention by health officials and other experts on the importance of connecting inmate health care to the community. According to the Commission's report and former acting surgeon general Dr. Kenneth Moritsugu, building a bridge between correctional health care and the community ensures the health and safety of everyone.

The tuberculosis infection rate in the United States is only 4.6 per 100,000 population, but approximately 90 percent of known cases occur among prisoners, according to data gathered by Prison Legal News, an independent monthly magazine that provides review and analysis of prisoner rights, court rulings and news about prison issues. Approximately 39 percent of Americans with hepatitis C cycle through prisons and jails each year, PLN reports. Many are also infected with HIV.

Most recently, MRSA, an antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria, has been spreading through jails and prisons, infecting not only inmates, but officers and their families.

So correctional facilities have a tremendous opportunity to provide health care to people in jail and prisons that also protects the public health, the Commission report points out.

CREATING COMMUNITY CARE

Several studies have shown that the model Dean is using can lead to cost savings, improved inmate and public health, reduced recidivism and improved public safety.

PHS officials would not agree to be interviewed for this story. The company did respond to questions submitted in writing and expressed doubt about the potential for a successful community-oriented correctional health care program.

"[It] is an interesting proposition, although we have not seen such an approach work in other areas due to massive cost overruns and lack of experience in a correctional setting," PHS stated in an e-mail sent by Martha Harbin, PHS's media liaison for Florida. "Correctional health care is a unique area, where experience is critical to success."

Dean admits that no one knows how this new venture will work. "It's easy for people to say it won't work, because it's never been tried here," he said.

But he is aiming high, hoping to create a system that will serve as a model for inmate health care in Florida.

Establishing a community-based inmate health care system is complex and requires the participation of local institutions such as the hospitals and the county Health Department, factors that have turned off the interest of local governments around the nation.

But this isn't the first time Dean has led an effort to find creative ways of providing health care for people in tough circumstances. More than a decade ago, he helped establish Community Health Services, a local clinic that provides care to residents who are at or below 125 percent of federal poverty guidelines or on Medicaid.

He managed to pull together major community leaders and care providers quickly after he decided in July not to renew PHS' contract due to a disagreement over the cost of the contract for the coming year. In a matter of six months OCC was incorporated and is now ready to launch.

The $4.9 million that would have gone to PHS, will instead go to OCC to cover costs for its first year of service. The board will meet annually to look at the previous year's expenses and decide on next year's budget, They hope the nonprofit system will help them keep costs at or below what would have been paid to a private company.

A major collaborator in the OCC contract is The Centers, the mental health provider in the county.

"Sometimes, because of their mental illness, people wind up getting in trouble," said Russell Rasco, CEO of The Centers, who also sits on the OCC board.

Rasco said a portion of inmates with mental illness have already been to The Centers to receive treatment. "But the missing component is helping these individuals while they're in jail."

With the departure of PHS, The Centers will send in two psychiatrists to the jail. As a result, inmates with mental illness have the opportunity not to ever leave the care of The Centers, Rasco said. Such continuity of care did not exist under PHS, which brought in its own psychiatrist, who is not located in Marion County.

The new medical director of the jail is Dr. Ketheeswaran Kathiripillai, who works at Munroe Regional Medical Center and has admission and discharge privileges there for inmates who have to be taken to the hospital. The contract requires him to be at the jail 15 hours a week to oversee the infirmary, see patients and review charts.

"We hope that based upon on Dr. Kath's ability to have lateral movement, that will allow improved efficiencies and care management," said Phil Hoelscher, president of Alliance Medical Management. Dean hired him to monitor PHS' contract. He has helped draw up OCC's contract with the Sheriff's Office and will continue to monitor it.

Dr. Sinclair Short, who has been the on-site dentist with PHS, now has a contract with OCC to provide dental services 15 hours a week.

OCC also has contracts with a staffing agency that will pay the rest of the clinical staff. More than 90 percent of the nursing staff has decided to stay after PHS leaves January 2.

Other components of the contract include radiology, laboratory and pharmacy services.

Eight members of the community sit on the OCC board, including Steve Purves, CEO of Munroe Regional, and a representative from the Marion County Medical Society.

The only missing component is a community health center (Federally Qualified Health Center) that would connect to OCC.

Another local nonprofit group called Heart of Florida Health Center, led by Dyer Michell, former CEO of Munroe Regional, applied for the FQHC this month, but the results won't be announced until August next year.

If the county gets the federal health center grant, the ultimate goal is to join OCC to it.

An FQHC provides care to everyone regardless of their income or insurance, and given the fact that most of the inmate population is uninsured, "they would most probably benefit from FQHC's services," Hoelscher said.

A SUCCESSFUL MODEL

OCC is modeled after an award-winning program that was established in Hampden County Correctional Center in Ludlow, Mass., more than a decade ago.

The objective of the HCCC's model is to provide comprehensive health care services beginning within the first days of incarceration and continuing after an inmates' release.

It all started with an HIV-positive patient in Springfield, Mass., who missed his appointment at the local community health center.

Concerned, the man's doctor called his house and found out that he was locked up at the HCCC. So, he asked the sheriff if he could continue treating his patient at the facility.

Sheriff Michael Ashe agreed.

"But then he took a step back and looked at where the inmates came from," said Paul Sheehan, who was in charge of establishing community programs at the HCCC until recently.

"He realized they were coming from four ZIP Codes and each [ZIP Code] had a health center. So he figured rather than treating the jail as a temporary home, why not use it as an opportunity to provide public and community health care?" Sheehan said.

Until then, the correctional facility, run by the Sheriff's Office, contracted with individual doctors.

It took HCCC three years to create contracts with the four health centers. The correctional center eventually became more of a satellite for the health centers. "And the biggest part of it is [helping] inmates set up appointments for after their release," said Sheehan.

Aside from community health centers, the HCCC has contracts with local mental health providers, dentists and optometrists that provide care at the jail and in the community.

Teams of doctors, nurses and case managers work both in the correctional facility and in the community. Inmates are assigned to the team that matches their ZIP Code.

A 2001 study published by the U.S. Department of Justice showed that HCCC, when compared to 17 other jails around the nation, ranked third lowest in total health care expenditures, third lowest in the percent of its overall budget devoted to health care costs and ninth lowest in annual health care cost per inmate. The study was based on 1998 data.

In addition more than half of the inmates follow up with their appointments after they're released, which helps improve their health, and also the community's health.

"So many people cycle through that it does present an opportunity to capture a lot of chronically ill people and a good way to do that is to maximize use of community health center network," Sheehan said.

AN IDEA SPREADS

The Hampden County Correctional Center's inmate health-care model has won several awards, including the Innovation in American Government Award from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

An assessment of the program showed that the community health model leads to improved inmate health, improved public safety and public health, better use of the health care system and also cost savings, because sick inmates won't end up at the emergency rooms after they're released.

The model has been impressive enough that the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation boosted the idea with a $7.4 million grant to form a nonprofit organization called Community-Oriented Correctional Health Services, or COCHS, based in Oakland, Calif. The organization works with jail and health center officials to help them implement the complex model.

COCHS' executives made several trips to Ocala and provided insight and advice to OCC board members.

"Our ultimate goal is to make sure that the community health network will definitely be considered as an option for every community that's considering local correctional health care delivery. If every sheriff who's looking to make a change, they think right away, let's talk to our community health provider. That'll be great," said Sheehan, who is now the chief operating officer of COCHS.

"Regardless of how people feel about inmates, they're part of our community," he said. "They're displaced members of the community and they all come back."