Amicus Curiae Brief in the US Supreme Court for PLN Advertisers

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

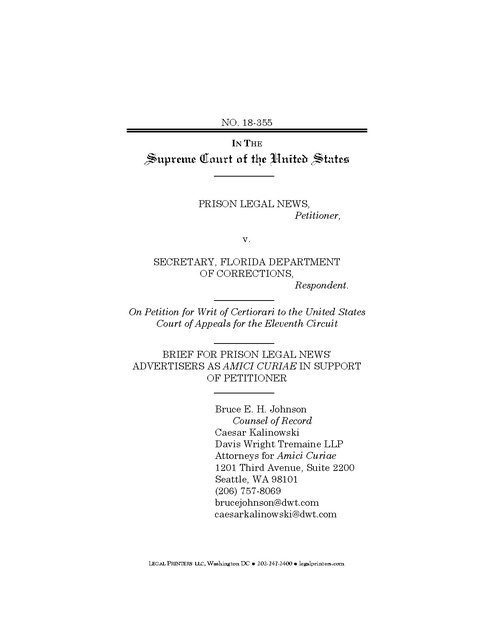

NO. 18-355 IN THE PRISON LEGAL NEWS, Petitioner, v. SECRETARY, FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, Respondent. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit BRIEF FOR PRISON LEGAL NEWS’ ADVERTISERS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER Bruce E. H. Johnson Counsel of Record Caesar Kalinowski Davis Wright Tremaine LLP Attorneys for Amici Curiae 1201 Third Avenue, Suite 2200 Seattle, WA 98101 (206) 757-8069 brucejohnson@dwt.com caesarkalinowski@dwt.com LEGAL PRINTERS LLC, Washington DC ! 202-747-2400 ! legalprinters.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE ............................ 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................. 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................ 3 I. Florida’s Suppression of Free Speech in the Prison Context Is Unconstitutional Because It Is Not Reasonably Related to Neutral Penological Objectives ........................................ 7 A. Florida’s Regulations and Their Application Are Overbroad, Arbitrary, Underinclusive, and Only Remotely or Indirectly Related to Its Avowed Objectives....................................................... 8 1. Florida’s regulations are overbroad ........ 9 2. Florida’s regulations are arbitrary ........ 11 3. Florida’s regulations are underinclusive ........................................ 13 4. Florida’s regulations are too remote and attenuated from their purported objectives ................................................ 15 B. Florida’s Avowed Penological Objectives Are Not Neutral in this Context ................. 17 i II. Affirming the Eleventh Circuit’s Suppression of First Amendment Rights in this Context Is Inconsistent with Other Circuits and Would Lead to Absurd Results .................................... 18 CONCLUSION ....................................................... 20 APPENDIX (DESCRIPTIONS OF AMICI CURIAE) .......................................................... A-1 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Ahlers v. Rabinowitz, 684 F.3d 53 (2d Cir. 2012) ...................................19 Aikens v. Jenkins, 534 F.2d 751 (7th Cir. 1976)................................13 Allen v. Coughlin, 64 F.3d 77 (2d Cir. 1995) .....................................13 Amatel v. Reno, 156 F.3d 192 (D.C. Cir. 1998) ..............................19 Ashker v. California Dep’t of Corr., 350 F.3d 917 (9th Cir. 2003)..................................9 Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963)..................................................2 Beard v. Banks, 548 U.S. 521 (2006)................................................5 Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809 (1975)................................................4 Clement v. Cal. Dep’t of Corr., 364 F.3d 1148 (9th Cir. 2004)......................3, 9, 10 Crime Justice & Am., Inc. v. Honea, 876 F.3d 966 (9th Cir. 2017)................................17 iii Crofton v. Roe, 170 F.3d 957 (9th Cir. 1999).................... 10, 11, 12 Edenfield v. Fane, 507 U.S. 761 (1993)................................................2 Gregory v. Auger, 768 F.2d 287 (8th Cir. 1985)................................19 Griffin v. Lombardi, 946 F.2d 604 (8th Cir. 1991)............................8, 19 Jacklovich v. Simmons, 392 F.3d 420 (10th Cir. 2004)................................9 Jackson v. Pollard, 208 F. App’x 457 (7th Cir. 2006) .........................14 Lindell v. Frank, 377 F.3d 655 (7th Cir. 2004)..........................10, 11 Manual Enterprises, Inc. v. Day, 370 U.S. 478 (1962)................................................4 Martucci v. Johnson, 944 F.2d 291 (6th Cir. 1991)................................19 Morrison v. Hall, 261 F.3d 896 (9th Cir. 2001)................................11 Muhammad v. Pitcher, 35 F.3d 1081 (6th Cir. 1994)..........................12, 14 Murphy v. Missouri Dep’t of Corr., 814 F.2d 1252 (8th Cir. 1987)........................10, 11 iv Nasir v. Morgan, 350 F.3d 366 (3d Cir. 2003) .................................16 Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817 (1974)..........................................4, 21 Pepperling v. Crist, 678 F.2d 787 (9th Cir. 1982)................................10 Perry v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corr., 664 F.3d 1359 (11th Cir. 2011)..............................4 Pitt News v. Pappert, 379 F.3d 96 (3d Cir. 2004) ......................... 