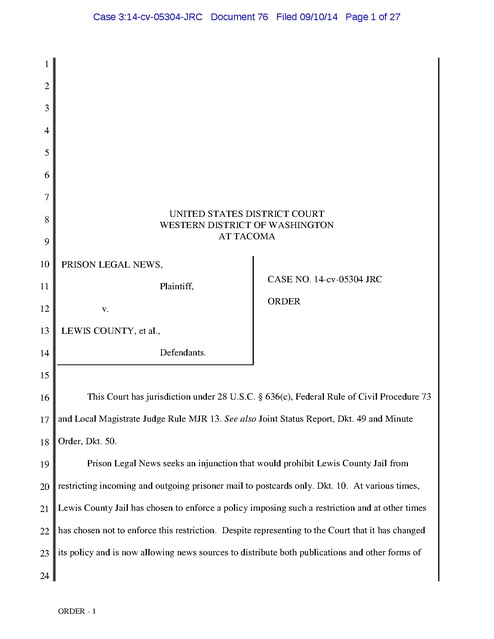

PLN v. Lewis Co., et al., WA, Order, censorship, 2014

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 1 of 27 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON AT TACOMA 8 9 10 PRISON LEGAL NEWS, 11 Plaintiff, 13 ORDER v. 12 CASE NO. 14-cv-05304 JRC LEWIS COUNTY, et al., Defendants. 14 15 16 This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 636(c), Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 73 17 and Local Magistrate Judge Rule MJR 13. See also Joint Status Report, Dkt. 49 and Minute 18 Order, Dkt. 50. 19 Prison Legal News seeks an injunction that would prohibit Lewis County Jail from 20 restricting incoming and outgoing prisoner mail to postcards only. Dkt. 10. At various times, 21 Lewis County Jail has chosen to enforce a policy imposing such a restriction and at other times 22 has chosen not to enforce this restriction. Despite representing to the Court that it has changed 23 its policy and is now allowing news sources to distribute both publications and other forms of 24 ORDER - 1 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 2 of 27 1 correspondence to prisoners, there is substantial evidence to believe that this policy has not yet 2 been adopted. 3 First Amendment rights are too important to be subject to such arbitrariness. When it 4 comes to access to news and information, prisoners and those who correspond with them should 5 be afforded the opportunity to send and receive mail, and if mail is refused by the Jail, prisoners 6 and persons attempting to communicate with prisoners should receive notice and a fair and 7 timely process for appealing the Jail’s refusal to deliver the mail. 8 Therefore, this Court GRANTS plaintiff’s motion for a preliminary injunction, as will be 9 further delineated below. 10 11 BACKGROUND 12 Plaintiff Prison Legal News (“PLN”) is published by the Human Rights Defense Center 13 (“HRDC”), a Washington Non-Profit Corporation. Dkt. 1 at ¶3.1. HRDC’s mission is public 14 education, prisoner education, advocacy, and outreach in support of the rights of prisoners and in 15 furtherance of basic human rights. Id. PLN publishes and distributes a monthly journal of 16 corrections news and analysis, as well as books about the criminal justice system and legal issues 17 affecting prisoners, to prisoners, lawyers, courts, libraries, and the public throughout the country. 18 Id. 19 From September 2013 through October 2013, PLN mailed to prisoners of Lewis County 20 Jail personally addressed envelopes containing informational brochures about subscribing to 21 PLN, copies of a catalog of books that PLN offers for sale, detailed book offers, and court 22 opinions. Dkt. 12 at ¶¶10-13, Exhibits A through SS (censored mail), Exhibits TT and UU 23 (exemplars). The Jail rejected and returned the mail, totaling forty-five pieces of mail. Dkt. 12 at 24 ORDER - 2 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 3 of 27 1 ¶¶12-13, Exhibits A through SS. On forty of the returned items, the Jail staff stamped “RETURN 2 TO SENDER This facility accepts postcards only.” Dkt. 12 at ¶¶ 12-13, Exhibits E through RR. 3 On three items Jail staff stamped “Returned to Sender REASON CHECKED BELOW” with 4 “Unauthorized Mail” checked or circled. Dkt. 12 at ¶¶ 12-13, Exhibits B through D. On two of 5 the items, Jail staff stamped both “RETURN TO SENDER This facility accepts postcards only” 6 and “Returned to Sender REASON CHECKED BELOW” with “Unauthorized Mail” circled; 7 and, on one of these double stamped items, Jail staff additionally stamped “RETURN TO 8 SENDER. UNDELIVERABLE AS ADDRESSED.” Dkt. 12 at ¶¶ 12-13, Exhibits A and SS. The 9 Jail also has rejected materials printed from PLN’s website that were sent to a prisoner by a 10 family member, such as one rejected in May, 2014. Dkt. 33 at ¶ 5, Exhibit B. The Jail rejects 11 mail sent from family members and friends if not in postcard form. Dkt. 34, Exhibits 1-3. 12 Defendants indicate that the Jail adopted its official mail policy on February 3, 2010, and 13 has officially adopted revisions as late as September 4, 2012. Dkt. 24, Exhibit 2. This policy 14 restricts all ingoing and outgoing prisoner personal mail to postcards only. Id. at page 2. The 15 policy also contains a “Publications” section that allows for the delivery of incoming soft 16 covered magazines. Id. at page 3. The Jail has also presented a draft policy that it claims to have 17 put into practice on June 2, 2014. Dkt. 71 at ¶ 2. This draft policy contains a separate section 18 regarding publishers and publications providing that correspondence between publishers and 19 prisoners will not be censored under the postcard-only policy. Dkt. 44, Exhibit 2 at page 2. 20 Despite this assertion, defendants admit that this draft policy has not been widely disseminated 21 nor officially adopted by the Jail. Dkt. 71 at ¶ 2; Dkt. 61, Exhibit 15 at page 18. The official 22 policy of the Jail remains the policy discussed above that was adopted February 3, 2010 and 23 revised as late as September 4, 2012. Dkt. 61, Exhibit 15 at page 18. Although this official policy 24 ORDER - 3 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 4 of 27 1 contains a subsection under the section titled “Incoming Mail” that allows for the delivery of 2 incoming soft covered magazines, it does not specifically address general correspondence 3 between publishers and prisoners in any other form. Dkt. 24, Exhibit 2 at page 3. On its face, the 4 correspondence PLN claims was wrongfully censored by defendants does not qualify under the 5 publications subsection of the Jail’s official policy and is therefore subject to the postcard-only 6 restriction applied to all personal mail. Id. at page 2-3. 7 8 PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND Plaintiff filed a Complaint on April 11, 2014, alleging that Lewis County Jail’s post-card 9 only rule violated PLN’s and prisoner-addressees’ protected free speech rights, as well as the 10 free speech rights of others who correspond with, or attempt to correspond with, prisoners. Dkt. 11 1 at ¶¶4.13, 4.14, 4.36-4.39, 5.2. Plaintiff also alleges that when defendants rejected mail based 12 on this post-card-only policy, Lewis County Jail failed to provide due process notice and 13 opportunity for appeal to PLN and other senders and receivers of the rejected prison mail. Dkt. 1 14 at ¶¶4.18-4.21, 4.40-4.41, 5.6. 15 Plaintiff filed a motion for preliminary injunction on April 21, 2014, requesting that this 16 Court enjoin the postcard-only rule and require notice and opportunity to be heard when mail is 17 rejected. Dkt. 10. That matter is currently before the Court. 18 19 DISCUSSION Standing. As a preliminary matter, plaintiff seeks to assert the First Amendment free 20 speech rights and Fourteenth Amendment due process rights not only on its own behalf, but also 21 on behalf of prisoners and other persons who send and receive mail to and from prisoners in the 22 Jail. Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 4.13, 4.16, 4.18, 4.19, 4.36-4.41, 5.2, 5.6; Dkt. 10 at page 2. 