Prison Legal News v EOUSA, CO, Order releasing certain info, 2009

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

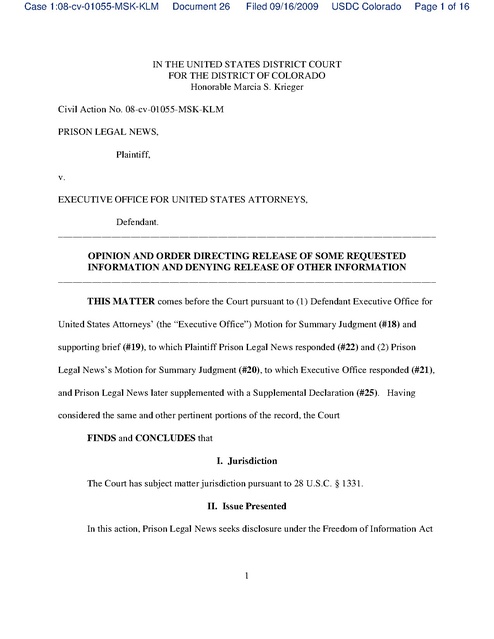

Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 16 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Honorable Marcia S. Krieger Civil Action No. 08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM PRISON LEGAL NEWS, Plaintiff, v. EXECUTIVE OFFICE FOR UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS, Defendant. ______________________________________________________________________________ OPINION AND ORDER DIRECTING RELEASE OF SOME REQUESTED INFORMATION AND DENYING RELEASE OF OTHER INFORMATION ______________________________________________________________________________ THIS MATTER comes before the Court pursuant to (1) Defendant Executive Office for United States Attorneys’ (the “Executive Office”) Motion for Summary Judgment (#18) and supporting brief (#19), to which Plaintiff Prison Legal News responded (#22) and (2) Prison Legal News’s Motion for Summary Judgment (#20), to which Executive Office responded (#21), and Prison Legal News later supplemented with a Supplemental Declaration (#25). Having considered the same and other pertinent portions of the record, the Court FINDS and CONCLUDES that I. Jurisdiction The Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1331. II. Issue Presented In this action, Prison Legal News seeks disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 1 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 16 (“FOIA”)1 of certain video and photographic records that were used in the prosecution of a federal death penalty case. The Executive Office maintains that the records are not subject to disclosure because they fall within two enumerated exemptions in FOIA. Therefore, the sole issue presented in this case is whether, as a matter of law, the records requested are properly withheld under an enumerated exemption in FOIA.2 III. Material Facts On October 10, 1999, William Sablan and Rudy Sablan murdered Joey Jesus Estrella in their shared prison cell at the United States Penitentiary in Florence, Colorado (“USPFlorence”). The Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”) videotaped William and Rudy Sablan’s actions after the murder, which tape displays William Sablan’s mutilation and handling of Mr. Estrella’s body and internal organs and his purported drinking of Mr. Estrella’s blood. Inevitably, the video also shows the numerous physical injuries that were inflicted on Mr. Estrella. The video also depicts the BOP’s removal of William and Rudy Sablan from the cell, their initial physical exams, and their placement in four-point restraints in separate cells. In separate trials, the government prosecuted William and Rudy Sablan for Mr. Estrella’s murder. See 00-cr-00531-WYD-1 (William Sablan); 00-cr-00531-WYD-2 (Rudy Sablan). During the trials, the video and autopsy photographs were introduced as evidence and played for the courtroom audience. After the trials, all exhibits were returned to the parties pursuant to 1 Particularly, 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). 2 Although the parties have submitted cross motions for summary judgment, the only issue presented to the Court is for a legal determination on the application of FOIA exemptions. No material facts are in dispute. Therefore, the Court construes the cross motions for summary judgment as motions for determination of legal issues on undisputed facts. 2 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 3 of 16 court policy and order by Judge Wiley Y. Daniel. The United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Colorado is currently in possession of the records at issue—the video and autopsy photographs. On March 12, 2007, Prison Legal News sent a FOIA request to the U.S. Attorney’s Office seeking disclosure of the video and the “still photographs of the body of” Mr. Estrella3 that were used in the trials. The Executive Office denied the request in full on May 15, 2007. Prison Legal News’s administrative appeal was denied on November 19, 2007. This lawsuit followed. IV. Analysis FOIA provides for public access to government agency records. See 5 U.S.C. § 552. Access, however, is permitted only with respect to information that sheds light on the government’s performance of its duties. Forest Guardians v. U.S. Fed. Emergency Mgmt. Agency, 410 F.3d 1214, 1217 (10th Cir. 2005). There is a strong presumption for disclosure under FOIA and the statute’s provisions are broadly construed to effectuate this goal. Trentadue v. Integrity Comm., 501 F.3d 1215, 1226 (10th Cir. 2007). Nevertheless, FOIA includes nine exemptions which permit government agencies to withhold requested records. See 5 U.S.C. § 552(b). These exemptions are construed narrowly; the federal agency resisting disclosure bears the burden of justifying the application of an exemption. See Trentadue, 501 F.3d at 1226. In addition, to keep with the purpose of facilitating disclosure, FOIA requires governmental agencies to delete or redact any “reasonably segregable portion” that falls within an exemption 3 The parties appear to be in agreement that this request was in reference to the autopsy photographs. 