The Illinois Department of Corrections benefits from a private contractor fleecing prisoners and their families by controlling phone services, according to three state lawmakers pushing legislation to limit what prisoners pay for phone calls. However, IDOC says the money it receives pays for certain inmate health care treatments.

Meanwhile, the private contractor recently settled a lawsuit alleging it illegally recorded calls between inmates and their attorneys, then turned the recordings over to prosecutors.

Rep. Carol Ammons, D-Champaign, sponsors HB6200, which would cap the charge for inmate calls at five cents per minute. The bill comes as the Federal Communications Commission fights prison phone contractors in federal court over rules the agency created last year to cap prison call charges.

Ammons said IDOC benefits from “kickbacks” drawn from what the agency’s sole phone contractor, Texas-based Securus Technologies, charges Illinois inmates. State law authorizes IDOC to collect the money, which the law refers to as “commissions.” Nicole Wilson, spokeswoman for the Illinois Department of Corrections, says the money helps pay for crucial programs to treat inmates with Hepatitis C, HIV, and AIDS.

Ammons’ bill would prohibit IDOC from collecting commissions on phone calls, and she has asked Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan to investigate the commissions.

IDOC anticipates around $12 million in commissions for the coming year. Until last year, IDOC only received about $5.5 million, and the rest went to the Illinois Department of Central Management Services. IDOC is slated to receive the full amount of its commission this year.

Inmates in Illinois prisons aren’t allowed to receive phone calls, and they can only make calls on a schedule to people on their pre-approved list. Calls are limited to 30 minutes. Inmates must purchase prepaid phone cards or call collect. In addition to paying for collect calls, families often send money to imprisoned loved ones.

Inmates in the custody of IDOC pay $3.55 for each 30-minute call. That includes a $3.35 charge for the first minute of each call, plus 1.5 cents per minute until minute 15. The rest of the call, from minute 16 through minute 30, is free. Wilson says the rate structure is a response to an FCC rule which banned flat-rate phone charges for inmate calls.

“With the previous vendor, it was not unusual for offenders’ families to pay between $6.31 and $9.70 for a 30-minute phone call,” Wilson said, adding that IDOC has no control over phone rates at local and county jails.

Under Ammons’ bill capping rates at five cents per minute, a 30-minute call within the state would cost $1.50 at most. The bill would outlaw other fees and charges, although it wouldn’t take effect until the current contract is up.

IDOC’s phone contractor, Securus, has faced allegations besides price gouging. In March, Securus settled a federal lawsuit filed in 2014, alleging the company illegally recorded confidential calls between inmates and attorneys. The lawsuit claimed those recordings were then disclosed to prosecutors. An attorney for Securus could not be reached for comment.

The Intercept, an online news website, in 2015 received a cache of 70 million call recordings leaked from Securus’ database. Around 57,000 of the recordings were of inmates and their attorneys, according to the website. The leak occurred after the Texas lawsuit was filed.

In 2014, an official in the Alaska Department of Corrections disclosed that an unknown number of attorney-client calls were recorded by Securus, although the official portrayed the recordings as accidental.

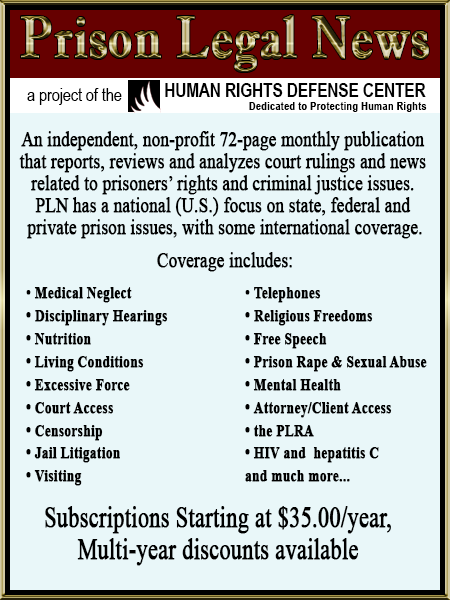

Carrie Wilkinson, director of the Prison Phone Justice Campaign for the Florida-based Human Rights Defense Center, says corrections agencies and county jails are as much to blame as Securus and other phone contractors for the prices inmates and their families pay. Wilkinson says correctional agencies often demand commissions as part of the contract. She says that when the state of New York eliminated commissions in 2008, the rate dropped to five cents per minute, and the volume of calls increased dramatically.

“The basic problem is that correctional agencies are the customer, not inmates or their families,” Wilkinson said. “Correctional industries are trying to jack the rates for kickbacks.”

Danielle Chynoweth, organizing director of the California-based Center for Media Justice, says research shows contact with families helps keep inmates from committing further crimes once released.

“The number one factor to avoid recidivism is contact with friends and family,” she said. “The phone call is the most important piece of that, because often in the state of Illinois, family members are scattered across the state, and they’re not able to see their loved ones in person. The phone call is the link; it’s the lifeline to their family members.”