23 24 ORDER - 4 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 5 of 27 1 To satisfy standing requirements, a plaintiff must show: (1) that it has suffered an “injury 2 in fact” that is “(a) concrete and particularized and (b) ‘actual or imminent, not ‘conjectural’ or 3 ‘hypothetical;’’” (2) that the injury is fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant; 4 and (3) that it is “‘likely’, as opposed to merely ‘speculative’, that the injury will be ‘redressed 5 by a favorable decision.’” See Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555, 560–561 (1992) 6 (footnote and all citations omitted). 7 PLN has met each of these requirements. First, PLN has shown that the jail actually 8 rejected mail sent by plaintiff to prisoners, and has set forth concrete and particularized examples 9 of those rejections. Second, the action is fairly traceable to the Jail’s postcard-only policy as the 10 policy was in place at the time PLN’s mail was rejected and was used as the basis for rejecting 11 this mail. And, third, as will be discussed below, plaintiff has demonstrated that further injury 12 will be redressed by a favorable decision on the merits. Although defendants assert that its 13 postcard-only policy is no longer enforced, the policy remains in place and could be used again 14 to reject mail if it chose to enforce the policy. Therefore, this Court concludes that plaintiff has 15 standing to bring this motion for preliminary injunction on its own behalf. See id. 16 Further, plaintiff has standing to assert the rights of third parties who are not before the 17 Court. Under the overbreadth doctrine, a plaintiff “may challenge an overly broad statute or 18 regulation by showing that it may inhibit the First Amendment rights of individuals who are not 19 before the court.” 4805 Convoy, Inc. v. City of San Diego, 183 F.3d 1108, 1112 (9th Cir. 1999) 20 (citations omitted). The requirements to satisfy overbreadth standing are injury-in-fact and the 21 ability to frame the issues in the case satisfactorily. Id. (citing Secretary of Maryland v. Joseph 22 H. Munson Co., 467 U.S. 947, 958 (1984)). 23 24 ORDER - 5 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 6 of 27 1 First, the current official policy threatens the ability of those other than PLN to send 2 information packs and other non postcard materials to prisoners while also failing to provide 3 notice of the opportunity to appeal; and, such restriction has occurred, for instance, to a partner 4 of a prisoner who shares a child with the prisoner (see Dkt. 34 at Exhibits 1 and 3) as well as to a 5 mother of a prisoner (see Dkt. 34 at Exhibits 2 and 3). Thus, those other than PLN have been 6 injured-in-fact. 7 Second, PLN is certainly able to frame the issues on behalf of prisoners and other 8 correspondents. PLN has vigorously advocated on behalf of prisoners in previous litigation in 9 this Circuit. See, e.g., Prison Legal News v. Lehman, 397 F.3d 692 (9th Cir. 2005); Prison Legal 10 News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2001); Prison Legal News v. Columbia County, Dock. 11 No. 3:12-CV-00071-SI, 2012 WL 1936108, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 74030 (D. Or. May 29, 12 2012) (unpublished opinion); see also Dkt. 34. Furthermore, PLN has offered multiple 13 declarations from prisoners and their correspondents demonstrating that PLN has invested 14 significant time in determining how the Jail’s policy has affected prisoners and their 15 correspondents. See Dkt. 30; see also Dkt. 34. Finally, PLN has framed its argument to address 16 the allegedly overbroad nature of the mail policy’s postcard-only restriction and lack of 17 procedural due process safeguards while presenting specific alleged effects of the policy on 18 prisoners and their correspondents in addition to the effect on PLN alone. PLN has demonstrated 19 advocacy on behalf of prisoners and their other correspondents; and has demonstrated that it is 20 able to represent adequately prisoners and their correspondents’ interests in this litigation. 21 Therefore, PLN has standing to assert the rights of the prisoners and other potential senders and 22 recipients of prison mail. 23 24 ORDER - 6 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 7 of 27 1 While case law indicates that a free speech claim like plaintiff’s is an appropriate setting 2 for the application of the overbreadth doctrine, the doctrine does not appear to have been used by 3 other courts to cover claims such as plaintiff’s due process claims. The Supreme Court has 4 “recognized the validity of facial attacks alleging overbreadth (though not necessarily using that 5 term) in relatively few settings, and, generally, on the strength of specific reasons weighty 6 enough to overcome our well-founded reticence.” Sabri v. United States, 541 U.S. 600, 609-10 7 (2004) (citations omitted). Such settings include free speech, the right to travel, abortion, and 8 legislation under § 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. Id (citing Broadrick v. Oklahoma, 413 U.S. 9 601 (1973); Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964); Stenberg v. Carhart, 530 U.S. 10 914, 938–46 (2000); City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 532–35 (1997)) (other citations 11 omitted). The overbreadth doctrine should not be extended beyond these settings without good 12 reason. Sabri, supra, 541 U.S. at 610. Nonetheless, the Court finds that the same evidence 13 supports PLN’s ability to properly frame both First and Fourteenth Amendment interests of 14 prisoners and other correspondents. Additionally, PLN has indicated injury-in-fact arising from 15 the violation of both its First and Fourteenth Amendment rights. Therefore, the Court concludes 16 that the equal existence of these factors in regards to both constitutional rights, coupled with the 17 already appropriate application of the overbreadth doctrine to plaintiff’s free speech claim, 18 constitutes good reason for extending the doctrine to plaintiff’s Fourteenth Amendment due 19 process claims as well. Plaintiff may assert these claims on behalf of prisoners and other 20 correspondents whose mail is restricted by the Jail’s postcard-only policy. 21 Mootness. Also as a preliminary matter, defendants claim that the several instances cited 22 by plaintiff when its mail was rejected were isolated instances that were the result of one mail 23 handler’s misunderstanding and that these rejections will not likely happen again. Therefore, 24 ORDER - 7 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 8 of 27 1 according to defendants, this matter is moot and should not be the subject of a preliminary 2 injunction. “It is well settled that ‘a defendant’s voluntary cessation of a challenged practice 3 does not deprive a federal court of its power to determine the legality of the practice. . . . . If it 4 did, the courts would be compelled to leave ‘the defendant . . . . free to return to his old 5 ways.’’” Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Envtl. Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 189 6 (2000) (quoting City of Mesquite v. Aladdin’s Castle, Inc., 455 U.S. 283, 289, 289 n.10 (1982) 7 (citing United States v. W.T. Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629, 632 (1953))) (internal citations omitted). 8 A defendant claiming that its voluntary compliance moots a case bears the formidable 9 burden of showing that it is “absolutely clear the allegedly wrongful behavior could not 10 reasonably be expected to recur.” Friends of the Earth, supra, 528 U.S. at 189 (citing United 11 States v. Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., Inc., 393 U.S. 199, 203 (1968)). Accordingly, a 12 mere change in policy ante litem is not sufficient to moot a case unless it clearly shows that the 13 alleged wrong will not reasonably recur. 14 Defendants have not met this heavy burden. For instance, defendants acknowledge that 15 at the time of the incident, the Jail’s policy had a postcard-only policy, but argue that it chose not 16 to enforce it against PLN. Since PLN’s mail was rejected on several instances, it is clear that the 17 Jail’s policy of not following its policy does not negate a potential impact on PLN in the future. 18 Defendants also argue that the draft policy will cure the problem. But, for unknown 19 reasons, it has not yet been adopted. This fact, as well, leads the Court to conclude that it is not 20 “absolutely clear the allegedly wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected to recur.” 21 See Friends of the Earth, supra, 528 U.S. at 189 (citing Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., 22 Inc., supra, 393 U.S. at 203). 23 24 ORDER - 8 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 9 of 27 1 Furthermore, even the draft policy presented by the Jail is problematic. It includes a 2 “Publications/Other mail” section in addition to the categories of “Personal” and “Privileged” 3 mail. Dkt. 44, Exhibit 2. This newly drafted section suggests that “verifiable business, banks, 4 publishers, etc. shall not be subject to postcard rules,” but remains unclear about what 5 organizations actually qualify under this exception. Dkt. 45 at ¶ 5, Exhibit 2 at page 2. This is 6 particularly apparent where the next sentence of the same section offers a slightly expanded list 7 of correspondents who might qualify under the exception including publishers, “verifiable 8 business[es], government office[s], bank[s], book store[s], etc.” Id. (emphasis added). This draft 9 version of the new policy does far too little to alleviate concerns regarding the possibility that the 10 Jail will reject mail from PLN or other correspondents in the future, including correspondents 11 such as family and friends, whose rights are also being properly asserted by PLN, as noted 12 above. Furthermore, defendants’ assertion that the harm formerly done to PLN resulted from a 13 “misunderstanding” of the current policy only increases concerns that this vague new section 14 could be applied arbitrarily in the future. 15 Regarding PLN’s due process claims, the draft policy includes a statement that rejected 16 mail “will be returned to sender with a copy of the Notice of Withheld Material. The withheld 17 material notice shall include contact information and direction for due process,” and “[t]he 18 inmate . . . . will receive a copy of the Notice of Withheld Material.” Dkt. 45, Exhibit 2 at 19 page 3. PLN claims that these measures are still inadequate safeguards of its own due process 20 rights, the rights of prisoners, and the rights of other correspondents. The proposed policy does 21 not facially require notice of the reason for rejecting the mail by Jail staff. See id. And, it vaguely 22 addresses notice of an appeals process for those sending mail to prisoners, and neglects to 23 indicate if prisoners will be able to appeal the censorship of their mail by Jail staff. See id. 24 ORDER - 9 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 10 of 27 1 Furthermore, there is nothing in the policy that mentions notification or the right to appeal the 2 rejection of outgoing mail by Jail staff. See id. 3 Accordingly, several areas of dispute remain unresolved. Defendants have not satisfied 4 “the formidable burden of showing that it is absolutely clear the allegedly wrongful behavior 5 could not reasonably be expected to recur.” See Friends of the Earth, supra, 528 U.S. at 189 6 (citing Concentrated Phosphate Export Assn., Inc., 393 U.S. at 203). Therefore, this motion for 7 preliminary injunction is not moot. 8 Because plaintiff has standing to assert its rights and the rights of third parties, and 9 because this matter is not moot, the Court will now address the standards for granting a 10 preliminary injunction, as set forth in Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 11 (2008). Because plaintiff is seeking a preliminary injunction regarding both the Jail’s post-card 12 only policy and the Jail’s notice and appeals procedure for rejected mail, and those policies 13 potentially impact separate constitutionally protected rights, the Court will deal with each policy 14 separately. 15 Standards for preliminary injunction. A plaintiff seeking a preliminary injunction 16 must clearly establish: (1) that plaintiff is likely to succeed on the merits, (2) that plaintiff is 17 likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, (3) that the balance of 18 equities tips in plaintiff’s favor, and (4) that the injunction is in the public interest. Winter v. 19 Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008) (citations omitted); Fed. R. Civ. P. 65(a); 20 cf. M.R. v. Dreyfus, 663 F.3d 1100, 1108 (9th Cir. 2011) (the Court may grant a preliminary 21 injunction “if there is a likelihood of irreparable injury to the plaintiff; there are serious questions 22 going to the merits; the balance of hardships tips sharply in favor of the plaintiff; and the 23 24 ORDER - 10 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 11 of 27 1 injunction is in the public interest”); The Lands Council v. McNair, 537 F.3d 981, 987 (9th Cir. 2 2008), overturned by Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 22. 3 1. The Jail’s postcard-only policy. The Jail’s policy regarding personal mail states, 4 in part, “Incoming and outgoing personal mail shall be postcard media only.” Dkt. 24, Exhibit 2 5 at page 2. PLN alleges that defendants violated its free speech rights and those of other 6 publishers and correspondents by limiting prisoner personal mail to postcards only and by 7 rejecting informational brochure packs and court opinions that PLN mailed to prisoners in 8 envelopes. Dkt. 1 at ¶¶ 4.13-4.14, 4.26-4.27, 4.33. The Jail’s policy provides an exception for 9 “Publications” as follows: “Publications are allowed for inmates. Publications must come 10 directly from a publisher or approved book store and must be soft covered. Publications must be 11 individually addressed.” Dkt. 24, Exhibit 2 at page 3. The policy does not define a 12 “publication,” but it is clear that it was not interpreted by the Jail to include the informational 13 brochure packets that plaintiff sent to prisoners and were rejected. 