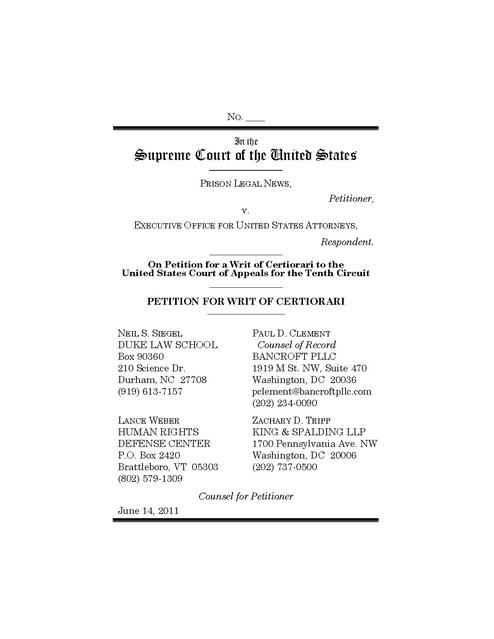

Prison Legal News v. EOUSA, US, Petition, public records, 2010

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.