3 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 4 of 16 and disclose the remainder of the record. See 5 U.S.C. § 552(b). Whether, and to what degree, a particular record is covered by an exemption is a question of law. See Trentadue, 501 F.3d at 1226. When an agency withholds documents under an exemption, the district courts have jurisdiction to review the application of the exemption de novo. See 5 U.S.C. § 552(a)(4)(B). The exemptions asserted by the Executive Office in this case are Exemption 6 and Exemption 7(C), which excuse disclosure of: (6) personnel and medical files and similar files the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy [(“Exemption 6")]; (7) records or information complied for law enforcement purposes, but only to the extent that the production of such law enforcement records or information . . . (C) could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy [(“Exemption 7(C”)]. Under Exemption 6, the term “similar files” is construed broadly and generally incorporates all information that applies to a particular individual. Trentadue, 501 F.3d at 1232 (citing U.S. Dep’t of State v. Wash. Post Co., 456 U.S. 595, 602 (1982)). The privacy interest protected by Exemption 6 is an “individual’s control of information concerning his or her person.” U.S. Dep’t of Defense v. Fed. Labor Relations Auth., 510 U.S. 487, 500 (1994) (hereinafter “FLRA”). Although similar to Exemption 6, Exemption 7(C) provides greater protection for privacy interests. U.S. Dep’t of Justice v. Reporters Comm. for Freedom of the Press, 489 U.S. 749, 756 (1989). The statutory language demonstrates this disparity in breadth. Exemption 6 covers disclosures that “would constitute” a “clearly unwarranted” invasion of privacy, whereas Exemption 7(C) extends to disclosures that “could reasonably be expected” to constitute an 4 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 5 of 16 “unwarranted” invasion of privacy.4 To determine whether and to what degree either exemption authorizes the government to withhold disclosure, a court must balance the public interest in disclosure with the private interest at stake. See id. at 776. The public interest in disclosure is that which contributes to the public’s understanding of government actions or operations. See FLRA, 510 U.S. at 495 (quoting id. at 775). When privacy interests are at stake, the requesting party must demonstrate a sufficient reason for disclosure by showing that (i) the public interest sought to be advanced is a significant interest and (ii) disclosure would likely advance the articulated public interest. See Nat’l Archives & Records Admin. v. Favish, 541 U.S. 157, 172 (2003). If the public interest asserted is to show negligence or improper action by government officials, more than conclusory allegations of government misconduct is required. See id. at 174. The requesting party is required to make a meaningful evidentiary showing of the misconduct such that a reasonable person would believe that the alleged misconduct occurred. The Supreme Court has recognized that with regard to “death scene images” the personal privacy rights under FOIA include those of the family of the deceased. Id. at 170. Death scene images include those records that reflect a death, the scene of a death, or pertain to graphic details surrounding a death. For example, death scene images in which families of the deceased have a privacy interest have included suicide scenes, the deceased’s last words (Challenger explosion), JFK’s autopsy photographs, and MLK’s assassination. In recognizing the privacy interest of family members in such records, the Supreme Court examined cultural traditions and 4 These two differences in the statutory language were the products of specific amendments to the statute. Reporters Comm., 489 U.S. at 756. 