14 Under the first factor of the test in Winter, plaintiff has the burden of demonstrating that 15 it is likely to succeed on the merits. See Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20. Prisoners and their 16 correspondents have a First Amendment interest in sending each other mail. The Ninth Circuit 17 has “repeatedly recognized that publishers and inmates have a First Amendment interest in 18 communicating with each other.” Hrdlicka v. Reniff, 631 F.3d 1044, 1049 (9th Cir. 2010) (citing 19 Prison Legal News v. Lehman, 397 F.3d 692, 699 (9th Cir. 2005); Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 20 U.S. 401, 408 (1989)). Also, prison and jail walls do not “bar free citizens from exercising their 21 own constitutional rights by reaching out to those on the ‘inside.’” Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 22 U.S. 401, 407 (1989) (citing Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 94-99 (1987); Bell v. Wolfish, 441 23 24 ORDER - 11 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 12 of 27 1 U.S. 520 (1979); Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc., 433 U.S. 119 (1977); 2 Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974)) (internal citation omitted). 3 This First Amendment interest extends to receiving mail as well as sending it. “It is now 4 well established that the Constitution protects the right to receive information and ideas. ‘This 5 freedom [of speech and press] . . . . necessarily protects the right to receive . . . . ’” Stanley 6 v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557, 564 (1969) (citing Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 U.S. 141, 143 7 (1943); Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 482 (1965); Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 8 U.S. 301, 307-08 (1965) (Brennan, J., concurring); cf. Pierce v. Society of the Sisters, 268 U.S. 9 510 (1925)). Accordingly, plaintiff has a First Amendment interest in both sending 10 correspondence to prisoners and receiving correspondence in return. Additionally, prisoners and 11 their other correspondents share the same constitutional interest. 12 Notwithstanding the implication of a First Amendment interest, “restrictions that are 13 asserted to inhibit First Amendment interests must be analyzed in terms of the legitimate policies 14 and goals of the corrections system . . . .” Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817, 822 (1974). In 15 Turner v. Safley, the Supreme Court determined that when prison regulations impinge on 16 constitutional interests, the regulations are valid if “reasonably related to legitimate penological 17 interests.” 482 U.S. 78, 89 (1987), superceded by statute, 42 U.S.C. § 2000cc-1(a)(1)-(2), with 18 respect to burdens on religious exercise, as stated in Warsoldier v. Woodford, 418 F.3d 989, 994 19 (9th Cir. 2005) (citation and footnote omitted). The Court provided a four-factor test to evaluate 20 “the reasonableness of a prison or jail regulation impinging on a constitutional right.” Hrdlicka, 21 supra, 631 F.3d at 1049. This test considers: 22 23 (1) whether the regulation is rationally related to a legitimate and neutral governmental objective, (2) whether there are alternative avenues that remain open to the inmates to exercise the right, (3) the impact that accommodating the asserted right will have on other guards and prisoners, and on the allocation of 24 ORDER - 12 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 13 of 27 1 prison resources; and (4) whether the existence of easy and obvious alternatives indicates that the regulation is an exaggerated response by prison officials. 2 Prison Legal News v. Lehman, 272 F.Supp. 2d 1151, 1155 (W.D. Wash. 2003) (quoting Prison 3 Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145, 1149 (9th Cir. 2001) (citing Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 894 90)). Not only do these factors apply in evaluating regulations that govern prisoners’ right to 5 receive mail, but they also apply to regulations affecting correspondents’ “rights to send 6 materials to prisoners.” Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145, 1149 (9th Cir. 2001) (citing 7 Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. at 413). 8 The first Turner factor requires this Court to determine if the postcard-only policy is 9 rationally related to a legitimate and neutral governmental objective. See Turner, supra, 482 U.S. 10 at 89-90 (citations omitted). Defendants assert that the postcard-only policy is aimed at 11 improving jail security by reducing the importation of contraband, the amount of resources spent 12 screening mail, and prisoner misuse of the mailing system. Dkt. 25 at ¶¶ 3, 4. Prison security is 13 undeniably a legitimate penological objective. See Thornburg, supra, 490 U.S. at 415. The 14 policy also is neutral because it draws a distinction between postcards and other forms of mail 15 “solely on the basis of their potential implications for prison security . . . .” Id. (footnote 16 omitted). 17 The burden of showing a rational relationship lies with defendants, and is initially 18 satisfied by presenting an “intuitive, common-sense connection” between the objective and the 19 regulation. Frost v. Symington, 197 F.3d 348, 354, 356-57 (9th Cir. 1999). If PLN is able to 20 show sufficient evidence refuting the connection, defendants must additionally present enough 21 evidence “to show that the connection is not so ‘remote as to render the policy arbitrary or 22 irrational.’” Id. (quoting Mauro v. Arpaio, 188 F 3.d 1054, 1060 (9th Cir. 1999) (quoting Turner, 23 supra, 428 U.S. at 89-90 and Amatel v. Reno, 156 F.3d 192, 200-01 (D.C. Cir. 1998))). 24 ORDER - 13 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 14 of 27 1 Here, defendants indicate that “[i]t is simply more effective to visually scan a postcard 2 for contraband and other issues than it is to scan a closed envelope, remove its contents, and 3 review the same for all of the issues of which our staff has to be aware . . . . ” Dkt. 25 at ¶ 10. 4 Such issues include concerns about materials like anthrax, weapons, secreted drugs, coded 5 messages, or even bodily fluids being sent through the mail. Id. at ¶¶ 2, 3. Additionally, 6 defendants indicate that the postcard-only policy reduces the time that staff spends screening 7 mail by half. Id. at ¶ 4. This showing sufficiently establishes a common-sense connection 8 between the postcard-only policy and the asserted objective. This factor weighs in favor of 9 defendants. 10 The second Turner factor considers whether or not “‘other avenues’ remain available for 11 the exercise of the asserted right.” Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 90 (citations omitted). In 12 evaluating this factor, alternative means need not be ideal, but they must be reasonably available. 13 See Overton v. Bazzetta, 539 U.S. 126, 135 (2003). Nonetheless, “‘the right’ in question must be 14 viewed sensibly and expansively.” Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. at 417 (citing Turner, supra, 15 482 U.S. 78; O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342 (1987)). Defendants contend that 16 alternate avenues exist to exercise free speech rights because other channels remain open for 17 contacting prisoners, like sending emails, making phone calls, or utilizing regular visitation. See 18 Dkt. 45 at ¶¶ 9, 11. 19 On this point, the facts indicate otherwise. The postcard-only policy, on its face, prevents 20 PLN from sending materials that are not easily transferable to a postcard, such as court opinions 21 and informational packets. PLN has shown that the information included in these mailings 22 cannot be formatted to fit onto a postcard. Dkt. 12 at ¶ 17, Exhibits TT, UU. For this reason and 23 24 ORDER - 14 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 15 of 27 1 due to PLN’s necessary reliance on such materials to secure new subscribers and its continued 2 vitality, the barriers implicated by the policy are not an insubstantial hardship. See id. 3 The policy also prevents family members from sending items like photographs, copies of 4 bills, and medical information. See, e.g., Dkt. 34. None of these things can be easily replaced by 5 telephone calls or regular visitation. It has been recognized that such communication with 6 family and friends “advances rather than retards the goal of rehabilitation . . . .” Procunier v. 7 Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 412-13 (1974) (quoting Policy Statement 7300.1A of the Federal Bureau 8 of Prisons (the policy “recognized that any need for restrictions arises primarily from 9 considerations of order and security rather than rehabilitation: ‘Constructive, wholesome contact 10 with the community is a valuable therapeutic tool in the overall corrections process’”); Policy 11 Guideline of the Association of State Correctional Administrators of August 23, 1972 (the policy 12 guideline “echoes the view that personal correspondence by prison inmates is a generally 13 wholesome activity: ‘Correspondence with members of an inmate’s family, close friends, 14 associates and organizations is beneficial to the morale of all confined persons and may form the 15 basis for good adjustment in the institution and the community’”)) (footnote omitted), overruled 16 on other grounds, Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401, 407, 413-16, 419 (1989) (noting the 17 “undoubtedly” legitimate claim to prison access by “families and friends of prisoners who seek 18 to sustain relationships with them”) (citations omitted). 19 The postcard-only policy drastically reduces prisoners’ and other correspondents’ ability 20 to communicate. It is more than a mere inconvenience and becomes a substantial barrier to First 21 Amendment rights. Incarceration does not “form a barrier separating prison inmates [or free 22 citizens] from the protections of the Constitution . . . . ” Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. at 407 23 (citing Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 84, 94-99; Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520 (1979); Jones v. North 24 ORDER - 15 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 16 of 27 1 Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc., 433 U.S. 119 (1977); Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 2 (1974)). Accordingly, the second Turner factor favors PLN as “‘the right’ in question must be 3 viewed sensibly and expansively.” Id. at 417 (citing Turner, supra, 482 U.S. 78; O’Lone, supra, 4 482 U.S. 342). 5 The third Turner factor considers the impact that “accommodation of the asserted 6 constitutional right will have on guards and other inmates, and on the allocation of prison 7 resources generally.” Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 90. Because of the high likelihood that even the 8 smallest changes will have some “ramification of the liberty of others or on the use of the 9 prison’s limited resources[,]” this third factor weighs most heavily when “accommodation of an 10 asserted right will have a significant ‘ripple effect’ on fellow inmates or on prison staff.” Id. 11 Also, “the policies followed at other well-run institutions [are] relevant to a determination of the 12 need for a particular type of restriction.” Martinez, supra, 416 U.S. at 414 n.14, overruled on 13 other grounds, Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. 401; see also Morrison v. Hall, 261 F.3d 896, 905 14 (9th Cir. 2001) (citing Martinez, supra, 416 U.S. at 414 n.14, overruled on other grounds, 15 Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S 401). 16 Defendants state that the postcard-only policy reduces by half the time that staff members 17 spend screening mail, but PLN aptly raises important questions concerning the actual amount of 18 time that is saved. Compare Dkt. 25 at ¶ 4 with Dkt. 34 at ¶¶ 11-12. PLN questions the methods 19 by which this figure was obtained. Dkt. 34 at ¶¶ 11-12. Also, PLN contends that the time 20 necessary to review the mailing, mark the reason for its rejection, and attach a notice regarding 21 an option to appeal the decision arguably would be no greater than the time necessary to open 22 and inspect the contents of the envelope for contraband and send it on to the intended recipient. 23 Defendants’ assertion regarding the impact on its budget is simply not well documented nor 24 ORDER - 16 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 17 of 27 1 supported by substantial quantitative and qualitative evidence. Instead, it seems to be based 2 entirely on conjecture, rather than analysis and evidence. Therefore, without more, this Court 3 cannot ascribe substantial weight to this assertion. Accordingly, the third Turner factor supports 4 PLN’s argument because defendants have failed to demonstrate that accommodating these First 5 Amendment rights will have a significant impact on other guards and prisoners or on the 6 allocation of prison resources. 7 In addition, PLN also has identified numerous prison and jail systems that do not enforce 8 a postcard-only policy, but instead perform mail inspections, as Lewis County Jail has done in 9 the past. Such systems include the Washington Department of Corrections (“WDOC”), the 10 Bureau of Prisons, King County Jail, Pierce County Jail, and Spokane County Jail. Dkt. 10 at 11 page 18. In contrast, defendants indirectly refer to two jail systems that likewise employ 12 postcard-only policies. See Dkt. 22 at pages 3, 10-11. However, the prevalence of the alternative 13 policies allowing for enveloped mail among “well-run institutions” suggests that postcard-only 14 policies do not increase efficiency enough to result in their widespread adoption. 