Prison Legal News v. Livingston et al., TX, Order, TDCJ censorship, 2011

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

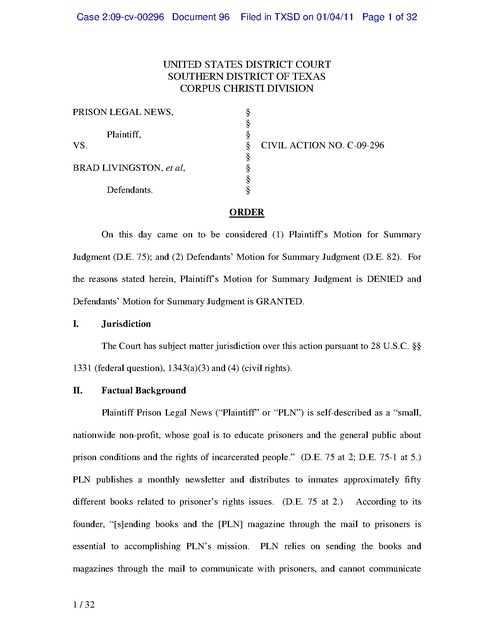

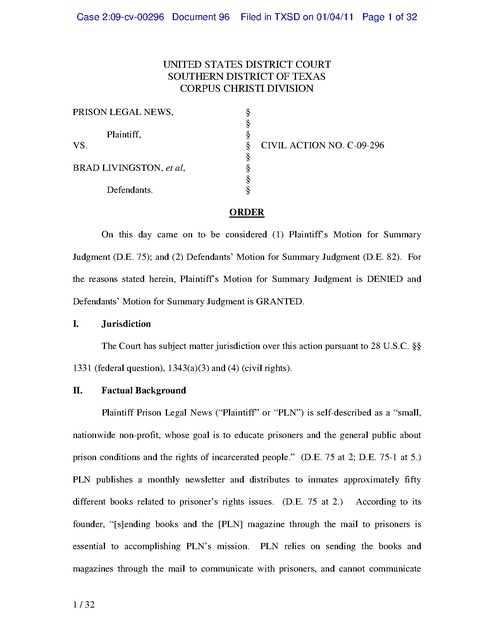

Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 1 of 32 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS CORPUS CHRISTI DIVISION PRISON LEGAL NEWS, Plaintiff, VS. BRAD LIVINGSTON, et al, Defendants. § § § § § § § § CIVIL ACTION NO. C-09-296 ORDER On this day came on to be considered (1) Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 75); and (2) Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 82). For the reasons stated herein, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED and Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment is GRANTED. I. Jurisdiction The Court has subject matter jurisdiction over this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 (federal question), 1343(a)(3) and (4) (civil rights). II. Factual Background Plaintiff Prison Legal News (“Plaintiff” or “PLN”) is self-described as a “small, nationwide non-profit, whose goal is to educate prisoners and the general public about prison conditions and the rights of incarcerated people.” (D.E. 75 at 2; D.E. 75-1 at 5.) PLN publishes a monthly newsletter and distributes to inmates approximately fifty different books related to prisoner’s rights issues. (D.E. 75 at 2.) According to its founder, “[s]ending books and the [PLN] magazine through the mail to prisoners is essential to accomplishing PLN’s mission. PLN relies on sending the books and magazines through the mail to communicate with prisoners, and cannot communicate 1 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 2 of 32 with prisoners without being able to use the mail.” (D.E. 75-1 at 5.) Among those prisoners with whom PLN communicates are those within facilities run by the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (“TDCJ”), a 96 unit system that incarcerates approximately 139,000 offenders. (D.E. 82-2 at 4.) On November 4, 2009, PLN filed this lawsuit against Defendant Brad Livingston, director of the TDCJ, and several other TDCJ officials, claiming that Defendants violated PLN’s First Amendment and due process rights when it censored1 two books, Women Behind Bars and Perpetual Prisoner Machine, which PLN sought to send to prisoners at TDCJ facilities. (D.E. 1.) Since filing suit, PLN has twice amended its complaint, most recently on July 30, 2010. (D.E. 67.) Named as defendants in PLN’s Second Amended Complaint are Brad Livingston, Jennifer Smith (program specialist for TDCJ’s Mail System Coordinators Panel), Ramona Creek (mailroom clerk at the TDCJ Garza East Unit), and Sue Weeks (mailroom representative at the TDCJ Hilltop Unit). Livingston is sued solely in his official capacity, whereas Smith, Creek, and Weeks are sued solely in their individual capacities. (D.E. 67 at 1-3.) In its Second Amended Complaint, PLN alleged that Defendants censored the following five books that it attempted to distribute to prisoners at TDCJ facilities: Women Behind Bars: The Crisis of Women in the U.S. Prison System, by Silja J.A. Talvi; Perpetual Prisoner Machine: How America Profits from Crime by Joel Dyer; Soledad Brother: The Prisoner Letters of George Jackson, by George Jackson; Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis, by Christian Parenti; and Prison Masculinities, by Don Sabo, Dr. Terry Kupers, and Willie London. 1 The Court understands that Defendants object to use of the word “censor” in this context, as “misleading, incomplete, vague, overbroad, and confusing.” (See D.E. 75-1 at 18.) The Court uses this term simply as an alternative to “disapprove” or “deny,” without any negative connotation. 2 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 3 of 32 (D.E. 67 at 3-9.) PLN states that it was never notified that the books at issue were disapproved by the TDCJ. (D.E. 67.) Rather, PLN found out that its books were disapproved when the books were returned in the mail, during the discovery process, or upon receipt of an e-mail from the author. (D.E. 75-1 at 7-8.) The reasons for disapproving these books vary, and may be briefly summarized as follows: (1) Women Behind Bars: This book is described as a “comprehensive and passionately argued indictment of the inhuman treatment of female prisoners.” (D.E. 67 at 4.) PLN states that TDCJ disapproved the publication because page 38 depicted “sex with a minor.”2 It was originally denied in April 2008, and subsequently denied in November 2008, when it was sent to inmate Lou Johnson at the TDCJ Hilltop Unit. (D.E. 67 at 4-5; see also D.E. 75 at 6-10; D.E. 75-1 at 20-21, 41; D.E. 82-12.) Lou Johnson appealed the denial, but the decision was upheld on December 3, 2008. (D.E. 82-2 at 13.) Women Behind Bars was denied to other inmates on other occasions as well. (D.E. 82-2 at 15.) On July 30, 2010, Defendant Smith re-reviewed Women Behind Bars and determined that it should be approved. (D.E. 82-2 at 11.) (2) Perpetual Prisoner Machine: This publication is described as “a critique of the for-profit prison industry.” (D.E. 67 at 6.) PLN states that this publication was ordered 2 The relevant passage read as follows: What is even more remarkable about [Tina] Thomas [a medical doctor incarcerated in Oklahoma] is that she had overcome the kind of childhood trauma that might have completely derailed her adult life. It might have been precisely that background that first propelled her to become an overachiever and attain a high level of professional success, but then came back to haunt her just as she had gotten to where she wanted to go. The dark secret of her life was that she had been forced to perform fellatio on her uncle when she was just four years old. Thomas explains that this unresolved trauma became “the template for a lifetime of distrust, fear, uncertainty, and a spirit of self-negation.” (D.E. 75-3 at 21.) 3 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 4 of 32 by a prisoner at TDCJ’s Allred Unit, and was denied because “page 45 discusses ‘rape.’” (D.E. 75-3 at 77.) This book was originally denied on February 15, 2000, and subsequently denied on February 25, 2009 at the Allred Unit. (D.E. 67 at 6; see also D.E. 75 at 10-13; D.E. 75-1 at 22; D.E. 82-2 at 15, 16 D.E. 82-16.)3 (3) Soledad Brother: This book is “a collection of letters by George Jackson, a member of the Black Panthers, who was imprisoned in California’s Soledad prison in the 1960s.” (D.E. 67 at 6.) TDCJ disapproved this book because “page xxiii is ‘racial.’” (D.E. 75-4 at 9.) Other denials note that the “entire publication advocates overthrow of prisons by riots and revolt.” (D.E. 82-26 at 2, 4, 7.) The book was initially denied at the Connally Unit on August 10, 2005. (D.E. 67 at 7; see also D.E. 75 at 13-14; D.E. 75-1 at 3 The relevant passages read as follows: I was laying in my bed when seven or eight inmates came to my bed, pulled the blankets off me, put it on the floor and told me to pull my pants down and lay face down on the blanked. I said, “No,” and was punched in the face by one of the inmates. The inmate that punched me stated if I did not get on the floor the other inmates would gang up on me. I got on the floor and my pants and shorts were pulled off. Two inmates spread and held my legs apart while two more inmates held my hands in front of me. While I was being buggered from behind another inmate would make me suck his penis. This continued until all the inmates had attacked me and I heard one of them say it was 1:30 AM, so let’s go to bed. They put me on the bed, covered me with the blanket and one of them patted me on the behind saying, “Good boy, we will see you again tomorrow night.” A second passage reads: I was in the cell at 1801 Vine when four Negro boys started bothering me for not having underwear on. Then when we got on the Sheriff’s van and started moving they told everyone that I didn’t have on underwear . . . they started moving close to me. One of them touched me and I told them to please stop. All of a sudden a coat was thrown over my face and when I tried to pull it off I was viciously punched in the face for around ten minutes. . . . They ripped my pants from me while five or six of them held me down and took turns fucking me. . . . My insides feel sore and my body hurts, my head hurts, and I feel sick in the stomach. Each time they stopped I tried to call for help but they put their hands over my mouth . . . (D.E. 75-3 at 100.) 