4, 15, 16 Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145 (9th Cir. 2001)..............................12 Prison Legal News v. Lehman, 397 F.3d 692 (9th Cir. 2005)................................15 Prison Legal News v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corr., 890 F.3d 954 (11th Cir. 2018)...................... passim Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974)...................................... passim Ramirez v. Pugh, 379 F.3d 122 (3d Cir. 2004) ...........................10, 11 Rowe v. Shake, 196 F.3d 778 (7th Cir. 1999)................................19 v Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. Members of New York State Crime Victims Bd., 502 U.S. 105 (1991)................................................4 Sutton v. Rasheed, 323 F.3d 236 (3d Cir. 2003) .................................13 Thongvanh v. Thalacker, 17 F.3d 256 (8th Cir. 1994)..................................12 Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401 (1989)...................................... passim Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78 (1987)........................................ passim Constitutional Provisions U.S. Constitution, First Amendment ............... passim Codes Florida Administrative Code 33501.401(3) .............................................................10 Florida Administrative Code 33501.401(3)(l) .................................................6, 8, 12 Florida Administrative Code 33501.401(3)(m) ...............................................6, 8, 13 Rules Supreme Court Rule 37.6 ...........................................1 vi INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE 1 Prison Legal News is an award-winning monthly publication that focuses on prisoners and content related to prisons, prison reform, and legal issues. Sometimes critical in its reporting on prisons and prisoner abuses, the publication is disfavored by many prison administrations and has often been forced to vindicate its First Amendment rights in court. Prison Legal News is funded by advertisements, which are purchased by law firms, human rights organizations, and other persons and organizations offering prison-related services. Amici are comprised of many of those advertisers, and seek to vindicate Petitioner’s, and their own, First Amendment rights. Amici believe that this case presents an opportunity for this Court to vindicate the right to free speech—an essential and explicit part of the liberty guaranteed by the First Amendment— against arbitrary government suppression, where the State of Florida has sought to dramatically curtail the rights of a disfavored population. We urge this Court to grant certiorari to protect Petitioner’s free speech rights, as well as the attendant rights of Prison Legal News’ advertisers and incarcerated readers. 1 Pursuant to Rule 37.6, amici affirm that no counsel for any party authored this brief in whole or in part. Further, no person other than amici, its members, or its counsel made a monetary contribution to fund its preparation or submission. Both parties were notified and have consented to the filing of this brief. 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT “Any system of prior restraints of expression comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity.” Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58, 70 (1963). So when a state government tramples the constitutionally protected speech rights of a disfavored group— especially in favor of arbitrary regulations and remotely related objectives—this Court rightfully should be skeptical. Otherwise, we risk crushing fundamental and enumerated rights “in a headlong rush to strip inmates of all but a vestige of free communication with the world beyond the prison gate.” Thornburgh v. Abbott, 490 U.S. 401, 422 (1989) (Stevens, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part). It is beyond argument that Petitioner Prison Legal News (“PLN”), its contributing writers, and its advertisers have a First Amendment right to reach prisoners with their speech. See Edenfield v. Fane, 507 U.S. 761, 765 (1993). Here, however, the Eleventh Circuit eviscerated those constitutional rights. Based on nothing more than total deference to prison administrators’ self-serving statements, the court upheld the Florida Department of Corrections’ (“FDOC”) absurdly broad ban on all issues of Prison Legal News. See Prison Legal News v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corr., 890 F.3d 954, 975 (11th Cir. 2018). Although “this Court has afforded considerable deference to the determinations of prison administrators who . . . regulate the relations between prisoners and the outside world,” 2 Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 408, a prison regulation that suppresses speech must still be “‘reasonably related’ to legitimate penological objectives” to be constitutional. Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 87 (1987). Unlike here, other circuits have struck down similar bans when the regulation, its objectives, or its application are overbroad, arbitrary, remote or speculative, underinclusive, or unrelated to penological goals. See Clement v. Cal. Dep’t of Corr., 364 F.3d 1148, 1152 (9th Cir. 2004). Because FDOC’s regulations suppressing PLN’s freedom of speech are all of those, and upholding them would lead to absurd results, this Court should grant PLN’s petition, reverse the Eleventh Circuit, and vindicate the First Amendment. ARGUMENT “[T]here is no question that publishers who wish to communicate with [subscribing prisoners] . . . have a legitimate First Amendment interest in access to prisoners.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 408.2 “[S]ensitive to the delicate balance that prison administrators must strike between the order and security of the internal prison environment and the legitimate demands of those on the ‘outside’ who seek to enter that environment,” id. at 407, this constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech and press “assures the maintenance of our political 2 “Access is essential to lawyers and legal assistants representing prisoner clients . . . [and] to journalists seeking information about prison conditions[.]” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 407 (emphasis added). 3 system and an open society, . . . and secures the paramount public interest in a free flow of information to the people concerning public officials,” Pell v. Procunier, 417 U.S. 817, 832 (1974) (internal citations and quotations omitted). A publication’s advertisements are also unquestionably protected by the First Amendment. Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809, 818 (1975) (“[S]peech is not stripped of First Amendment protection merely because it appears in [paid commercial advertisements].”). And advertisers’ “First Amendment right to access inmates give[s them] a liberty interest in seeing that their advertisements reach the inmates.” Perry v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corr., 664 F.3d 1359, 1367–68 (11th Cir. 2011). In fact, an advertiser’s free speech rights are often bound with its publisher’s because imposing content-related restrictions on advertisements “establishes a financial disincentive to create or publish works with [that] particular content.” See Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. Members of N.Y. State Crime Victims Bd., 502 U.S. 105, 118 (1991).3 3 PLN avers that it has lost advertisers as a result of FDOC’s regulations because those groups cannot reach their key demographic. Therefore, allowing a publication to be targeted through its advertising revenue in this case implicates both groups’ First Amendment rights. See also Pitt News v. Pappert, 379 F.3d 96, 106 (3d Cir. 2004) (“If government were free to suppress disfavored speech by preventing potential speakers from being paid, there would not be much left of the First Amendment.”); Manual Enters., Inc. v. Day, 370 U.S. 478, 493 (1962) (“Since publishers cannot practicably be expected to investigate each of their advertisers, and since the economic 4 In the prison context (like here), administrators are shown deference in creating security and rehabilitation-related regulations that may infringe on constitutional rights. Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 408. That deference, while considerable, is not insurmountable. As this Court stated in Turner, “[p]rison walls do not form a barrier separating prison inmates from the protections of the Constitution.” 482 U.S. at 84. To determine if deference should be afforded to a specific regulation, however, “we must determine whether the governmental objective underlying the regulations at issue is legitimate and neutral, and that the regulations are rationally related to that objective.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 87; Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 414 (adopting the Turner standard in incoming prison mail First Amendment challenges). Prison authorities are required “to show more than a formalistic logical connection between a regulation and a penological objective.” Beard v. Banks, 548 U.S. 521, 535 (2006). Instead, they must show “a reasonable relationship” that is not “so remote as to render the policy arbitrary or irrational,” Turner, 482 U.S. at 89–90, in light of the “importance of the rights at issue,” Banks, 548 U.S. at 533. consequences of an order barring even a periodical from the mails might entail heavy a magazine publisher might refrain advertisements from those whose own conceivably be deemed objectionable[.]”). 