15 The final Turner factor addresses if “the existence of easy and obvious alternatives 16 indicates that the regulation is an exaggerated response by prison officials.” Cook, supra, 238 17 F.3d at 1149 (citing Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 89-90). This factor should not be mistaken for a 18 least restrictive alternative analysis; prisons need not always adopt the least restrictive 19 alternative. See Turner, supra, 482 U.S. at 90-91 (citations omitted). However, courts may 20 consider “an alternative that fully accommodates the [asserted] rights at de minimis cost to valid 21 penological interests” as evidence that the policy unreasonably infringes upon First Amendment 22 rights. Id. at 91. 23 24 ORDER - 17 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 18 of 27 1 As discussed above, PLN has indicated that simply opening and inspecting enveloped 2 mail is a ready alternative to Lewis County Jail’s postcard-only policy. This was the policy 3 employed previously by Lewis County Jail and the Jail has reported no incidents of misconduct 4 where the resulting danger would have increased had the jail allowed envelopes and letters. Also, 5 defendants have failed to show that inspecting enveloped letters instead of outright rejecting 6 them will be difficult or will result in an undue burden on administrative costs. The fact that 7 systems like the Bureau of Prisons, the WDOC, and large county jails in the immediate region all 8 accommodate enveloped mail without compromised security evidences that the postcard-only 9 policy is an exaggerated response to the potential dangers that accompany the postal service. 10 Dkt. 10 at 18; see Morrison, supra, 261 F.3d at 905 (finding that alternative “policies followed at 11 other well-run institutions” evidenced that easy and obvious alternatives existed to the 12 challenged regulation) (citations omitted). In light of these other institutions’, and Lewis County 13 Jail’s own successful past use of a letter inspecting policy, the fourth factor suggests that the 14 postcard-only policy is an exaggerated response by prison officials, thus weighing in favor of 15 PLN’s position. 16 In summary, although defendants succeed in stating a “rational” relationship between the 17 postcard-only policy and legitimate penological interests, the remaining Turner factors weigh 18 heavily in favor of PLN. This “rational” relationship is insufficient to justify such a substantial 19 barrier on First Amendment rights. Therefore, plaintiff has demonstrated that it likely will 20 succeed on the merits of its First Amendment claims, satisfying the first prong of the Winter test. 21 See Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20. 22 Under the second prong in Winter, plaintiff has the burden of proving that it is likely to 23 suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief. Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20. To 24 ORDER - 18 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 19 of 27 1 meet this burden, it is well recognized that “[t]he loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even 2 minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.” Elrods v. Burns, 427 3 U.S. 347, 373 (1976) (citing New York Times Co. v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) (footnote 4 omitted)); see also Klein v. City of San Clemente, 584 F.3d 1196, 1207-08 (9th Cir. 2009). 5 However, the fact of past injury, while presumably affording a plaintiff standing to claim 6 damages, “does nothing to establish a real and immediate threat that he would again” suffer 7 similar injury in the future. City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95, 105 (1983). 8 As discussed above, see supra, Mootness section, the proposed change in the Jail’s policy 9 does too little to alleviate the Court’s concerns regarding the possibility that the Jail will reject 10 mail from PLN or other correspondents in the future. Due to the vagueness of the policy in 11 regards to who qualifies as a “publisher/other,” the policy on its face could be applied differently 12 to nearly identical organizations resulting in the arbitrary denial of plaintiff’s right to free speech. 13 Additionally, other personal mail remains restricted to postcards only, preventing 14 communications between prisoners and family or other correspondents. Therefore, this Court 15 concludes that the Jail’s postcard-only policy is likely to cause further irreparable injury in the 16 future. 17 The third Winter test, that the balance of equities tips in plaintiff’s favor, is very similar 18 in application to the weighing of interests that the Court already has conducted under Turner. 19 Compare Winter v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., supra, 555 U.S. 20 with Turner v. Safley, 20 supra, 482 U.S. at 89-91. Therefore, the Court simply notes here that analysis of the postcard21 only policy under the Turner factors establishes that the balance of equities tips in favor of 22 plaintiff. Considering that the Jail previously has allowed enveloped mail, and due to a lack of 23 evidence showing that a return to this policy would cause inordinate harm or difficulty, the Court 24 ORDER - 19 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 20 of 27 1 concludes that the Jail’s postcard-only policy cannot justify the dramatic impact on plaintiff’s, 2 prisoners’, and other correspondents’ First Amendment rights. 3 The final test under Winter is whether or not the injunction is in the public interest. 4 Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20. “The public interest primarily addresses [the] impact on non5 parties rather than parties.” Sammartano v. First Judicial Dist. Court, in & for County of Carson 6 City, 303 F.3d 959, 974 (9th Cir. 2002), overruled on other grounds, Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 7 22. Here, an injunction would not only benefit PLN, but it also would directly benefit other 8 publishers similarly situated as well as other members of the public who wish to communicate 9 with prisoners through written correspondence. Additionally, because communication with 10 family and friends “advances rather than retards the goal of rehabilitation,” such an injunction 11 would benefit the public generally. Martinez, supra, 416 U.S. at 412-13 (footnote and quotations 12 omitted), overruled on other grounds, Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. at 407 (noting the 13 “undoubtedly” legitimate claim to prison access by “families and friends of prisoners who seek 14 to sustain relationships with them”) (citations omitted). 