4 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 5 of 32 23.)4 Defendant Smith subsequently decided to remove Soledad Brother from the denied book list in July 2010. (D.E. 82-2 at 17.) (4) Lockdown America: This book is described as “a history of the prison expansion that began in America in the 1970s.” (D.E. 67 at 7.) TDCJ disapproved this book because “page 206 is ‘racial.’” (D.E. 75-4 at 50.) This title was originally denied on June 5, 2000. (D.E. 67 at 7-8; see also D.E. 75 at 15-16; D.E. 75-1 at 23; D.E. 82-2 at 17.)5 (5) Prison Masculinities: This publication is a “collection of essays about prison conditions by distinguished authors.” (D.E. 67 at 8.) It was disapproved because “pages 128-131 contain rape” and “pages 194 + 222 – contain racial material.” (D.E. 75-4 at 91.) Prison Masculinities was originally denied on May 24, 2001, and subsequently denied on December 12, 2009 at the Powledge Unit. (D.E. 67 at 8; see also D.E. 75 at 16-18; D.E. 75-1 at 22; D.E. 82-2 at 17; D.E. 82-23 at 2.)6 4 The relevant passage provides: Race is more times than not the easy answer to a problem. Among people of color in the United States, the quick fix, “blame it on whitey” mentality has become so prevalent that it shortcuts thinking. Conversely, stereotypes of minorities act as simple-minded tools of divisiveness and oppression. George addressed these issues in prison, setting a model for the outside as well: “I’m always telling the brothers some of those whites are willing to work with us against the pigs. All they got to do is stop talking honky. When the races start fighting, all you have is one maniac group against another. (D.E. 75-4 at 24.) 5 The relevant passage provides: “Another group of screws at the California Institution for Men at Chino called itself SPONGE, a disgusting acronym for the equally disgusting name, ‘Society for the Prevention of Niggers Getting Everything.’” (D.E. 75-4 at 79.) 6 The relevant passages in this book discuss an inmate being “raped and beaten by Blacks as a punishment for permitting [himself] to be raped by Whites,” and that “getting fucked by a tender, gentle jock was better than the vicious gang-bangs and there was pride in making my man happy in bed . . . The s & m freaks . . . always scared the hell out of me and were the worse [sic] of all the jocks in any joint I was in.” The passages discuss repeated sexual assaults and rapes of an inmate who was a teenager at the time, some of which are quite graphic. (D.E. 75-5 at 5-9.) The “racial” material on pages 194 discusses officers “calling [an inmate] a ‘nigger’ as the other guards laugh . . . .,” and page 222 contains the following passage: “Black people can get on the radio and use the words ‘nigger’ and ‘bitch.’ To me, that’s serious. If you think 5 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 6 of 32 PLN claims that, for all publications at issue except Soledad Brother, it has encountered no instances of censorship with respect to those titles at any other correctional facility in the United States. (D.E. 75-1 at 6-7.) The TDCJ book review process begins when a book arrives at a TDCJ mailroom. There, a mailroom employee first checks the TDCJ database to determine whether the book has previously been approved or rejected. If the book has been previously rejected, as stated in the database, mailroom staff will not re-review the book; rather, they will simply notify the offender that the book is not allowed. (D.E. 82-2 at 8-9.) If the book has not been previously considered, the employee begins to review the book. (D.E. 75-1 at 39; see also D.E. 75-1 at 50; D.E. 82-2 at 7; D.E. 82-4.) TDCJ policy permits disapproval of a book when: (1) it contains contraband that cannot be removed; (2) it contains information regarding the manufacture of explosives, weapons, or drugs; (3) it contains material that a reasonable person would construe as written solely for the purpose of communicating information designed to achieve the breakdown of prisons through offender disruption such as strikes, riots, or security threat group activity; (4) a specific determination has been made that the publication is detrimental to offenders’ rehabilitation because it would encourage deviant criminal sexual behavior; (5) it contains material on the setting up and operation of criminal schemes; or (6) it contains sexually explicit images.7 white people are going to stop us from calling us niggers and bitches, you’re crazy. We’ve got to stop degrading ourselves.” (D.E. 75-5 at 21.) 7 This last section also provides: “Publications shall not be prohibited solely because the publication displays naked or partially covered buttocks. Subject to review by the MSCP and on a case-by-case basis, publications constituting educational, medical/scientific or artistic materials, including but not limited to, anatomy medical reference books, general practitioner reference books and/or guides, National Geographic or artistic reference material depicting historical, modern and/or post modern era art, may be permitted.” (D.E. 75-1 at 106.) 6 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 7 of 32 (D.E. 75-1 at 105-106 (TDCJ Board Policy BP-03.91)). With respect to the fourth category, “deviant criminal sexual behavior,” Defendant Smith testified that there is no precise definition of which she was aware to apply in this category, and that there are various “rules of thumb” for denying certain nude artwork. (D.E. 75-1 at 75, 78.) For example, art “that has got more of a pornographic edge to it,” as opposed to “historical art that’s everywhere in museums,” may be denied, as would certain naked pictures of children in, for example, National Geographic. (D.E. 75-1 at 79.) Defendant Smith testified during her deposition that “if a mailroom clerk or mailroom supervisor feels that something needs to be denied, [she] always tell[s] them to err on the side of caution. Go ahead and deny it and give that offender the right to appeal . . . and let someone else take a look at it instead of putting the burden on them to make that sort of decision.” (D.E. 75-1 at 74.) Once a problematic passage is found, TDCJ staff does “not attempt to determine whether the remainder of the book contains other content which is not in violation of policy or which would ‘outweigh’ this reference.” Instead, the entire publication is denied based upon the one passage at issue. (D.E. 82-2 at 13.) Once the decision is made to disapprove a book at the unit level, the employee completes a “Publication Review/Denial” form and sends the form to the prisoner who had ordered the book. (D.E. 75-1 at 40; D.E. 75-1 at 106 (BP-03.91, describing notice procedures).) The prisoner may then appeal the decision to the Director’s Review Committee (“DRC”) if the decision as to that particular book has not been previously appealed. The DRC delegates its review authority to the Mail Systems Coordinators Panel (“MSCP”), which is composed of two TDCJ employees, including Defendant 7 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 8 of 32 Smith, the MSCP chair. Smith states that she reviewed “8-9 books per day that come to [her] office on appeal, in addition to [her] other duties.” (D.E. 82-2 at 19.) If the MSCP members cannot reach a unanimous decision as to a particular book, the book is forwarded to the DRC as a whole for further review. None of the books at issue in this litigation reached the full DRC. Once the DRC/MSCP makes a decision, there is no further appeal, at least absent republication of the book without the material that led to the initial disapproval. (D.E. 75 at 4-5; D.E. 75-1 at 21, 40; D.E. 75-1 at 67; D.E. 75-1 at 108-109 (BP-03.91, describing appeal procedures); D.E. 82-2 at 8, 11; D.E. 90-1 at 34; see generally D.E. 82-3.) The prior TDCJ policy required only that notice be sent to the prisoner, not the sender of the book, unless the sender was also the editor and/or publisher. This policy was changed in February 2010, to include notice to the sender. (D.E. 75 at 5 n. 33; D.E. 75-1 at 70; D.E. 75-1 at 120 (B.P 03.91, Feb. 2010 revision); D.E. 82-11.) PLN contends that, in practice, the TDCJ sends a rejection form to the sender only when the DRC/MSCP has not already censored a book after an appeal. If the book has already been disapproved by DRC/MSCP, there