PLN managing editor quoted in "In Natural Disasters, Are Inmates Expendable?"

In Natural Disasters, Are Inmates Expendable?

Oct. 3, 2017

Are prisons built to withstand the kinds of natural disasters that experts say will become more frequent and more intense as a result of climate change?

The short answer, according to prisoner advocates, is no.

When Hurricanes Harvey and Irma struck the southern United States this fall, prisons built years ago, in zones vulnerable to flooding, were directly in their path. Thousands of prisoners in Texas and Florida, which together house more than a quarter of a million inmates—approximately 16% of the U.S. prison population—had to be evacuated to more secure facilities.

But others were stranded, including the 1,812 male inmates of the federal low-security facility in Beaumont, Tx. Although authorities had decided the inmates in Beaumont had “sufficient food and water supply” to survive the flooding, later reports told a different story—of prisoners suffering from deteriorating conditions.

When Hurricane Maria battered Puerto Rico in late September, 13 prisoners at the federal prison in Guaynabo escaped during the evacuation of more than 1,300 inmates who had been trapped without food and power. As in the U.S. mainland, Puerto Rico historically constructed its prisons along coasts and near high-risk flood areas across the island.

The evacuations highlighted a worrying fact: correctional institutions rarely consider disaster-proofing in architectural plans for prisons in areas susceptible to natural disasters.

As climate changes forces itself into the forefront of disaster planning, coping with inmates trapped in often aging facilities that are literally on the front lines is emerging as both a humanitarian and public safety issue.

“Throughout history, prisons have always been located at the edge of civilization,” said Raphael Sperry, president of Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR).

“As much as American voters supported the expansion of criminal penalties and prison construction in the ’80s and ’90s, most every voting community also rejected new prisons being built in or near them.”

Sperry added that the traditional approach to building prisons far from populated areas has shielded them from public scrutiny.

These “edge of civilization” facilities are often in zones that are now at the greatest risk from increases in sea level as well as flooding, but prison designs place a premium on the security of civilians who live near them, rather than on the security or safety of those inside, according to Sperry.

The Beaumont facility, for example, was built in 1998 on Texas’ southeastern coast, and has never been upgraded to handle natural disasters, despite its location in a flood zone.

In a September 11 filing, the Prisoners Legal Advocacy Network (PLAN) cited numerous reports from prisoners and family members that inmates remained without access to toilet and showering facilities, adequate food and water, medication and outside communication.

As PLAN states, “The vulnerability of Texas prisons to hurricane conditions is a well-known and longstanding problem,” one which the Federal Bureau of Prisons chooses to ignore.

It wasn’t the first time the Beaumont prison was caught by a natural disaster.

When Hurricane Ike struck Texas in 2008, Beaumont inmates were forced to endure identical conditions – conditions so horrendous, that “in excess of 130 lawsuits were filed by prisoners…asserting that ‘the living conditions after the storm violated their civil rights,’” according to PLAN.

When Hurricane Rita hit the U.S. in 2005, more than 400 inmates in Beaumont’s maximum-security unit went days without food, running water or air conditioning. The prison cells flooded with sewage water and reached temperatures of nearly 100 degrees.

According to PLAN, the October 2014 FEMA Flood Risk Report for Jefferson County Coastal Project Area found that, in the vicinity of Beaumont prison, “Natural drainage is generally poor as many of the streams have shallow meandering channels…”

“Principal flooding problems include stream overflow cause by rainfall runoff, ponding, and sheet flow, and from tidal surges caused by hurricanes and tropical storms.”

Nevertheless, statements made by the Federal Bureau of Prisons during Hurricane Harvey declared that “all inmates remain safe in their housing units” and were receiving “an adequate food and water supply.

“The remarkable consistency in these allegations establishes convincingly both the seriousness of the situation at USP Beaumont, and the fact that rights-violating conditions persist(ed) even weeks after the storm,” said Paul Stanley Holdorf, supervising attorney for the PLAN project.

Holdorf went on to charge that federal authorities not only demonstrated “inadequate preparation for this foreseeable event” but failed to “uphold their most basic due diligence obligations to ensure safe and humane conditions for the human beings entrusted to their care.”

Natural disasters are a recurring threat for correctional institutions throughout the United States.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, sheriffs at the Orleans Parish Prison left 6,500 incarcerated people to fight for their survival in chest-high water.

According to a report by the American Civil Liberties Union, these prisoners were told they would be shot if they tried to escape from the flooding building.

In 2014, extreme flooding occurred at the Escambia County Central Booking and Detention Center in Florida due to severe rain storms. The flooding caused a natural gas explosion, severely damaging the jail, killing two inmates and injuring 184 inmates and correction officers.

But the new jail was built in the exact same spot.

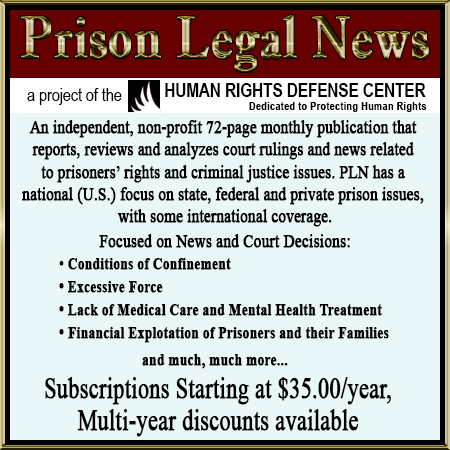

“This stuff really doesn’t enter the mind of policy makers in decision making,” said Alex Friedmann, Managing Editor of Prison Legal News – a project of the nonprofit Human Rights Defense Center.

“The bottom line is that prisoners are still basically seen as a fairly expendable population,” he added.

“Policymakers just don’t exhibit the same level of concern for inmates as they do with non-incarcerated residents. That basically has to do with the perception of prisoners and how we basically dehumanize them through mass incarceration.”

Friedmann emphasized that there are important lessons to be learned from natural disasters of the past and present. One critical issue that needs to be addressed, he told The Crime Report, is how outdated prisons are throughout the country.

“Most facilities are fairly ancient,” said Friedmann. “They might get updated, they might get repairs, but there’s an enormous amount of expense building a new prison. We still have 100- year-old prisons in the United States.”

Despite the conditions in Beaumont, both Texas and Florida combined were able to transport roughly 18,000 inmates to more secure areas from both state and local facilities. However for Friedmann, evacuating thousands of prisoners – instead of improving prison design – is not a practical solution.

“Texas did some enormous evacuations during Hurricane Harvey, and Florida did as well during Hurricane Irma,” said Friedmann.

Prisoners are completely reliant upon prison administrators for their safety and wellbeing. As the outside world prepares for natural disasters, inmates must await their fate from the confines of their cells.

Prisoner advocates say that this leads to additional punishment for prisoners beyond their sentences for crimes they committed, and they called for rethinking future prison construction.

But as a first step they urge policymakers to develop better plans for prisoner evacuations in the event of earthquakes, hurricanes and other disasters.

“Moving thousands of prisoners is a logistical nightmare,” said Friedmann. “Doing that safely while providing food, medication, shelter and so on—that’s an enormous undertaking.

“Typically, corrections agencies are not well-equipped to do that.”