15 In summary, plaintiff has satisfied each of the prongs set forth in Winter, and is therefore 16 entitled to an injunction regarding the postcard-only policy. The Court still needs to address the 17 form of such an injunction. Plaintiff proposes that this Court order a mandatory injunction. “‘A 18 mandatory injunction orders a responsible party to take action,’ while ‘[a] prohibitory injunction 19 prohibits a party from taking action and preserves the status quo pending a determination of the 20 action on the merits.’” Arizona Dream Act Coal. v. Brewer, 757 F.3d 1053, 2014 U.S. App. 21 LEXIS 12746 at *13-*14 (9th Cir. 2014) (citing Marlyn Nutraceuticals, Inc. v. Mucos Pharma 22 GmbH & Co., 571 F.3d 873, 878–79 (9th Cir. 2009) (internal quotation marks and alteration 23 omitted), overruled on other grounds, Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 22; see also Flexible Lifeline 24 ORDER - 20 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 21 of 27 1 Sys., Inc. v. Precision Lift, Inc., 654 F.3d 989, 997-98 (9th Cir. 2011)). In the context of an 2 injunction, “the ‘status quo’ refers to the legally relevant relationship between the parties before 3 the controversy arose.” Id. at *13 (citing McCormack v. Hiedeman, 694 F.3d 1004, 1020 (9th 4 Cir. 2012)). Policy changes in response to litigation are an affirmative change of the status quo. 5 See id. (“By revising their policy in response to DACA, Defendants affirmatively changed this 6 status quo. The district court erred in defining the status quo ante litem . . . . ”). 7 The Court has been provided several options by the parties. Rather than delineating all 8 aspects of a mail policy, the most straight forward approach is simply to prohibit that which is 9 unconstitutional. Therefore, the Court preliminarily enjoins defendants from restricting 10 incoming and outgoing prisoner mail to postcards only, and orders defendants not to refuse to 11 deliver or process prisoner personal mail on the ground that it is in a form other than a postcard. 12 Any policy or practice that does not conform with this restriction is enjoined during the 13 pendency of this action or until further order of this Court. 14 2. 15 Plaintiff further alleges that by rejecting mail without providing information regarding a The Jail’s notice and appeals procedure for rejected mail. 16 right to appeal, defendants violated plaintiff’s, prisoners’, and other correspondents’ Fourteenth 17 Amendment rights to due process. Dkt. 1 at ¶5.6. Plaintiff seeks to obtain an injunction 18 delineating the due process procedure to be followed by defendants during the pendency of these 19 proceedings. Dkt. 10 at pages 20 – 24. 20 In order to protect the Fourteenth Amendment rights of prisoners and their 21 correspondents, “the decision to censor or withhold delivery of a particular letter must be 22 accompanied by minimum procedural safeguards.” Martinez, supra, 416 U.S. at 417, overruled 23 on other grounds, Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401 (1989). Inmates have “a Fourteenth 24 ORDER - 21 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 22 of 27 1 Amendment due process liberty interest in receiving notice that [their] incoming mail is being 2 withheld by prison authorities.” Frost v. Symington, 197 F.3d 348, 353 (9th Cir. 1999) (citations 3 omitted). 4 A preliminary injunction regarding the Jail’s notice and appeals procedures will be 5 granted if plaintiff in the due process context satisfies the four part test set forth in Winter v. 6 Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 555 U.S. 7, 20 (2008). Therefore, the following discussion sets 7 forth this Court’s analysis of those factors as they relate to plaintiff’s Fourteenth Amendment due 8 process claim. 9 Under the first prong of Winter, plaintiff has the burden of demonstrating that plaintiff is 10 likely to succeed on the merits. See Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20. It is axiomatic that due 11 process is adversely impacted by vague policies or disparate enforcement of those policies. See, 12 e.g., Giaccio v. Pennsylvania, 382 U.S. 399, 402 (1966) (“the 1860 Act is invalid under the Due 13 Process Clause because of vagueness and the absence of any standards sufficient to enable 14 defendants to protect themselves against arbitrary and discriminatory impositions of costs . . . . 15 Certainly one of the basic purposes of the Due Process Clause has always been to protect a 16 person against having the Government impose burdens upon him except in accordance with the 17 valid laws of the land. Implicit in this constitutional safeguard is the premise that the law must be 18 one that carries an understandable meaning with legal standards that courts must enforce”). And, 19 it is problematic that the Jail’s notice and appeal procedure is unclear. 20 A policy is set forth in POL 05.07.050, which states in part: 21 The Administrative Lieutenant may authorize restrictions of incoming or outgoing mail when the correspondence is deemed to be a threat to the legitimate penological interest of the facility. The Administrative Lieutenant shall provide written notification to both inmate and sender identifying the reason for the restriction, and advise both of their right to request a review. Staff shall accept a 22 23 24 ORDER - 22 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 23 of 27 1 written request for review within ten days of initial notice. The Jail Administrator shall review the restriction and respond in a reasonable amount of time. . . . 2 Dkt. 12, Exhibit 2, Wright Declaration, Exhibit VV to Wright Declaration at page 3. 3 Plaintiff argues that defendants failed to comply with this policy, that the policy fails to 4 define “threat to the legitimate penological interest,” and that the policy is confusing and 5 provides no information regarding how to obtain the stated review. Dkt. 10 at pages 21-22. 6 Another mail policy indicates that prisoners and their correspondents must be notified of 7 the rejection by Jail staff of incoming mail, but that policy remains silent regarding outgoing 8 mail rejected by Jail staff. Dkt. 45, Exhibit 2 at page 3. It states that if incoming mail is rejected 9 for cause, it will be returned to the sender with a copy of the Notice of Withheld Material and 10 shall include contact information and directions for due process. See id. Copies of this notice 11 will be sent to the intended prisoner recipient. See id. The same procedure does not apply to 12 outgoing mail rejected by Jail staff and no appeals procedure for prisoners is set forth in the 13 policy. See id. 14 Defendants claim that the grievance policy contained in the Inmate Manual satisfies all of 15 plaintiff’s due process concerns. Dkt. 22 at page 11 (citing Dkt. 25, Exhibit 2). That Manual is 16 for prisoners only, and not for other non-prisoner correspondents. The Manual does not refer 17 specifically to the procedure that should be followed if mail is rejected, nor what notice is 18 required, although it indicates that prisoners will be provided a written explanation when 19 incoming mail (only) is rejected and instructs prisoners that they can appeal “to the 20 Administration Lieutenant through the kiosk (GT) system.” See Dkt. 25, Exhibit 2 at pp. 9-11. 