is no notice and no appeal. (D.E. 75 at 6.) PLN states that DRC/MSCP receives fewer than ten appeals from senders each year; the vast majority of appeals originate from prisoners. (D.E. 75 at 6.) III. Procedural Background In its Second Amended Complaint, filed on July 30, 2010, PLN brought claims for violation of its First Amendment and due process rights, and sought declaratory relief, injunctive relief, damages, and attorney’s fees. (D.E. 67 at 10-11.) The Court has since 8 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 9 of 32 dismissed Plaintiff’s due process claims against Defendants in their individual capacities on qualified immunity grounds. (D.E. 53 at 14; D.E. 66.) Plaintiff and Defendants filed cross-motions for summary judgment on October 15, 2010. (D.E. 75; 82.)8 The parties filed their respective responses on November 8, 2010. (D.E. 89; 90.)9 Defendants argue various bases for dismissal of this action. Defendants contend that Plaintiff’s claims must fail because (1) PLN is not the publisher of any of the books at issue (and thus lacks First Amendment rights), (2) even if PLN has First Amendment rights, it cannot demonstrate that any inmate requested certain books that PLN sent (and lacks a First Amendment right to send unsolicited books to inmates), and (3) even if PLN can demonstrate that inmates requested the books at issue, PLN cannot overcome the considerable deference to which prison administrators’ disapproval decisions are entitled. (D.E. 82.) Defendants also argue that Smith, Weeks, and Creek are entitled to qualified immunity, that Creek is entitled to dismissal for lack of personal involvement, and that punitive damages are unwarranted. (D.E. 20-24.) 8 Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment was initially filed on October 15, 2010, but struck for procedural reasons. (D.E. 77.) It was properly refiled on October 18, 2010. (D.E. 82.) 9 Defendants have also filed, inter alia, a Motion to Strike (D.E. 87). Defendants seek to strike (1) Exhibits 8(a)-(c) (a purported TDCJ approved/denied book list), (2) Exhibits 12 and 32 (related to Women Behind Bars), (3) Exhibit 18 (a second purported TDCJ approved book list), (4) Exhibit 21 (preface to Blood in my Eye), (5) Exhibits 24 and 27 (declarations by Christian Parenti and Terry Kupers), (6) Exhibit 30 (declaration of Ron McAndrew), and (7) Exhibit 31 (BOP policies). The Court DENIES AS MOOT the Motion to Strike with respect to Exhibits 21 and 24, since this Court dismisses, infra, Plaintiff’s claims with respect to Soledad Brother and Lockdown America. As to Defendants’ other objections on relevancy grounds, the Court finds that the evidence is sufficiently relevant under Federal Rule of Evidence 401 to avoid being struck, even though it is not controlling on the issues presented to the Court, as discussed further herein. Fed. R. Evid. 401. The Court therefore DENIES the Motion to Strike with respect to Exhibits 12, 32, 27, and 31. With respect to Exhibits 8(a)-(c) and 18, the Court does not share Defendants’ concerns as to authentication or admissibility. Indeed, Defendants do not specifically allege that anything in those large exhibits is inaccurate. Plaintiff’s summary is admissible under Fed. R. Evid. 1006. The Court therefore DENIES the Motion to Strike with respect to Exhibits 8(a)-(c) and 18. Finally the Court does not reach the question of the admissibility of the testimony of expert Ron McAndrew (Exhibit 30), as this Court’s grant of Defendant’s motion for summary judgment precludes a ruling on the Motion to Exclude. (D.E. 76.) 9 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 10 of 32 Plaintiff’s own summary judgment motion argues, inter alia, that Defendant’s disapproval decisions are arbitrary and not “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.” (D.E. 75 at 18-22.) IV. Discussion A. Summary Judgment Standard Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 56, summary judgment is appropriate if “the movant shows that there is no genuine dispute as to any material fact and the movant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(a). The substantive law identifies which facts are material. See Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986); Ellison v. Software Spectrum, Inc., 85 F.3d 187, 189 (5th Cir. 1996). A dispute about a material fact is genuine only “if the evidence is such that a reasonable jury could return a verdict for the nonmoving party.” Anderson, 477 U.S. at 248; Judwin Props., Inc., v. U.S. Fire Ins. Co., 973 F.2d 432, 435 (5th Cir. 1992). On summary judgment, “[t]he moving party has the burden of proving there is no genuine issue of material fact and that it is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.” Rivera v. Houston Indep. Sch. Dist., 349 F.3d 244, 246 (5th Cir. 2003); see also Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 323 (1986). If the moving party meets this burden, “the non-moving party must show that summary judgment is inappropriate by setting forth specific facts showing the existence of a genuine issue concerning every essential component of its case.” Rivera, 349 F.3d at 247. The nonmovant’s burden “is not satisfied with some metaphysical doubt as to the material facts, by conclusory allegations, by unsubstantiated assertions, or by only a scintilla of evidence.” Willis v. Roche Biomedical Labs., Inc., 61 F.3d 313, 315 (5th Cir. 1995); see also Brown v. Houston, 337 10 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 11 of 32 F.3d 539, 541 (5th Cir. 2003) (stating that “improbable inferences and unsupported speculation are not sufficient to [avoid] summary judgment”). Summary judgment is not appropriate unless, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the non-moving party, no reasonable jury could return a verdict for that party. Rubinstein v. Adm’rs of the Tulane Educ. Fund, 218 F.3d 392, 399 (5th Cir. 2000). B. First Amendment Rights of Book Distributors 1. First Amendment Rights are Clearly Established Defendants first contend that book distributors, such as PLN, do not have clearly established First Amendment rights. As such, Defendants argue, PLN must establish that it is a publisher of the materials at issue, and that those materials were in fact requested by inmates, to obtain First Amendment protection. (D.E. 82 at 7-10.) As this Court has previously explained, “[a]lthough no case has directly addressed the First Amendment rights of distributors who seek to send books or other publications to prisoners, the cases discussed [in the Court’s December 17, 2009 Order] firmly establish that First Amendment protections apply not only to readers and publishers, but to book distributors as well, and may be invoked when a distributor seeks to challenge a governmental action that interferes with its constitutional rights.” (D.E. 32 at 15-16 (emphasis added).) These constitutional rights are clearly established, and the Court does not interpret Thornburgh v. Abbott as establishing a bright-line rule limiting First Amendment protections in the prison context to publishers alone. This is particularly so in light of earlier Supreme Court precedent acknowledging the importance of distributors in the exercise of free speech rights. See, e.g., Smith v. 11 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 12 of 32 California, 361 U.S. 147, 150 (1959) (“[I]t . . . requires no elaboration that the free publication and dissemination of books and other forms of the printed word furnish very familiar applications of these constitutionally protected freedoms [of the press and of speech]. It is of course no matter that the dissemination takes place under commercial auspices. Certainly a retail bookseller plays a most significant role in the process of the distribution of books.”); Lerman v. Flynt Distributing Co., 745 F.2d 123, 139 (2d Cir. 1984) (“First Amendment guarantees have long been recognized as protecting distributors of publications.”). Defendants’ arguments to the contrary are unavailing. Consistent with its earlier holding in this case, the Court concludes that PLN has clearly established First Amendment rights as a book distributor, akin to those of a publisher. 