PLN editor quoted in article following national prison strike

Why Did the National Prison Strike Float Under the Nation’s Radar?

|

The national prison strike that ended Sunday appears to have escaped the attention of most of the country’s lawmakers. Members of Congress responsible for national prison policy admitted to not knowing anything about the 19-day strike that began last month.

And the topic didn’t appear to have come up in the much-publicized White House meeting last week between President Donald Trump and public figures such as Kim Kardashian, which was ostensibly called to discuss prison reform as well as clemency policy.

Past prisoner actions, most notably the 1971 Attica Prison riot in upstate New York, whose 47th anniversary was marked on Sunday, have garnered major headlines. So why did this one float beneath the nation’s radar?

“That’s because it was a peaceful strike,” said Dr. Breea Willingham, a criminal justice professor at State University of New York at Plattsburgh.

“If people were getting killed inside those prisons, people would have been all over it.”

The relative lack of attention to the strike underlined the continued indifference to widespread claims of abuse and inhumane conditions inside the nation’s prison system, observers and prison activists told The Crime Report.

Last month’s protests mostly took the form of inmates refusing to eat, spend money at commissaries and work—but of there had been violence, similar to the Sept. 9, 1971 Attica Prison uprising, which took the lives of 43 people (including 33 inmates and 10 guards and civilian prison employees), it would probably have further harmed the inmates’ case, said Willingham, whose expertise includes the impact of incarceration on families, and race and crime in the media helped.

“(People) would have said ‘see, this is exactly why those prisoners need to be locked up,’” he said.

Perhaps another reason why the strike didn’t garner increased coverage is because it wasn’t widespread enough. Reported protests occurred in only 16 states and even those did not involve the entire inmate populations.

Strikers in Alabama, for example, were among the strike’s major organizers in the beginning, but they appeared to back down—for reasons that are still unclear.

Graeme Crews, communications associate at the Southern Poverty Law Center, told The Crime Report two main organizers of past strikes in Alabama have been in segregation.

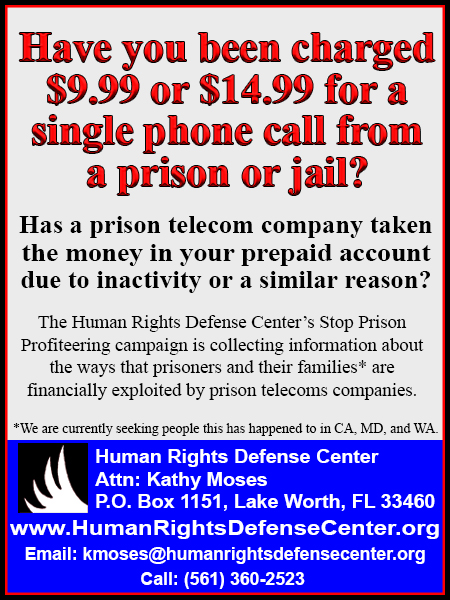

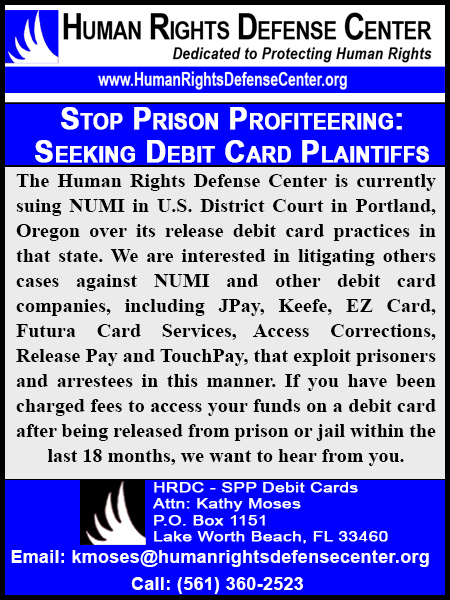

Paul Wright, executive director of the Human Rights Defense Center and editor of Prison Legal News said that prison is an intimidating place for Alabama inmates and their families were concerned.

“The reality is the prison officials that run these systems, they run their system by violence,” Wright told The Crime Report. “They’re petty, they’re vindictive, there’s no oversight.

“They can and do retaliate against people, usually for the pettiest and most trivial of reasons, and it’s not like anyone’s going to stop them.”

It’s not clear how many states participated in the strike, and even reported events are being questioned. Vicky Waters, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s press secretary, rejected reported claims that a 26-year-old inmate named Heriberto Garcia went on a hunger strike in Folsom State Prison.

“There were no protests or inmates on strike,” Waters said. “Some misinformation has been reported, but we did not have any hunger strikes, work stoppages, or any participation from inmates across our state prisons.”

Reports, however, suggests that inmates in San Quentin protested with the support of family and allies who stood on the outside, marching and chanting.

Willingham says the attention the strike received shouldn’t have been predicated on the size of the strike, or how many incarcerated people were involved.

“The people who were striking are enough for people to pay attention,” she said. “These are human beings, and they’re fed up.”

The national prison strike was sparked by a deadly riot that killed seven inmates in Lee Correctional Institution in April, and wounded over a dozen more. With the help of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee—a part of the Industrial Workers of the World—strikers published a lists of demands that included the right to vote and immediate improved prison conditions and policies.

“It’s not like what they’re asking for is unreasonable,” Willingham said. “These are basic human rights.”

The U.S. has the world’s largest prison population with 2.3 million people behind bars.