5 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 6 of 16 common law which respect a family’s right to control the disposition of the body of a loved one as well as posthumous photographs of the deceased. Cultural norms and common law traditions recognize a family’s need to honor and mourn their loved one without interference from the public. Indeed, the Supreme Court reasoned that “personal privacy” must include a family’s privacy rights, otherwise perpetrators of crimes could use FOIA to obtain and publish the death scene images of their victims, an untenable result. However, one circuit has held that the government’s reliance on an otherwise applicable exemption may be precluded if the information sought was admitted as evidence in a criminal trial. See Cottone v. Reno, 193 F.3d 550, 554 (D.C. Cir. 1999). A. Autopsy Photographs Prison Legal News seeks disclosure of the autopsy photographs of Mr. Estrella’s body. The Executive Office claims that the photographs have been properly withheld under either Exemption 6 or Exemption 7(C). As Exemption 7(C) is broader than Exemption 6, the Court will begin its analysis with Exemption 7(C). As a threshold matter, there is no disagreement between the parties that the autopsy photographs were compiled for law enforcement purposes as required by Exemption 7(C). On one side of the balancing test, the public interest in disclosure of the autopsy photographs is limited. Prison Legal News articulates the public interests as: (i) allowing the public to be fully informed about the circumstances of Mr. Estrella’s murder; and (ii) allowing the public to scrutinize the circumstances under which the government pursued the death penalty. With respect to the first articulated interest, the Court observes that the espoused public interest does not necessarily concern a governmental activity. The circumstances of a murder, 6 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 7 of 16 even one that occurs in a federal penitentiary, do not alone infer a governmental activity. In this case, there is nothing that directly links the circumstances of Mr. Estrella’s murder to a governmental activity. Prison Legal News offers nothing more than vague suggestions that perhaps a governmental employee, practice, or policy had something to do with the murder. It suggests that the BOP did not provide suitable living quarters for the three inmates or was negligent in protecting Mr. Estrella from his cellmates. Such suggestions are insufficient to demonstrate a governmental activity that warrants disclosure of government information. How the BOP responded to Mr. Estrella’s murder is arguably a governmental activity, but that takes the Court to the second justification. The government’s request for imposition of the death penalty is clearly a governmental activity. However, Prison Legal News does not tie the autopsy photographs to this decision. There is no showing that some aspect of the photographs caused, influenced, or particularly impacted the government’s decision to seek the death penalty. The photographs depict the nature of Mr. Estrella’s injuries, but they do not reveal the factors that the government considered in determining that the death penalty was a proper punishment. Therefore, disclosure would at most provide a glimpse into the government’s decision to seek the death penalty. Assuming, without determining, that the autopsy photographs did have some relationship to the government’s decision to seek the death penalty, it is also important to note that the jury in each criminal case rejected the government’s request. Had the death penalty been imposed against either William or Rudy Sablan, the public’s interest in understanding why it was requested and upon what evidence the jury based its determination could be quite significant. 7 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 8 of 16 Here, however, the public’s interest is diminished because the death penalty was not imposed. Under these circumstances a showing of the importance of the public interest and how it ties to the autopsy photographs must be more nuanced and specific. In the absence of such a showing, the Court finds that the public interest in the autopsy photographs to be small. On the other side of the balancing analysis is the family’s privacy interest. In this case, it is significant.5 Mr. Estrella’s sister and aunt are close relatives that hold a privacy right in the photographs of his autopsy. The autopsy photographs show, in detail, the exceptionally heinous nature of Mr. Estrella’s injuries. Given the graphic nature of the photographs, public dissemination of these images could impede the family’s ability to mourn Mr. Estrella’s death in private and achieve emotional closure. Balancing the family’s strong privacy interest against the public’s interest in disclosure to evaluate the government’s choice to pursue the death penalty, the Court concludes that the disclosure could reasonably result in an unwarranted invasion of privacy. Therefore, the Court finds that Exemption 7(C) applies to the autopsy photographs.6 B. Video Prison Legal News also seeks disclosure of the video depicting the treatment of Mr. 5 The Court finds Prison Legal News’s suggestion that Mr. Estrella’s family has no privacy interest in the autopsy photographs because they did not submit affidavits asserting this right unpersuasive. Exemption 7(C) does not require an assertion of the right to privacy, but protects against disclosure that could “reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.” The Court also concludes that Mr. Estrella’s family did not waive its privacy rights by not objecting to the government’s use of the video and autopsy photographs in the trials. It was the government’s, not the family’s, decision to use the materials at trial and, therefore, such use did not waive the family’s privacy interests. See Sherman v. U.S. Dep’t of the Army, 244 F.3d 357, 364 (5th Cir. 2001). 