5 single issue of a financial sacrifice, from accepting materials could Here, Florida requires a publication to be impounded if it contains an advertisement that is the focus of the publication, or is “prominent or prevalent throughout the publication,” and promotes three-way calling services, pen pal services, the purchase of products or services with postage stamps, or conducting a business in prison. Fla. Admin. Code R. (“Code”) 33-501.401(3)(l). Likewise, an entire publication may be impounded if a single advertisement “presents a threat to the security, order or rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person.” Code 33501.401(3)(m). FDOC contends that these regulations relate to “prison security and public safety” objectives because prisoners could use the prohibited services to “harass the general public,” “open doors to criminal activity,” “solicit[] kind-hearted but gullible people and then defraud[] them,” “us[e] their stamps as a currency in the underground prison economy,” and “arrange contraband smuggling” on the outside. Prison Legal News, 890 F.3d at 975, 958–59. PLN now challenges the Eleventh Circuit’s decision to uphold FDOC’s practice of impounding PLN’s flagship publication directed to inmates, Prison Legal News. Since 2009, FDOC has enforced its prohibition based on its claim that the publication contains certain types of “problematic” advertising that are “prominent or prevalent throughout the publication.” See Code 33-501.401(3)(l). Because the Eleventh Circuit’s holding was overly deferential to FDOC in ruling that its regulation was reasonably 6 related to legitimate penological interests, it conflicts with other circuits’ jurisprudence and leads to absurd results. This Court should grant certiorari to resolve those inconsistencies, clarify the law, and vindicate PLN’s constitutional rights. I. Florida’s Suppression of Free Speech in the Prison Context Is Unconstitutional Because It Is Not Reasonably Related to Neutral Penological Objectives In order to survive PLN’s challenge, FDOC is required to show that its regulation suppressing all of PLN and its advertisers’ speech—including acceptable and objectionable portions—is (1) reasonably and rationally related to a (2) legitimate, (3) neutral, (4) penological objective, and not an (5) arbitrary, irrational, or an exaggerated response. It cannot do so. Here, FDOC’s regulation results in the total prohibition of one publication’s legal articles, legal services advertising, and “objectionable” advertisements that promote entirely benign and lawful services. Because the deprivation of rights here is so severe and FDOC’s reasons are so attenuated and arbitrary, FDOC cannot meet its legal burden to validate its unconstitutional suppression of speech. Furthermore, because the Eleventh Circuit’s decision is inconsistent with other circuits’ First Amendment prison jurisprudence, this Court should grant certiorari. 7 A. Florida’s Regulations and Their Application Are Overbroad, Arbitrary, Underinclusive, and Only Remotely or Indirectly Related to Its Avowed Objectives FDOC’s regulations are inherently arbitrary, arbitrary as applied, overbroad, underinclusive, and are not reasonably related to the proffered objectives of the government. This Court and the circuit courts have provided guidance as to whether a regulation is reasonably or arbitrarily related to an objective. In Procunier v. Martinez, 416 U.S. 396 (1974), for example, this Court held that “outgoing personal correspondence from prisoners-did not, by its very nature, pose a serious threat to prison order and security” and therefore was not related to the defendant’s objectives. Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 411. But the reasonableness of the regulation has been examined in other terms, including where the regulation or its application is overbroad, arbitrary, underinclusive, remote or speculative, or unrelated to a penological objective. The regulations at issue in this case, Codes 33501.401(3)(l), (m), are all of the above: unreasonably overbroad, arbitrary, underinclusive, too remote and speculative to be related, and only indirectly related at best to penological objectives. That FDOC’s regulation stands alone amongst the nation’s prisons for its unconstitutional policy should signal as much. See Griffin v. Lombardi, 946 F.2d 604, 608 (8th Cir. 1991) (“We can only say that the conflict between the policies described in the affidavits ultimately filed by 8 prison officials, and the practices followed with respect to other inmates and at other penitentiaries, should give the officials some pause.”). In light of the cases below, this Court should resolve the inconsistencies created by the Eleventh Circuit and hold that Codes 33-501.401(3)(l), (m) fail to meet the standard for the first Turner factor.4 1. Florida’s regulations are overbroad Overbroad regulations are not reasonably related to government objectives because they prohibit or censor more constitutionally protected materials than necessary. See Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 412 (commenting on Martinez and stating that “the regulations at issue were broader than ‘generally necessary’ to protect the interests at stake”). Rejecting the government’s argument that “a fourmonth complete denial of access to constitutionally protected materials (regardless of behavior) furthers behavior management or rehabilitation,” the Tenth Circuit in Jacklovich v. Simmons also based its decision in part on the inadequacy of relationship evidence and the availability of other reading material. 