2. First Amendment Rights Are Contingent Upon a Willing Recipient Defendants contend that PLN’s First Amendment rights are dependent upon, or derivative of, an offender’s First Amendment rights, such that PLN only has the right to distribute publications to those offenders who order those materials. (D.E. 82 at 9, 1113.) Defendants’ basis for their argument is the Supreme Court’s decision in Thornburgh v. Abbott, wherein the Court stated that “publishers who wish to communicate with those who, through subscription, willingly seek their point of view have a legitimate First Amendment interest in access to prisoners.” 490 U.S. at 408 (emphasis added). They argue that, because no TDCJ offender ordered three of the books at issue (Women Behind Bars, Lockdown America, or Soledad Brother), PLN has no First Amendment claim with respect to these publications. (D.E. 82 at 11-13.) In response, PLN disputes Defendants’ contentions with respect to Women Behind Bars, but essentially concedes that no inmate specifically ordered Lockdown America or Soledad Brother. (D.E. 90 at 12 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 13 of 32 12 (“PLN undisputedly sent Prison Masculinities, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Women Behind Bars to prisoners who specifically sought the books or PLN’s ‘point of view.’”).) With respect to Lockdown America and Soledad Brother, PLN contends that its rights to send individually addressed books to certain inmates, even absent subscription, is protected under the First Amendment and distinguishable from prohibitions on “bulk mailings.” (D.E. 90 at 13-14.) The issue of whether a distributor such as PLN has a freestanding right to send unsolicited books to prisoners has rarely been addressed in the federal courts. The Supreme Court in Jones v. North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc., 433 U.S. 119, 131 (1977) upheld a ban on junk mail sent indiscriminately to all inmates, but the unsolicited books at issue here were addressed and sent to individual prisoners. In Prison Legal News v. Lehman, the Ninth Circuit addressed “whether a ban on non-subscription bulk mail and catalogs is . . . unconstitutional.” 397 F.3d 692, 699 (9th Cir. 2005). In that case, the court made clear that mail from PLN was “sent as a result of a request by the recipient.” Id. at 700. The court confirmed that “it is the request on the part of the receiver and compliance on the part of the sender, and not the payment of money, that is relevant to the First Amendment analysis.” Id. at 701 (emphasis added). Other courts within the Ninth Circuit have considered, but not decided, whether a publisher or distributor has a First Amendment right to send books or other materials to inmates who have not specifically subscribed or otherwise requested those materials. See Hrdlicka v. Cogbill, 2006 WL 2560790, at *8 (N.D. Cal. Sep. 1, 2006) (“in the absence of authority indicating that a publisher’s First Amendment interest in communicating with inmates is contingent on an inmate first expressing an interest in receiving such information, the 13 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 14 of 32 fact that [publication] is unsolicited does not compel the conclusion that Plaintiffs, as publishers, lack any First Amendment interest in distributing their magazine. . . . [T]he Court assumes, without deciding, that Plaintiffs have a First Amendment interest in distributing their unsolicited, non-subscription publication to Sonoma County inmates.”) (emphasis added); see also Crime, Justice & America, Inc. v. McGinness, 2009 WL 2390761, at *4 n.4 (E.D. Cal. Aug. 3, 2009) (noting, but declining to address the issue of whether plaintiffs had a First Amendment right to distribute their unsolicited publication to inmates). Nevertheless, the Court has found no relevant authority within the Fifth Circuit on this issue. In the absence of any such authority, the Court must rely upon the Supreme Court’s statement in Thornburgh that “publishers who wish to communicate with those who, through subscription, willingly seek their point of view have a legitimate First Amendment interest in access to prisoners.” 490 U.S. at 408 (emphasis added); see also id. at 411 n.9. Although the Court has found a sufficient basis to extend Thornburgh to include non-publisher distributors, it finds no such basis to extend it beyond distributions to recipients who ordered or otherwise willingly sought the books at issue. Thus, without demonstrating that at least one TDCJ inmate willingly sought PLN’s books, Plaintiff cannot state a valid First Amendment claim with respect to those books. There is no dispute that prisoners in fact ordered Prison Masculinities and Perpetual Prisoner Machine. (D.E. 82 at 11; see D.E. 75-4 at 1 (inmate Michael W. Jewell stating that his wife ordered Prison Masculinities for him from PLN in October 2005 and November 2009).) As to Women Behind Bars, PLN has presented sufficient evidence that the TDCJ recipients “willingly” sought this publication, even if PLN also 14 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 15 of 32 sent copies of the book to test for censorship, and the book was not sent in exchange for payment. (D.E. 90-1 at 40 (letter from Rudy Martinez, stating “I’m sharing the PLN with guys in here who are amazed at what they are reading in the PLN and the excellent book Women Behind Bars”); 41 (letter from Alan Wade Johnson, stating “I received [Women Behind Bars] on July 30, 200. In the future, if PLN needs to challenge such a censorship, you are welcome to forward same to me.”); 45 (letter from Michael Pitman, stating “thank you for [Women Behind Bars] and happy to have been some service to you.”); see also D.E. 75-5 at 54-55 (declaration of inmate at Segovia Unit stating that, upon receiving notice that Women Behind Bars was denied, he filed grievances to obtain the book); D.E. 82-18 at 4 (letter from Woodrow Miller at Garza East Unit requesting that another copy of Women Behind Bars be forwarded to him, “with the objectionable content redacted.”); but see D.E. 82-14 (discussing proposal to send books to TDCJ prisoners to “see what happens”); see generally D.E. 82-28 (deposition of Paul Wright); D.E. 90-1 at 2 (second declaration of Paul Wright, stating that some copies of Women Behind Bars were sent to test for censorship).) Plaintiff, however, has not submitted any evidence that any TDCJ inmate ordered or otherwise sought Lockdown America or Soledad Brother. As such, PLN does not have standing to pursue a First Amendment claim with respect to either of these books. PLN’s claims with respect to these two books (Lockdown America and Soledad Brother) must therefore be dismissed. Plaintiff’s claims with respect to Women Behind Bars, Prison Masculinities, and Perpetual Prisoner Machine, however, may proceed to the next stage of the analysis.10 10 Even if, as Defendants suggest, PLN “impermissibly sat on its rights” with respect to Women Behind Bars by “ignor[ing] TDCJ’s appeal process,” (D.E. 82 at 13-14) this would have no effect on PLN’s ability to bring this action. As PLN correctly notes, there is no “administrative exhaustion” requirement with respect to its Section 1983 claim. See Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452, 472-73 (1974) (“When federal 15 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 C. Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 16 of 32 Facial Validity vs. As-Applied Challenge 1. Facial Validity Not Disputed Defendants state that the TDCJ offender correspondence rules, as written, are constitutional as a matter of law under Guajardo v. Estelle, 580 F.2d 748 (5th Cir. 1978), which developed guidelines to be followed before TDCJ could refuse delivery of correspondence to inmates. The Fifth Circuit reaffirmed the rules’ constitutionality after Thornburgh. (D.E. 82 at 6-7 (citing Thompson v. Patteson, 985 F.2d 202, 206 (5th Cir. 1993).) Plaintiff admits that its dispute lies not with the TDCJ policies as written, but rather as they are applied. (D.E. 90 at 6 (“PLN’s complaint is not that TDCJ’s policy is unconstitutional as written, but that TDCJ fails to ensure that its employees apply it in a constitutional fashion.”).). In light of the foregoing, the Court clarifies that this case does not test the facial validity of the relevant TDCJ regulations, but rather only as they have been applied in this instance. In other words, PLN’s First Amendment claims can succeed, if at all, only as an “as applied” challenge to the TDCJ regulations. The next consideration is whether PLN is in fact able to make such an “as applied” challenge. 