6 Because Exemption 7(C) applies, analysis of Exemption 6 is not necessary. 8 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 9 of 16 Estrella’s body following his murder. The Executive Office again asserts that both Exemption 6 and Exemption 7(C) justify its withholding of the video. The Court begins with an analysis of Exemption 7(C). Again, there is no disagreement between the parties that the video was created for law enforcement purposes as required by Exemption 7(C). After in camera review of the video, the Court finds that the video can be divided into two distinct, segregable portions: (i) William and Rudy Sablan’s actions within the prison cell (“Section One”) and (ii) the BOP’s treatment of William and Rudy Sablan during and after their removal from the cell (“Section Two”).7 Mr. Estrella’s body and injuries are clearly visible in Section One; they are completely omitted in Section Two. As to Section Two, the analysis is straightforward. Section Two falls within the scope of FOIA because it depicts the government’s operations with respect to dealing with William and Rudy Sablan following the murder. In addition, there is no family privacy interest at issue because these are not death scene images. There are, however, portions in Section Two that depict William or Rudy Sablan’s genitalia. As to these portions, the Sablans have a privacy interest. See Poe v. Leonard, 282 F.3d 123, 138–39 (2d Cir. 2001). In the absence of any apparent public interest relative to views of the Sablans’ genitalia, the Court concludes that disclosure of the video without obscuring their genitalia could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of their personal privacy. Therefore, with the exception of 7 Section One runs from the beginning of the video up through time-code 15:52 of the entire video. Section Two runs from time-code 15:52 through the end of the video. Time-code 15:52 occurs at approximately 3:52:07 a.m. as identified in the video. 9 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 10 of 16 the portions of Section Two depicting the genitalia of William and Rudy Sablan,8 the Court concludes that no exemption excuses the release of Section Two. With respect to Section One, the Court’s analysis is similar to that applied with regard to the autopsy photographs. Prison Legal News argues that disclosure would allow the public to scrutinize the BOP’s operations at USP-Florence, the size of the prison cell, the alleged intoxication of William and Rudy Sablan, the lack of a timely response by the BOP, the sharp weapon used in mutilating Mr. Estrella’s body, and the government’s decision to pursue the death penalty. Of these articulated public interests, only the size of the cell, the timeliness of the response of BOP officials, and the government’s decision to seek the death penalty relate to governmental activity. Although at least some of these are arguably significant interests that would be advanced by release of the video, others are not so clear. For example, the size of the cell is not unique to the video, and the response time is not apparent from the video, alone, because it does not reveal when BOP authorities became aware of the activities in the cell. As to these aspects, Prison Legal News offers little justification for disclosure—merely an insinuation of governmental action/inaction. As to the treatment of Mr. Estrella’s body, as noted earlier, the jury’s rejection of the government’s request for imposition of the death penalty reduces public interest in the decision. In addition, the horrendous manner in which the murder occurred which creates a public interest also is the characteristic that most greatly impacts the privacy interest of Mr. Estrella’s family. Mr. Estrella’s family has a strong privacy interest similar to that which they have in the 8 The portions of Section Two that depict William or Rudy Sablan’s genitalia should be electronically or otherwise obscured to preserve their privacy interests. 