392 F.3d 420, 429 (10th Cir. 2004). Similarly, the Ninth Circuit in Clement held that “security concerns” regarding coded messages were overbroad and not sufficiently related to a 4 See Ashker v. Cal. Dep’t of Corr., 350 F.3d 917, 922 (9th Cir. 2003) (“[I]f the prison fails to show that the regulation is rationally related to a legitimate penological objective, we do not consider the other factors.”). 9 prohibition of all internet-generated mail. 364 F.3d at 1152.5 The regulations here are entirely overbroad and this Court should presume them unconstitutional. Pepperling v. Crist, 678 F.2d 787, 791 (9th Cir. 1982) (“[T]he blanket prohibition against receipt of the publications by any prisoner carries a heavy presumption of unconstitutionality.”). FDOC’s regulations mandate that the entirety of Prison Legal News be impounded if an issue contains one or more offending advertisements. Code 33-501.401(3). So along with allegedly objectionable material (which is still protected by the First Amendment), the regulations drag down and censor important legal and prisonrelated information contained in Prison Legal News articles. 5 See also Lindell v. Frank, 377 F.3d 655, 660 (7th Cir. 2004) (holding that a ban on all newspaper clippings was overbroad); Ramirez v. Pugh, 379 F.3d 122, 128 (3d Cir. 2004) (refuting “that rehabilitation legitimately includes the promotion of ‘values,’ broadly defined, with no particularized identification of an existing harm towards which the rehabilitative efforts are addressed”); Crofton v. Roe, 170 F.3d 957, 960 (9th Cir. 1999) (rejecting blanket ban on the receipt of all gift publications because prison regulations already demanded that publications originate with the publisher); Murphy v. Mo. Dep’t of Corr., 814 F.2d 1252, 1256 (8th Cir. 1987) (accepting the government’s contention that Aryan literature is “a clear and present danger to security of the prison,” but holding “that a total ban is too restrictive a mail censorship policy”). 10 What’s more, non-offending or innocuous advertisements of all kinds are also suppressed regardless of whether they promote or harm prison objectives. Lawyers and civil rights organizations seeking to inform prisoners of their rights have their content blocked because they happen to appear in a publication that advertises three-way calling. Articles informing prisoners of important Supreme Court cases are suppressed because pen pal services have been advertised. Because there is no federal constitutional right to counsel in federal habeas proceedings (something routinely advertised in the publication), the regulation effectively disenfranchises and blocks a disfavored group from accessing legal assistance. Like banning all newspaper clippings, Lindell, 377 F.3d at 660, or all gift publications, Crofton, 170 F.3d at 960, “a total ban is too restrictive a mail censorship policy” to be constitutional in this instance. Murphy, 814 F.2d at 1256. 2. Florida’s regulations are arbitrary When the government’s objectives or regulations are arbitrary, irrational, or simply unrelated to a penological interest, courts are invited to reject them because they invite “prison officials and employees to apply their own personal prejudices and opinions as standards for prisoner mail censorship.” Martinez, 416 U.S. at 415. See also Ramirez v. Pugh, 379 F.3d 122, 128 (3d Cir. 2004) (rejecting a regulation that makes “prisoners’ First Amendment rights . . . subject to the pleasure of their custodians”); Morrison v. Hall, 261 F.3d 896, 902–04 (9th Cir. 11 2001) (holding that “prohibiting inmates from receiving mail based on the postage rate at which the mail was sent is an arbitrary means of achieving the goal of volume control”); Prison Legal News v. Cook, 238 F.3d 1145, 1149–50 (9th Cir. 2001) (holding that “tying the receipt of subscription nonprofit newsletters to postal service rate classifications” is arbitrary because that does not promote security or relate to penological concerns).6 Like those other cases, the regulations here and their application to Prison Legal News are entirely arbitrary, focusing their ire on random services. Most arbitrary, however, is the broad latitude and powers of prison staff to apply the rules in disparate