2. PLN May Make an “As Applied” Challenge Defendants contend that PLN’s “as applied” challenge to the TDCJ regulations fail as a matter of law. Defendants argue that, since PLN’s rights are derivative of the offender’s rights, and since an offender cannot make an “as applied” challenge, PLN cannot do so either. (D.E. 82 at 10.) Plaintiff disagrees. (D.E. 90 at 6-8.) claims are premised on 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and 28 U.S.C. § 1343(3)-as they are here-we have not required exhaustion of state judicial or administrative remedies, recognizing the paramount role Congress has assigned to the federal courts to protect constitutional rights.”). Thus, whether or not PLN pursued the TDCJ appeal process is irrelevant to its First Amendment claim. 16 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 17 of 32 Defendants’ contention with respect to as applied challenges is simply incorrect. Thornburgh v. Abbott, which was brought by a class of inmates and certain publishers, involved “a facial challenge to the [BOP] regulations as well as a challenge to the regulations as applied to 46 specific publications excluded by the Bureau.” 490 U.S. at 403 (emphasis added). In the end, the Supreme Court in Thornburgh addressed only the facial validity of the BOP regulations, but remanded to the lower court “for an examination of the validity of the regulations as applied to any of the 46 publications introduced at trial as to which there remains a live controversy.” Id. at 419 (emphasis added). The Court never suggested that the as applied challenges to the BOP regulations were per se invalid. The Fifth Circuit has similarly considered “as applied” challenges from inmates, even if ultimately rejecting such challenges on other grounds. See, e.g., Leachman v. Thomas, 229 F.3d 1148, 2000 WL 1239126, at *1 (5th Cir. 2000) (considering as applied challenge to jail’s regulations, but rejecting it in light of the jail’s “valid penological interest in preventing dissemination of literature that would have a detrimental effect upon the safety and/or rehabilitation interests of the facility.”). Defendants rely upon Moore v. Dretke, 2006 WL 1663758 (S.D. Tex. June 14, 2006) and Thompson v. Patteson, 985 F.2d 202 (5th Cir. 1993) to support their conclusion that as applied challenges to TDCJ regulations must fail as a matter of law. In Thompson, the plaintiff-inmate sought to challenge the TDCJ’s decision to withhold certain books and pornographic magazines because “they would encourage deviate, criminal sexual behavior.” The Fifth Circuit explicitly noted that the plaintiff did not “argue that the defendants withheld material not properly covered by” the relevant regulation, but rather “his First Amendment claim appear[ed] to be a facial challenge to 17 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 18 of 32 the initial rule itself: he argues that the very practice of limiting access to sexually oriented materials embodied in the rule is unconstitutional.” 985 F.2d at 206 (emphasis added). Such a claim, the court rightly concluded, was foreclosed by Guajardo. Id.; see also Id. at 207 (“Thompson’s suit was not one alleging that his publications were excluded because of an improper application of the correspondence rules . . . .”). Similarly, Moore v. Dretke, which relied upon Thompson, properly concluded that an inmate’s facial challenge to the same TDCJ regulation was unavailing, after he was denied access to pornographic magazines such as Penthouse, Gallery, and High Society. 2006 WL 1663758, at *6. Neither Thompson nor Moore stand for the proposition that “as applied” challenges to TDCJ regulations are prohibited (by publishers, distributors, or inmates) as a matter of law. Plaintiff is allowed to challenge Defendants’ application of the TDCJ regulations to the books it has distributed to willing recipients in this litigation (Prison Masculinities, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Women Behind Bars). D. Reasonable Relationship to Legitimate Penological Interests The core dispute in this litigation is whether Defendants’ decision to disapprove the books at issue violated PLN’s First Amendment rights. (D.E. 75 at 18-23; D.E. 82 at 14-19.) The court first reviews the applicable law, then considers its application with respect to Defendants’ decisions regarding Prison Masculinities, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Women Behind Bars. 1. Applicable Law A court must review prison regulations that encroach on fundamental constitutional rights under the standard set forth by the Supreme Court in Turner v. Safley, to determine whether the regulation is “reasonably related to legitimate 18 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 19 of 32 penological interests.” Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987); Mayfield v. Tex. Dep’t Crim. Just., 529 F.3d 599, 607 (5th Cir. 2008). The Turner factors are applicable to both facial and as-applied challenges to prison regulations. See, e.g., Shaw v. Murphy, 532 U.S. 223, 232 (2001) (“Under Turner, the question remains whether the prison regulations, as applied to Murphy, are ‘reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.’”); Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 414. The burden is on the party challenging the regulation at issue, not the state. Overton v. Bazzetta, 539 U.S. 126, 132 (2003). In evaluating the reasonableness of a prison regulation, the Court must consider four factors: (1) whether there is a “valid, rational connection between the prison regulation and the legitimate governmental interest put forward to justify it”; (2) “whether there are alternative means of exercising the right that remain open to prison inmates”; (3) “the impact accommodation . . . will have on guards and other inmates, and on the allocation of prison resources generally”; (4) whether there are “ready alternatives that could fully accommodate[ ] the prisoner’s rights at de minimis cost to valid penological interests.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 89-91 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted); Mayfield, 529 F.3d at 607 (citing Turner). The Supreme Court has recently acknowledged the importance of the first Turner factor. Beard v. Banks, 548 U.S. 521, 532 (2006) (“[T]he second, third, and fourth factors, being in a sense logically related to the Policy [at issue] itself, here add little, one way or another, to the first factor’s basic logical rationale.”). As the Supreme Court has explained, “[t]he real task . . . is not balancing these factors, but rather determining whether the Secretary [of the Department of Corrections] shows more than simply a logical relation, that is, whether he shows a reasonable relation.” Id. at 533 (emphasis 19 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 20 of 32 added); see also Morgan v. Quarterman, 570 F.3d 663, 666 (5th Cir. 2009); Mayfield, 529 F.3d at 607 (“While Turner’s standard encompasses four factors, we have noted that rationality is the controlling factor, and a court need not weigh each factor equally.”); Scott v. Miss. Dep’t of Corr., 961 F.2d 77, 80-81 (5th Cir. 1992) (“Turner [does not] require a court to weigh evenly, or even consider, each of these [four] factors. . . . Factor one is simply a restatement of the principle of rationality review: ‘[A] regulation must have a logical connection to legitimate governmental interests invoked to justify it. . . . [T]his is the controlling question . . . ; the other factors merely help a court determine if the connection is logical. . . .”). “Turner’s standard also includes a neutrality requirement- ‘the government objective must be a legitimate and neutral one . . . [and] [w]e have found it important to inquire whether prison regulations restricting inmates’ First Amendment rights operated in a neutral fashion.’” Mayfield, 529 F.3d at 607 (citing Turner, 482 U.S. at 90). As the Supreme Court has explained, “[w]here . . . prison administrators draw distinctions between publications solely on the basis of their potential implications for prison security, the regulations are ‘neutral’ in the technical sense in which we meant and used that term in Turner.