21 Defendants have not clarified how this manual is applied to rejected mail and has not clarified 22 whether or not prisoners are given any notice of the Jail refusing to send their mail. See id. 23 24 ORDER - 23 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 24 of 27 1 Plaintiff argues that because of the disparate policies and procedures “the Jail’s mail staff 2 will be left to use unfettered discretion to apply the confusing and inconsistent policy according 3 to their own interpretations.” Dkt. 10 at p. 22. And, that appears to be exactly what occurred 4 here. The Jail applied different stamps, advising the senders of different objections to the same 5 types of mail. See Dkt. 12 at ¶¶ 12-13, Exhibits A through SS. None of the notices provided 6 information to plaintiff of the procedure for appealing the rejections. Id. And, plaintiff has 7 submitted evidence that prisoners were not given any notice that their mail had been rejected or 8 that mail from the outside was not getting in. See Dkt. 32, Exhibit 3 at page 4. This is simply 9 insufficient. 10 In Martinez, the Supreme Court affirmed an order by a district court that “required that an 11 inmate be notified of the rejection of a letter written by or addressed to him, that the author of 12 that letter be given a reasonable opportunity to protest that decision, and that complaints be 13 referred to a prison official other than the person who originally disapproved the 14 correspondence.” Martinez, supra, 416 U.S. at 418-19, overruled on other grounds, Thornburgh, 15 supra, 490 U.S. 401. Non-prisoner correspondents also have a constitutional interest in 16 communicating with prisoners. See id.; Thornburgh, supra, 490 U.S. at 407 (prison and jail walls 17 do not “bar free citizens from exercising their own constitutional rights by reaching out to those 18 on the ‘inside’”) (citations omitted). Therefore, plaintiff has satisfied this Court that the Jail’s 19 policies and practices of notifying senders and recipients of prison mail are unclear and 20 irregularly applied. As such, the Court finds that plaintiff is likely to prevail on this issue and 21 that the Jail’s policy as applied is unconstitutional. 22 As set forth previously, under the second prong in Winter, “an alleged constitutional 23 infringement will often alone constitute irreparable harm.” Monterey Mech. Co. v. Wilson, 125 24 ORDER - 24 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 25 of 27 1 F.3d 702, 715 (9th Cir. 1997) (quoting Associated General Contractors v. Coalition for 2 Economic Equity, 950 F.2d 1401, 1412 (9th Cir. 1991), overruled on other grounds, United Food 3 & Commercial Workers Union Local 751 v. Brown Group, Inc., 517 U.S. 544, 551 (1996) 4 (quoting Goldie’s Bookstore v. Superior Ct., 739 F.2d 466, 472 (9th Cir. 1984) (citing Wright & 5 Miller, 11 Federal Practice and Procedure § 2948 at 440 (1973))). Due process, as guaranteed by 6 the Fourteenth Amendment, cannot be protected by vague and irregularly applied policies and 7 procedures. The threat of this continuing harm sufficiently satisfies this element of the Winter 8 test. See Winter, supra, 555 U.S. at 20; see also Elrods, supra, 427 U.S. at 373 (citing New York 9 Times Co., supra, 403 U.S. 713 (footnote omitted)); Klein, supra, 584 F.3d at 1207-08. 10 Regarding the third prong in the Winter test, the Court concludes that the balance of 11 equities tips in plaintiff’s favor as to prisoners and those sending correspondences to prisoners. 12 Defendant has made no attempt to argue that it would be burdensome to provide sufficient notice 13 to prisoners. In fact, it argues that it is already doing so, despite plaintiff’s evidence to the 14 contrary. Nor have defendants argued that providing sufficient notice to persons whose mail is 15 rejected would be an unreasonable burden; instead arguing that they, too, receive this notice, 16 despite the evidence to the contrary. 17 However, defendants have articulated good reasons for not being required to notify 18 persons who do not receive rejected mail from prisoners. As to those persons, the Jail argues 19 persuasively that if a prisoner attempts to send a message that would violate a restraining order 20 or potentially lead to harmful actions taken by others, a requirement that the Jail notify the 21 intended recipient of the attempted contact would defeat the entire purpose of screening the 22 dangerous mail in the first place. See Dkt. 44 at ¶ 4.41. As to those persons, the Court agrees that 23 the balance of hardships does not tip in favor of plaintiff. Because it is difficult to determine 24 ORDER - 25 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 26 of 27 1 which potential non-prisoner recipients may benefit from notice, and because prisoners’ due 2 process rights can be adequately protected by providing them notice, the Court will not require 3 that the Jail inform the intended recipients that prisoners’ mail to them has been rejected. 4 Except as to those intended recipients of prisoners’ mail, under the forth Winter test, the 5 public interest is well served by requiring the Jail to provide notice and a clear appeals process to 6 prisoners of both rejected incoming and outgoing mail, as well as to non-prisoner correspondents 7 whose mail is rejected. 8 Rather than attempting to write jail policy, this Court will delineate the parameters of a 9 constitutionally acceptable policy. First, the Jail must notify a prisoner when it rejects 10 correspondence written by or addressed to the prisoner. This notification, at a minimum, will set 11 forth the reason the mail was rejected, and the procedure to follow if the prisoner wishes to 12 appeal the rejection. Second, the Jail must notify a non-prisoner correspondent if the non13 prisoner correspondent’s mail is rejected. Such notification, at a minimum, will set forth the 14 reason mail was rejected, and the procedure to follow if the non-prisoner correspondent wishes 15 to appeal the rejection. Third, any appeal of rejected mail will be referred to a jail official other 16 than the person who originally rejected the correspondence. 17 ACCORDINGLY, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that for the duration of plaintiff’s 18 lawsuit, the Court: 19 20 21 22 23 24 1. PRELIMINARILY ENJOINS defendants from restricting incoming and outgoing prisoner mail to postcards only, and orders defendants not to refuse to deliver or process prisoner personal mail on the grounds that it is in a form other than a postcard. 2. PRELIMINARILY ENJOINS defendants from rejecting mail to or from prisoners without providing notice to the prisoner. This notification, at a minimum, will set forth ORDER - 26 Case 3:14-cv-05304-JRC Document 76 Filed 09/10/14 Page 27 of 27 1 the reason the mail was rejected and the procedure to follow if the prisoner wishes to appeal the 2 rejection. 3 3. PRELIMINARILY ENJOINS defendants from rejecting mail from non- 4 prisoner correspondents without providing notice to the non-prisoner correspondent. This 5 notification, at a minimum, will set forth the reason the mail was rejected, and the procedure to 6 follow if the non-prisoner correspondent wishes to appeal the rejection. 7 4. PRELIMINARILY ENJOINS any appeal of rejected mail that is not referred to 8 a jail official other than the person who originally rejected the correspondence. 9 Dated this 10th day of September, 2014. 10 11 A 12 J. Richard Creatura United States Magistrate Judge 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 ORDER - 27