and discriminatory ways, determining if (1) “the advertisement is the focus of, rather than being incidental to, the publication,” Code 33-501.401(3)(l), (2) “the advertising is prominent or prevalent throughout the publication,” id., or (3) “otherwise presents a threat to the security, order or 6 See also Muhammad, 35 F.3d at 1085 (treating legal mail from the Attorney General’s Office differently than “legal mail from private attorneys, courts, and legal assistance organizations” is arbitrary); Crofton, 170 F.3d at 960 (blanket ban on the receipt of all gift publications is unrelated to penological interests because “[t]he issue is not whether an overall restriction on other gift items is legitimate. . . . the issue is whether there is a penological justification for the restriction on First Amendment rights”); Thongvanh v. Thalacker, 17 F.3d 256, 259 (8th Cir. 1994) (“English only” correspondence rule was arbitrarily applied because languages other than Lao were permitted, and blocking certain languages is not reasonably related to a legitimate government interest). 12 rehabilitative objectives of the correctional system or the safety of any person,” Code 33-501.401(3)(m). This type of expansive, vague guidance gives government employees unfettered control over prisoners’ First Amendment rights, “invit[ing] prison officials and employees to apply their own personal prejudices and opinions as standards for prisoner mail censorship.” Martinez, 416 U.S. at 415. See Aikens v. Jenkins, 534 F.2d 751, 756–57 (7th Cir. 1976) (invalidating a regulation that generally prohibits publications that are “in any way subversive of institutional discipline”). Moreover, it permits censorship of writings that “unduly complain” about prison issues and thus “present[] a threat to the [undefined] security, order or rehabilitative objectives,” as determined by the sole discretion of the prison officials. See Martinez, 416 U.S. at 415. Neither this Court nor any other circuit courts have applied such broad deference to decidedly discretionary suppression of speech. 3. Florida’s regulations are underinclusive Underinclusive regulations are often considered unreasonable, especially when they ignore “the existence of obvious, easy alternatives[.]” Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. In Sutton v. Rasheed, the Third Circuit found it difficult “to discern a legitimate penological interest in the denial of Nation of Islam texts” when the prison allowed other religious texts. 323 F.3d 236, 254 (3d Cir. 2003). See also Allen v. Coughlin, 64 F.3d 77, 80 (2d Cir. 1995) (rejecting ban on newspaper clippings because the prison already 13 allowed full newspapers); Muhammad v. Pitcher, 35 F.3d 1081, 1085 (6th Cir. 1994) (rejecting mail policy that only applied to one type of legal mail); Jackson v. Pollard, 208 F. App’x 457, 461 (7th Cir. 2006) (rejecting a prohibition on the “delivery of printed email responses” because “inmates may freely influence the public by soliciting and receiving from the public handwritten responses”). The regulations here are as underinclusive as they are overbroad. See Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. Three-way calling advertisements are penalized, but calling cellphones (which permit three-way calling) is not. Pen pal service advertisements are prohibited, yet the services themselves, as well as having or writing to pen pals, are not. Cash-forstamps advertisements are prohibited, but stamps are still made available despite the prison knowing they will be used for currency. Business assistance service advertisements are objectionable, yet finding employment and gaining job skills is a critical part of rehabilitative efforts. Effectively, FDOC’s policy targets speech in the form of advertisements, punishes that speech and any associated speech, and then continues to ignore other ways that the objectives are circumvented. Thus, prisoners continue to have a plethora of means to “harass the general public,” defraud “kindhearted but gullible people,” “arrange contraband smuggling,” and “us[e] their stamps as a currency in the underground prison economy.” Prison Legal News, 890 F.3d at 958–59. Had the FDOC felt the services offered in these advertisements were so 14 detrimental to prison security as to require a total ban on publications featuring them, it entirely missed more obvious and less restrictive means that did not require trampling PLN or its advertisers’ First Amendment rights. 4. Florida’s regulations are too remote and attenuated from their purported objectives A regulation’s relation to an objective can also be unreasonable when it is too remote or attenuated. See Turner, 482 U.S. at 89–90 (stating that a regulation cannot stand if “the logical connection between the regulation and asserted goal is so remote as to render the policy arbitrary or irrational”). In Pitt News, the Third Circuit examined whether alcohol venders could be banned from placing advertisements with “those media affiliated with [public] educational institutions[.]” 