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 415-16. The Supreme Court has made clear that corrections officials are to be accorded considerable deference in their prison management decisions. As the Court in Thornburgh explained: All these claims to prison access undoubtedly are legitimate; yet prison officials may well conclude that certain proposed interactions, though seemingly innocuous to laymen, have potentially significant implications for the order and security of the prison. Acknowledging the expertise of these officials and that the judiciary is “ill equipped” to deal with the difficult and delicate problems of prison management, this Court has 20 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 21 of 32 afforded considerable deference to the determinations of prison administrators who, in the interest of security, regulate the relations between prisoners and the outside world. 490 U.S. at 407-08 (emphasis added); see also Overton, 539 U.S. at 132 (“We must accord substantial deference to the professional judgment of prison administrators, who bear a significant responsibility for defining the legitimate goals of a corrections system and for determining the most appropriate means to accomplish them.”) (emphasis added). As such, the Court must apply the Turner factors, with deference to Defendants’ actions in this case. 2. Analysis The Court considers each of the Turner factors to determine whether Defendants’ censorship decisions were “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests,” with respect to Prison Masculinities, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Women Behind Bars. a. Rational Connection The first Turner factor asks whether there is a “valid, rational connection between the prison regulation and the legitimate governmental interest put forward to justify it.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 89. As noted above, this is the most important consideration. Beard, 521 U.S. at 533. PLN contends that there is no “rational reason” for censoring the books at issue in this case, particularly when compared to other publications that have not been banned, such as Mein Kampf, Lolita, The Shawshank Redemption, or Pimpology: The 48 Laws of 21 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 the Game.11 (D.E. 75 at 20-22.) Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 22 of 32 Defendants respond by explaining their reasoning behind their censorship decisions. (D.E. 82 at 14-19.) As discussed above, the TDCJ provided specific reasons for its denial of each of the books at issue. Women Behind Bars was originally disapproved due to a passage depicting “sex with a minor” on page 38 of the book, and thus would encourage “deviant criminal sexual behavior.” The specific passage at issue reads as follows: What is even more remarkable about [Tina] Thomas [a medical doctor incarcerated in Oklahoma] is that she had overcome the kind of childhood trauma that might have completely derailed her adult life. It might have been precisely that background that first propelled her to become an overachiever and attain a high level of professional success, but then came back to haunt her just as she had gotten to where she wanted to go. The dark secret of her life was that she had been forced to perform fellatio on her uncle when she was just four years old. Thomas explains that this unresolved trauma became “the template for a lifetime of distrust, fear, uncertainty, and a spirit of self-negation.” (D.E. 75-3 at 21.) Defendant Smith re-reviewed Women Behind Bars after being deposed in this lawsuit, however, and determined that TDCJ would no longer censor it, as it would not “encourage deviant criminal sexual behavior.” (D.E. 75 at 8.)12 11 Pimpology: The 48 Laws of the Game (New York: Simon Spotlight Entertainment, 2007) deals generally with the business of prostitution, and has chapter titles such as “Don’t Chase ‘Em, Replace ‘Em,” “Prey on the Weak,” “Pimp Like You’re Ho-less,” and “Get You a Bottom Bitch.” (D.E. 75-3 at 113.) 12 Defendants argue that the July 30, 2010 approval of Women Behind Bars moots PLN’s claims with respect to this publication, as there is no longer a “case or controversy.” (D.E. 82 at 17.) Plaintiff responds that, despite the approval, copies of Women Behind Bars are still not being delivered to some inmates, and that TDCJ’s censorship of this book is capable of repetition. (D.E. 90 at 17-20.) Here, the Court finds that TDCJ’s mid-litigation approval of Women Behind Bars does not moot the claims. The Supreme Court has explained that the mootness standard is “stringent,” and “[a] case might become moot if subsequent events made it absolutely clear that the allegedly wrongful behavior could not reasonably be expected to recur. The heavy burden of persuading the court that the challenged conduct cannot reasonably be expected to start up again lies with the party asserting mootness.” Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Env. Servs. (TOC), Inc., 528 U.S. 167, 189 (2000) (citations omitted); Sossamon v. Lone Star State of Texas, 560 F.3d 316, 325 (5th Cir. 2009) (citing Friends of the Earth). While “government actors in their sovereign capacity and in the exercise of their official duties are accorded a presumption of good faith” in the mootness analysis, 560 F.3d at 325, Defendants cannot demonstrate that subsequent banning of Women Behind Bars will not recur, either upon further review after this litigation concludes, or if a new edition is released. The Court declines Defendants’ invitation to dismiss Plaintiff’s claim as to Women Behind Bars on mootness grounds. 22 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 23 of 32 Perpetual Prisoner Machine was rejected for a similar reason, namely that page 45 discussed “rape,” when quoting from a 1968 Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office report discussing rape in local jails. One relevant portion of the passage reads: “virtually every slightly built young man committed to jail by the courts . . . is sexually approached within hours of his admission to prison. Many young men are overwhelmed and repeatedly ‘raped’ by gangs of inmate aggressors.” (D.E. 75, Exh. 6.) Finally, Prison Masculinities was rejected because pages 128-131 discussed “rape” and pages 194 and 222 contained “racial material.” The rape passages discuss how a prisoner was “humiliated telling anyone about” being sexually assaulted, and how he underwent “torture scenes” while incarcerated. Specifically, the relevant passages in this book discuss an inmate being “raped and beaten by Blacks as a punishment for permitting [himself] to be raped by Whites,” and that “getting fucked by a tender, gentle jock was better than the vicious gang-bangs and there was pride in making my man happy in bed . . . The s & m freaks . . . always scared the hell out of me and were the worse [sic] of all the jocks in any joint I was in.” The passages discuss repeated sexual assaults and rapes of an inmate who was a teenager at the time, some of which are quite graphic. (D.E. 75-5 at 5-9.) The racial material involves use of the phrase “damn nigger” by a corrections officer before assaulting the inmate, and a passage that states as follows: James Jackson, forty-five, who has already done seventeen and a half years of a twenty-year-to-life sentence, nods his head in agreement. Jackson continues, ‘Black people can get on the radio and use the words ‘nigger’ and ‘bitch.’ To me, that’s serious. If you think white people are going to stop us from call us niggers and bitches, you’re crazy. We’ve got to stop degrading ourselves. (D.E. 75, Ex. 29.) 23 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 24 of 32 There can be little doubt that rape and racial violence are serious problems in correctional facilities, and that prison officials’ actions are “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests” when they seek to address these problems. It is also true that rehabilitation of inmates is a “legitimate penological interest.” See O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz, 482 U.S. 342, 348 (1987) (“The limitations on the exercise of constitutional rights arise both from the fact of incarceration and from valid penological objectives – including deterrence of crime, rehabilitation of prisoners, and institutional security.”); Green v. Polunsky, 229 F.3d 486, 489 (5th Cir. 2000) (citing O’Lone). In assessing the TDCJ’s initial decision to disapprove Women Behind Bars, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Prison Masculinities, the question is not whether this Court, or indeed any outside observer, agrees with the decision that was made. Rather, the question is focused solely on whether there is a “valid, rational connection” between the decision made and a “legitimate governmental interest.