10 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 11 of 16 autopsy photographs. The video includes graphic images of Mr. Estrella’s body and injuries, which, in many ways, are more graphic than the autopsy photographs because the video was taken at the scene with the perpetrators present and continuing to act and comment. Indeed, the video depicts William Sablan’s brutal treatment of Mr. Estrella’s body following the murder. As noted earlier, public display or dissemination of these images would likely interfere with the family’s ability to mourn Mr. Estrella’s death and achieve emotional closure. The Court concludes that upon balancing the factors, the asserted public interests do not outweigh the family’s privacy interest. Therefore, with respect to Section One, the Court concludes that Exemption 7(C) is applicable.9 Although neither party has addressed segregation of the audio track from the video track, the Court addresses this issue as part of its de novo review. After close in camera review, the Court finds that the only audio portion evidencing governmental activity is that accompanying Section One. As to this section, it is the statements of BOP officials that reflect governmental action; the statements by William and Rudy Sablan fail to shed light on the government’s activities. Because Mr. Estrella’s family has no privacy interest in statements by BOP officials, the statements are not subject to either Exemption 6 or 7(C). Accordingly, the statements of BOP officials in Section One are subject to disclosure under FOIA. C. Public Domain Notwithstanding any exemption, Prison Legal News argues that the video and autopsy photographs entered the public domain when they were admitted as evidence at the Sablan trials. Because they entered the “public domain”, Prison Legal News contends that no exemption 9 Therefore, analysis of Exemption 6 is not necessary. 11 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 12 of 16 applies. Prison Legal News bases this argument upon the opinion of the D.C. Circuit in Cottone v. Reno, 193 F.3d 550, 554 (D.C. Cir. 1999). Due to distinguishable facts, the Court finds the reasoning in Cottone unpersuasive. As in this case, in Cottone, evidence presented in a criminal trial was later sought through a FOIA request. Mr. Cottone was convicted, then requested copies of documents and tape recordings that mentioned his name, including wiretap tapes used at his trial. The government disclosed many documents and two tape recordings, which it heavily redacted. The government claimed Exemption 310 excused disclosure of certain wiretap tape recordings because Title III of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (“Title III”) required secrecy of intercepted material. Mr. Cottone argued that the government had waived Exemption 3 by playing the tape recordings at his trial. He characterized the presentation of the evidence at trial as it having been placed in the “public domain”. The D.C. Circuit observed that Exemption 3 and Title III would ordinarily excuse the disclosure of the wiretapped recordings under FOIA. The D.C. Circuit referred to the wiretap evidence as having entered the “public domain”, but it essentially reasoned that when the government made the information public by presenting it at trial, there was no purpose for maintaining its secrecy. Essentially, the government had waived its right to assert a secrecy interest or obligation under Exemption 3. 10 Exemption 3 excuses disclosure for matters that are: specifically exempted from disclosure by statute (other than section 552b of this title), provided that such statute (A) requires that the matters be withheld from the public in such a manner as to leave no discretion on the issue, or (B) establishes particular criteria for withholding or refers to particular types of matters to be withheld[.] 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(3). 12 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 13 of 16 Cottone is limited by its facts and its reasoning. First, and most importantly, Cottone concerns only Exemption 3, which addresses governmental obligations to maintain confidentiality of certain information. Exemption 3 does not address individual privacy rights. The court in Cottone dealt with two competing public interests—the public interest in disclosure and the public interest in maintaining the secrecy of certain governmental information. It did not address a balancing between a public interest in disclosure and individual privacy rights such as those of family members in materials that reflect the death of their beloved. Second, implicit in Cottone is an underlying notion that the government could waive its right or extinguish its obligation to keep information secret through its prosecutorial actions. The court did not address, nor did it need to address, whether the government in its prosecutorial capacity can waive or extinguish privacy rights of individuals. As to this issue, Prison Legal News has not cited and the Court is not aware of any court that has determined that the public domain doctrine as applied in Cottone trumps personal privacy interests under FOIA. Indeed, the Fifth Circuit has declined to extend the Cottone reasoning in this way. See Sherman v. U.S. Dep’t of the Army, 244 F.3d 357, 364 n.13 (5th Cir. 2001). With these limitations, Cottone offers little guidance to this Court. It simply does not stand for the proposition asserted by Prison Legal News that once evidence is presented at trial, that it has entered the public domain and therefore all privacy interests under FOIA are extinguished. Undoubtedly, there could be circumstances where information is so public that it might negate a personal privacy exemption under FOIA.11 One could imagine, for example, death scene material that has become so widespread in the media or on the internet that 11 Or it could eliminate the need for a FOIA request. 