379 F.3d at 107 (Alito, J.). Holding that the advertisers’ First Amendment rights had been violated (in an admittedly non-prison context), the court stated that “[i]n contending that underage and abusive drinking will fall if alcoholic beverage ads are eliminated . . ., the Commonwealth relies on nothing more than ‘speculation’ and ‘conjecture.’” Id. at 107–08. See also Prison Legal News v. Lehman, 397 F.3d 692, 695–96 (9th Cir. 2005) (striking down a Washington regulation that prohibited receipt of “non-subscription bulk mail and catalogs” because no one had ever tried to “flood” a prison with publications). 15 Like the government’s reasons for prohibiting the advertisements in Pitt News, FDOC’s reasons for suppressing speech are also too remotely related to its objectives to be reasonable. See 379 F.3d at 107– 08. Invoking “prison security and public safety” goals, FDOC asserts that there is a logical connection between the regulations and its penological goals. Not so. Unlike other constitutional suppressions of the First Amendment in the prison context, none of the “objectionable” advertisements here pose a direct threat to anyone—much less prisoners or staff. Accord Nasir v. Morgan, 350 F.3d 366, 372 (3d Cir. 2003) (regulation that prohibits correspondence between current and former inmates related to objectives because letters could contain escape-related information or threats). In fact, the only real connection between stopping these advertisements from reaching prisoners and penological objectives is an indirect one, speculative and remote. To accept FDOC’s rationale, this Court would have to assume that a prisoner might (1) subscribe to an otherwise unobjectionable publication, (2) see an advertisement for one of these lawful-but-problematic services, (3) call the service, (4) pay or otherwise secure funds for the service itself, and (5) misuse the service (6) in a way that could affect the prison’s safety and security. Surely the connection between the regulations and objectives must be more closely linked to permit the suppression of PLN’s free speech for years on end. 16 B. Florida’s Avowed Penological Objectives Are Not Neutral in this Context This Court mandates that “the governmental objective . . . be a legitimate and neutral one.” Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. “PLN does not dispute that the [FDOC’s] asserted interests for the impoundments—prison security and public safety— are legitimate.” Prison Legal News, 890 F.3d at 967. “Neutrality,” this Court has said, also means “the regulation or practice in question must further an important or substantial governmental interest unrelated to the suppression of expression,” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 415 (quoting Martinez, 416 U.S. at 413). See Crime Justice & Am., Inc. v. Honea, 876 F.3d 966, 978 n.2 (9th Cir. 2017) (finding the regulation neutral because it did not distinguish between content, but rather between manner of solicitation). Invoking the talismanic phrase “safety and security” does not relieve FDOC of all duty to respect PLN, its advertisers, or prisoners’ free speech rights. While those oft-repeated objectives are legitimate and facially neutral, see Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 415, the regulations must further those objectives “in a neutral fashion, without regard to the content of the expression,” Turner, 482 U.S. at 90. As previously discussed, the regulations are not reasonably related and therefore cannot “further an important or substantial governmental interest unrelated to the suppression of expression.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 415 (quoting Martinez, 416 U.S. at 413). 17 Additionally, because these regulations can (and are) arbitrarily applied, their application necessarily is biased as to fulfilling FDOC’s objectives. Prison officials are free to interpret the prominence, prevalence, or threat of advertisements in ways that discriminate against disfavored or critical content. That the regulations target the prisoners’ ability to communicate (with otherwise permissible services and lawyers) by prohibiting a specific type of speech (commercial advertisements), which are displayed in a constitutionally protected medium (a prison and law-related publication), to the detriment of other unobjectionable speech (the entirety of Prison Legal News and its other advertisers), conveys an illicit relationship between FDOC’s true objectives and its unconstitutional suppression of free speech. II. Affirming the Eleventh Circuit’s Suppression of First Amendment