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 89. With this in mind, the Court cannot say that Defendants’ disapproval decisions bear no “rational connection” to the legitimate interests of improving institutional security or assisting inmate rehabilitation. It is tempting, as Plaintiff argues, to compare the disapproved materials to others that have been approved, such as Mein Kampf, Lolita, or Pimpology. (D.E. 75.) This, however, is not the appropriate inquiry. The Court can look only at the “rationality” or “reasonableness” of the decision with respect to the particular publication at issue, keeping in mind that these decisions are made over the course of many years, perhaps by many different individuals.13 If Defendants believed that the offensive material in Women Behind Bars, Prison Masculinities, and Perpetual 13 Defendants note in their Response that many of the purported “inconsistent” books were reviewed at the TDCJ unit level, not at the DRC/MSCP level, and the decisions were made “long before any of the individual Defendants began reviewing books at TDCJ.” (D.E. 89 at 3.) 24 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 25 of 32 Prisoner Machine would interfere with legitimate penological interests, perhaps by interfering with the rehabilitation of inmates or increasing institutional violence, this decision is entitled to deference, even if subject to reasonable debate. With respect to Women Behind Bars, Defendant Weeks testified that she believed the disapproval to be justified based upon the brief reference to child sexual abuse because some of the prisoners on her unit had been sexually abused, and “sometimes just reading something can trigger a reaction. It would not be good for them. It would not be good for the unit.” Mailroom employee Michayel Smith also testified that she would disapprove Women Behind Bars. (D.E. 75-1 at 53; see also D.E. 75-2 at 374 (Michayel Smith deposition); 82-30 at 3-4.) In her declaration, Defendant Jennifer Smith explained that “a book entering into any TDCJ prison could be read by many more offenders than the offender who received the book and [her staff] often do[es] not know the background of the offender or how a publication might influence their emotional state at any given moment.” (D.E. 82-2 at 6.) She particularly notes the large number of sexual and other physical assaults in the TDCJ system in any given year, incidents which her staff must “keep in mind when reviewing books.” (D.E. 82-2 at 6; see generally D.E. 82-6 (statistics related to sexual assaults and other violence at TDCJ facilities from 20062009).) With respect to Perpetual Prisoner Machine, Defendant Smith stated in her declaration that the book should be denied “due to the amount of graphic detail describing the rape.” She explains that “[a] graphic, detailed description such as this constitutes a threat to the safety and security of the prison because offenders could ‘act out’ the description to commit a copycat type rape or it could remind an offender of a 25 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 26 of 32 similar experience which could upset the offender.” (D.E. 82-2 at 15.) This is a particular concern in light of the high number of sexual assaults at TDCJ facilities. (Id.) Finally, with respect to Prison Masculinities, Defendant Smith states in her declaration that “due to the amount of graphic detail describing rapes on pages 128-131, the book should remain on the database as denied.” (D.E. 82-2 at 17.) Just a small portion of the rape discussions in this book are reproduced above; some others are simply too graphic to include in this opinion. Defendant Smith’s determination that the graphic detail of the rape scenes could be detrimental is rational, and entitled to deference, even if others would tend to disagree with her conclusions. The Supreme Court in Thornburgh recognized the inevitable difficulty in determining whether certain materials would likely be disruptive to the prison environment, and therefore recognized that courts should defer to the decisions of prison officials. As the Court explained, “[o]nce in the prison, [incoming publications] reasonably may be expected to circulate among prisoners, with the concomitant potential for coordinated disruptive conduct. Furthermore, prisoners may observe particular material in the possession of a fellow prisoner, draw inferences about their fellow’s beliefs, sexual orientation, or gang affiliations from that material, and cause disorder by acting accordingly. . . . In the volatile prison environment, it is essential that prison officials be given broad discretion to prevent such disorder.” 490 U.S. at 412-13 (emphasis added).14 The list of TDCJ denied books submitted by Plaintiff (D.E. 75-1 at 14 It is for this reason that PLN’s various declarations (D.E. 75-4 at 46-48; 85-90; D.E. 75-5 at 47-52), submitted by authors of the publications at issue or other experts, do not change the analysis. It is not the opinions of these authors that is determinative, but rather the decisions of prison administrators, in light of their personal experience. While the declaration of former warden Ron McAndrew (D.E. 75-5 at 23-32) is somewhat more relevant (as it provides a vantage point from which to evaluate if Defendants’ decisions are in fact rational), it again misses the point. Reasonable minds can, and indeed do, differ on rational 26 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 27 of 32 145-250; D.E. 75-2 at 1-312), while long, indicated that TDCJ officials have applied their regulations consistently over time. The list of books initially denied but subsequently approved on appeal (D.E. 75-2 at 313-359) demonstrates that the TDCJ system does provide an appropriate check when a book is unreasonably denied. The lists also demonstrate the importance of deference in this case. It is likely that at least some, if not many, of the disapprovals on the list can be subject to reasonable debate and disagreement. Prison officials, however, have the authority to make these judgment calls. Given the shear numbers of books and other publications that flow through the TDCJ system on a given year, it would not be advisable (or perhaps even feasible) for the courts to make an independent judgment as to each denial, whenever called upon to do so. In making this decision, the Court does not suggest that it agrees with Defendants’ disapproval decisions, particularly in light of the minimal nature of the “offensive” material, and certain approved publications that appear to present the same problems that led to the censorship of Women Behind Bars, Prison Masculinities, and Perpetual Prisoner Machine. This, however, is not the point. The point is whether the decision is rational. Indeed, the decisions are highly subjective (as evidenced by Defendant Smith’s own about-face with respect to Women Behind Bars (D.E. 75-1 at 83)), but ultimately it is the prison administrator’s decision that is entitled to deference, not to be lightly disturbed. This Court will not substitute its own judgment for the rational (even if debatable) decisions of prison administrators. Turner, 482 U.S. at 89 (“prison administrators . . . and not the courts, [are] to make the difficult judgments concerning institutional operations.”). disapproval decisions. Indeed, Defendant Smith even changed her own mind with respect to Women Behind Bars. Mere disagreements do not demonstrate irrationality of the Defendants’ decisions. 27 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 b. Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 28 of 32 Alternative Means of Exercising The second Turner consideration is “whether there are alternative means of exercising the right that remain open to prison inmates.