13 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 14 of 16 maintaining the privacy interest of a deceased’s family is impractical. One could also imagine that a person with a privacy interest could waive such interest by voluntarily disclosing death scene material to the media or voluntarily testifying with regard to it during a trial or another legal proceeding. There has been no showing in this case, however, of such circumstances. It does not appear that the autopsy photographs or the video entered the public domain except as part of the Sablan trials and trial record. With regard to that record, the government may have waived it’s right to assert an interest in confidentiality of the information, but one cannot assume that it waived the individual privacy rights of Mr. Estrella’s family. Ordinarily, family members of a murder victim do not decide whether a trial occurs nor control the selection of the evidence to be admitted. Therefore, the presentation of evidence in which they have a privacy right at a criminal trial would not automatically constitute a waiver of their rights. Indeed, no showing of any waiver by Mr. Estrella’s family has been made. Even assuming that some waiver had been shown, this Court would nevertheless be cautious in concluding that presentation of evidence in a criminal trial would automatically vitiate individual privacy rights under a FOIA exemption. In Reporters Comm., 489 U.S. at 763–70, the Supreme Court recognized that privacy interests are not necessarily extinguished by previous limited public disclosure. Reporters Comm. addressed disclosure of an individual’s “rap sheet”—the government’s comprehensive compilation of public criminal records on a particular individual. The Supreme Court reasoned that because the passage of time and/or the limited circumstances of the earlier disclosure could result in the information being forgotten, it was possible for an individual to maintain a privacy interest in the information regardless of the 14 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 15 of 16 previous disclosure. Therefore, the Supreme Court categorically concluded that further disclosure of the rap sheets could reasonably be expected to invade the individual’s privacy, notwithstanding that the information was otherwise publicly available. Here, the scope of the public exposure associated with a criminal trial is vastly different from the public exposure that can result from the release of the same information pursuant to FOIA. A trial is of limited duration, and once completed, the evidence presented becomes part of the trial record. This record may never have public exposure, and even under the worst of circumstances - a reversal of a conviction and subsequent retrial - the death scene evidence would have public exposure only for a limited time and a limited purpose. In contrast, the release of death scene material through FOIA is absolute, unrestrained, and perpetual. Once released, the information can be publically displayed, by multiple persons, in multiple venues, and on multiple occasions. A decedent’s family would have no expectation that the exposure would necessarily end. For these reasons, the Court concludes that use of the autopsy records and video at the Sablan trials does not negate the application of Exemption 7(C). IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED that: (1) Defendant Executive Office for United States Attorneys’ Motion for Summary Judgment (#18) is GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED IN PART. (2) Prison Legal News’s Motion for Summary Judgment (#20) IS GRANTED IN PART AND DENIED IN PART. (3) Defendant Executive Office shall disclose to Plaintiff Prison Legal News only (i) the portion of the video that does not depict Mr. Estrella’s body (Section Two - all 15 Case 1:08-cv-01055-MSK-KLM Document 26 Filed 09/16/2009 USDC Colorado Page 16 of 16 portions after time-code 15:52) except it shall electronically or otherwise obscure the video portion showing William Sablan or Rudy Sablan’s genitalia and (ii) the audio of BOP officials in the remaining portion of the video (Section One - all portions prior to time-code 15:52). (4) This Order having resolved all issues in this case, the Clerk of the Court is directed to close the case. Dated this 16th day of September, 2009 BY THE COURT: Marcia S. Krieger United States District Judge 16