PLN mentioned in article about restricting felons' access to public records

News Tribune, Jan. 1, 2008.

http://www.thenewstribune.com/opinion/v-printer...

PLN mentioned in article about restricting felons' access to public records - News Tribune 2008

Tacoma, WA - Thursday, June 12, 2008

Restrict, don’t ban felons’ records demands

THE NEWS TRIBUNE

Last updated: June 12th, 2008 01:24 AM (PDT)

Attorney General Rob McKenna thinks prison inmates should not be able to pervert the public records law to harass members of the criminal justice system.

He’s absolutely right.

Problem is, McKenna’s reading of the state Public Records Act pushes Washington too far the other way.

The essence of McKenna’s argument, explained in a friend-of-the-court brief filed last week, is that an incarcerated felon is not a “person” for purposes of the state open records law.

His reasoning: Felons forfeit many of the civil rights that allow them to keep government in check. They have already yielded the sovereignty that the Public Records Act seeks to protect.

Placing public records out of inmates’ reach would certainly stop the likes of Allan Parmelee. He’s a King County arsonist bent on using the public records law as a bludgeon. Ever since he was sentenced to 24 years for firebombing the cars of two lawyers, Parmelee has whiled away his time by filing public records requests, hundreds of them.

The requests target judges, lawyers and corrections officers that have crossed paths with Parmelee. He demands their personnel records, photos, addresses, schedules, birth dates. It’s a clear attempt to intimidate and harass.

The Court of Appeals, now considering a case involving some of Parmelee’s requests, asked McKenna to weigh in on whether inmates should have standing to request documents under the Public Records Act.

If the court adopts McKenna’s legal interpretation, it would keep thugs like Parmelee from corrupting the open records law. But it also would cut off access for prisoners like Paul Wright, who founded and edited Prison Legal News from behind bars. Even with the open records law on his side, Wright had to pursue the Department of Corrections all the way to the state Supreme Court to find out who had treated 10 inmates who’d wound up seriously injured or dead.

Some limits are due. Between the extremes of Parmelee and Wright are a whole lot of bored prisoners who make a mockery of open government with requests for information as meaningless as how many plastic bags the Department of Corrections purchases.

Corrections staff spent more than 12,000 hours responding to 4,917 requests from offenders last year. The public subsidizes such mischief with tax dollars and time spent waiting in longer records queues.

But a court ruling is a blunt instrument. Not only might the court bar all inmate access, it also could extend that restriction to convicts who have already done their time. McKenna attempted to limit his argument to prisoners behind bars, but the way the Court of Appeals framed its question raises the possibility that felons who haven’t gone to the trouble of getting their civil rights restored would also suffer the loss of public records access.

The Legislature is better equipped than the courts to walk the fine line between preventing abuses and preserving access for legitimate records requests. McKenna admits as much, pointing out that he interpreted the law as he found it, not as it should be.

Whatever the Court of Appeals makes of McKenna’s legal arguments, lawmakers have a job to do when they convene next January. On our blog To read McKenna’s brief, go to the Inside the Editorial Page blog at blogs.thenewstribune.com/oped.

Tacoma, WA - Thursday, June 12, 2008

Restrict, don’t ban felons’ records demands

THE NEWS TRIBUNE

Last updated: June 12th, 2008 01:24 AM (PDT)

Attorney General Rob McKenna thinks prison inmates should not be able to pervert the public records law to harass members of the criminal justice system.

He’s absolutely right.

Problem is, McKenna’s reading of the state Public Records Act pushes Washington too far the other way.

The essence of McKenna’s argument, explained in a friend-of-the-court brief filed last week, is that an incarcerated felon is not a “person” for purposes of the state open records law.

His reasoning: Felons forfeit many of the civil rights that allow them to keep government in check. They have already yielded the sovereignty that the Public Records Act seeks to protect.

Placing public records out of inmates’ reach would certainly stop the likes of Allan Parmelee. He’s a King County arsonist bent on using the public records law as a bludgeon. Ever since he was sentenced to 24 years for firebombing the cars of two lawyers, Parmelee has whiled away his time by filing public records requests, hundreds of them.

The requests target judges, lawyers and corrections officers that have crossed paths with Parmelee. He demands their personnel records, photos, addresses, schedules, birth dates. It’s a clear attempt to intimidate and harass.

The Court of Appeals, now considering a case involving some of Parmelee’s requests, asked McKenna to weigh in on whether inmates should have standing to request documents under the Public Records Act.

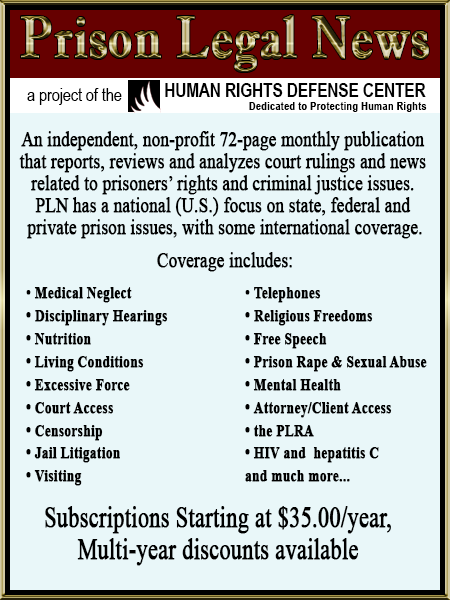

If the court adopts McKenna’s legal interpretation, it would keep thugs like Parmelee from corrupting the open records law. But it also would cut off access for prisoners like Paul Wright, who founded and edited Prison Legal News from behind bars. Even with the open records law on his side, Wright had to pursue the Department of Corrections all the way to the state Supreme Court to find out who had treated 10 inmates who’d wound up seriously injured or dead.

Some limits are due. Between the extremes of Parmelee and Wright are a whole lot of bored prisoners who make a mockery of open government with requests for information as meaningless as how many plastic bags the Department of Corrections purchases.

Corrections staff spent more than 12,000 hours responding to 4,917 requests from offenders last year. The public subsidizes such mischief with tax dollars and time spent waiting in longer records queues.

But a court ruling is a blunt instrument. Not only might the court bar all inmate access, it also could extend that restriction to convicts who have already done their time. McKenna attempted to limit his argument to prisoners behind bars, but the way the Court of Appeals framed its question raises the possibility that felons who haven’t gone to the trouble of getting their civil rights restored would also suffer the loss of public records access.

The Legislature is better equipped than the courts to walk the fine line between preventing abuses and preserving access for legitimate records requests. McKenna admits as much, pointing out that he interpreted the law as he found it, not as it should be.

Whatever the Court of Appeals makes of McKenna’s legal arguments, lawmakers have a job to do when they convene next January. On our blog To read McKenna’s brief, go to the Inside the Editorial Page blog at blogs.thenewstribune.com/oped.