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. “Where ‘other avenues’ remain available for the exercise of the asserted right, courts should be particularly conscious of the ‘measure of judicial deference owed to corrections officials . . . in gauging the validity of the regulation.’” Id. PLN contends that, as a small non-profit organization, it can only communicate with inmates through the mail. (D.E. 75 at 22.) Defendants respond that TDCJ inmates have a “vast number” of approved books from which to chose, a total of approximately 80,000 approved titles. TDCJ has also approved “almost all” of PLN’s books for receipt by prisoners. (D.E. 82 at 16-17.) PLN’s argument on this factor appears more related to its own ability to exercise its rights, rather than the rights of prison inmates. The focus, however, is upon whether the inmates themselves have other ways to receive the information at issue. PLN has not demonstrated that TDCJ regulations, as applied, significantly inhibit TDCJ inmate’s rights to receive information. Indeed, with over 80,000 approved titles, it is difficult to argue that prisoners lack “alternative means” of exercising their rights. In any event, the Court concludes that PLN has plenty of ways to interact with prisoners. Defendant Smith states in her declaration that, of the 46 books listed at PLN’s website, only three are currently denied, and 37 have been approved. (D.E. 82-2 at 18.) PLN does not dispute this tally. The second factor does not favor PLN. 28 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 c. Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 29 of 32 Impact of Accommodation The third Turner factor considers “the impact accommodation of the asserted constitutional right will have on guards and other inmates, and on the allocation of prison resources generally.” 482 U.S. at 90. PLN contends that adding its books to the permissible reading list cannot have more than a de minimis impact, as evidenced by some of the other books that have been approved, and the fact that the same books have been received at other TDCJ units. (D.E. 75.) This factor, though less important, favors PLN. In light of the numerous publications already at issue, there is no indication that accommodation would impose increase costs upon the TDCJ. Nevertheless, as the Court has already concluded that Defendants’ application of the TDCJ policies in this case is rationally related to a legitimate governmental interest in limiting institutional violation and aiding rehabilitation, the mere ease of accommodation does not change the outcome. d. Ready Alternatives The final Turner factor examines whether there are “ready alternatives that could fully accommodate[ ] the prisoner’s rights at de minimis cost to valid penological interests.” As the Supreme Court explained, “the absence of ready alternatives is evidence of the reasonableness of a prison regulation.” 482 U.S. at 91. If an inmate can point to such an alternative, “a court may consider that as evidence that the regulation does not satisfy the reasonable relationship standard.” Id. PLN does not present an argument on this final factor. As both sides admit, there are over 80,000 approved titles from which inmates may choose. Some of these titles, such as Lolita, The Shawshank Redemption, or Mein 29 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 30 of 32 Kampf contain similar objectionable material that led TDCJ to disapprove the books at issue in this litigation. Nonetheless, short of banning all books with any type of objectionable material (which neither side suggests), alternative reading materials will continue to be available at TDCJ facilities. The mere fact that alternatives exist does not alter the Court’s conclusion as to the overall reasonableness of Defendant’s application of the regulations at issue. e. Neutrality A final important consideration under Turner is the neutrality of the state action at issue. Mayfield, 529 F.3d at 607 (“we have found it important to inquire whether prison regulations restricting inmates’ First Amendment rights operated in a neutral fashion.’”) (citing Turner, 482 U.S. at 90). PLN does not specifically argue that the regulations at issue have been applied in a non-neutral, biased fashion, though the Court must consider this possibility. As noted above, of the 46 books listed at PLN’s website, only three are currently denied, and 37 have been approved. (D.E. 82-2 at 18.) Smith also states that TDCJ offenders have more than 80,000 approved books from which to choose. (D.E. 822 at 19.) Available statistics for 2008 demonstrate that of 3,158 publications reviewed by the MSCP, 2,370 were reviewed and approved, with only 788 denied, an approval rate of approximately 75 % at the MSCP level. (D.E. 82-5 at 16; see generally D.E. 82-5 (statistics related to approvals and denials of publications in 2008); D.E. 82-25 (PLN booklist).). There is thus no evidence of bias against books distributed by PLN specifically, or any particularly genre (other than those allowed to be restricted under current TDCJ regulations). The neutrality factor is therefore satisfied. 30 / 32 Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 E. Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 31 of 32 Summary In light of the foregoing, the Court concludes that PLN has not met its burden to prove that Defendant’s application of the TDCJ regulations to Women Behind Bars, Perpetual Prisoner Machine, and Prison Masculinities, is not “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.” As such, PLN has not demonstrated that Defendants have violated its First Amendment rights. In light of this conclusion, the Court need not address Defendants’ arguments regarding qualified immunity, lack of personal involvement, punitive damages, injunctive relief, and declaratory relief. (D.E. 82 at 2025.) Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment also addresses its due process cause of action. (D.E. 75 at 23-26.) As noted above, the Court already dismissed this cause of action with respect to the individual capacity claims against Defendants. (D.E. 53; D.E. 66.) To the extent Plaintiff continues to pursue this claim against Defendant Livingston in his official capacity, the Court dismisses this claim. The Court finds that the February 2010 amendments to TDCJ regulation BP-03.91 satisfies PLN’s due process concerns. The regulations now provide, “[i]f a publication is rejected, the offender and sender shall be provided a written notice of the disapproval and a statement of the reason for disapproval within 72 hours of receipt of the publication on a Publication Denial Form. Within the same time period, the offender and sender shall be notified of the procedure for appeal. . . . The offender or sender may appeal the rejection of the publication through procedures provided by these rules.” (D.E. 75-1 at 120 (emphasis added).) The revisions also provide that “[a]ny . . . sender of a publication may appeal the rejection of any correspondence or publication.” 31 / 32 (D.E. 75-1 at 122.) The Supreme Court in Case 2:09-cv-00296 Document 96 Filed in TXSD on 01/04/11 Page 32 of 32 Procunier stated, with respect to senders of correspondence, the sender must “be given a reasonable opportunity to protest that decision, and [have] complaints be referred to a prison official other than the person who originally disapproved the correspondence.” Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396, 418-19 (1974); see also Guajardo v. Estelle, 580 F.2d 748, 762 n.10 (5th Cir. 1978). The current TDCJ regulations meet this standard.15 Thus, the Court must therefore deny Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 75) and grant Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 82).16 V. Conclusion For the reasons stated above, the Court DENIES Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 75) and GRANTS Defendants’ Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. 82). SIGNED and ORDERED this 4th day of January, 2011. ___________________________________ Janis Graham Jack United States District Judge 15 As the due process claim is maintained, if at all, solely against Defendant Livingston in his official capacity, “the relief sought must be declaratory or injunctive in nature and prospective in effect.” See Aguilar v. Texas Dept. of Criminal Justice, 160 F.3d 1052, 1054 (5th Cir. 1998). As the TDCJ policy has already been altered, and the Court find it is now consistent with due process requirements, PLN cannot seek any further relief, and this claim must be dismissed. 16 The Court also DENIES AS MOOT Defendants’ Motion to Exclude Expert Opinion, (D.E. 76) in light of its dismissal of this action. 32 / 32