Rights in this Context Is Inconsistent with Other Circuits and Would Lead to Absurd Results In practical terms, FDOC’s regulations and its prohibition of Prison Legal News are extremely severe and if permitted, would lead to an absurd neutering of the First Amendment in the prison context. From 2009 through 2014, FDOC impounded 100 percent of all Prison Legal News issues, unconstitutionally providing notice only 42 percent of the time. See Prison Legal News, 890 F.3d at 977. FDOC’s justification: prison security and public safety related to the harassment or defrauding of people outside of prison, and the prevention of criminal activity. Based on these facts, not only does 18 FDOC’s policy depart from the rest of the country’s prisons and courts’ jurisprudence, see Griffin, 946 F.2d at 608, but it also illuminates the path for other prisons to cut off disfavored publishers from subscribing prisoners and the protections afforded by the First Amendment. No other circuit has ever upheld a regulation that applies such a broad sweeping ban on free speech. Normally, permissible constitutional suppressions of speech involve direct threats to prison safety and security, Martucci v. Johnson, 944 F.2d 291, 296 (6th Cir. 1991) (upholding regulation that withheld “mail destined for a prisoner believed to be planning an escape”), or crime-specific rehabilitation efforts, Ahlers v. Rabinowitz, 684 F.3d 53, 64 (2d Cir. 2012) (affirming prohibition on sexually explicit material from a civilly committed sex offender); Amatel v. Reno, 156 F.3d 192, 199 (D.C. Cir. 1998) (sexually explicit material), and are short in duration or scope, Rowe v. Shake, 196 F.3d 778, 782 (7th Cir. 1999) (permitting prohibitions that “were relatively shortterm and sporadic”); Gregory v. Auger, 768 F.2d 287, 290 (8th Cir. 1985) (same). Conversely in this case, the speech being targeted is not hate speech nor does it represent a direct threat to anyone at the prison. It is not linked to a specific rehabilitative effort but instead prohibits access to an entire publication to preclude viewing advertisements for “problematic” services. And most shockingly, the regulations’ duration is much longer than those that have been upheld in other circuits. To this day, PLN’s advertisers still cannot reach 19 their audience. Affirming the Eleventh Circuit, then, would mean upholding a lengthy, indiscriminately expansive bar on advertisements (of perfectly lawful services) on the ground that it will indirectly help prison goals. Upholding FDOC’s regulation also means opening the door for prisons to suppress any and all incoming mail or publications, removing any vestige of First Amendment rights in the prison context. All that would be necessary, at least in the Eleventh Circuit’s view, is for prisons to ban incoming speech and invoke an indirect—yet admirable—penological objective. Language books could be banned because they enable prisoners to learn a means of communication that guards cannot understand. The Bible could be banned because it contains violent stories, ostensibly leading to more violent prison confrontations. Case law books could be banned because they recount gruesome crimes or stoke prisoners’ animosity towards the legal system. Effectively, no written work could make its way through prison bars so long as some portion of that work included otherwise perfectly legal speech deemed by a prison official to be “prevalent” and “detrimental.” The First Amendment’s guarantee that the government “shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press” simply demands more. CONCLUSION This Court has repeatedly said “there is no question that publishers [like PLN] . . . have a legitimate First Amendment interest in access to 20 prisoners.” Thornburgh, 490 U.S. at 408. With regard to PLN’s incarcerated reader, he also “retains those First Amendment rights that are not inconsistent with his status as a prisoner or with the legitimate penological objectives of the corrections system.” Pell, 417 U.S. at 822. FDOC’s regulations— and the Eleventh Circuit’s decision upholding them—deny publishers, their advertisers, and prison inmates their constitutionally protected right to free speech. Applying that regulation in an overbroad, arbitrary, and tenuous way, FDOC invokes vague penological objectives and threats to broadly suppress related and unrelated speech. We ask that this Court deny such an affront to the Constitution, grant PLN’s petition for certiorari, and reverse the Eleventh Circuit’s decision. RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED this day of October 15, 2018. Bruce E. H. Johnson Counsel of Record Caesar Kalinowski Davis Wright Tremaine LLP Attorneys for Amici Curiae 1201 Third Avenue, Suite 2200 Seattle, WA 98101 (206) 757-8069 brucejohnson@dwt.com caesarkalinowski@dwt.com 21