PLN US Supreme Court Amicus Brief in Goodman v. Georgia. Right of disabled prisoners to collect damages in ADA cases, 2005

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

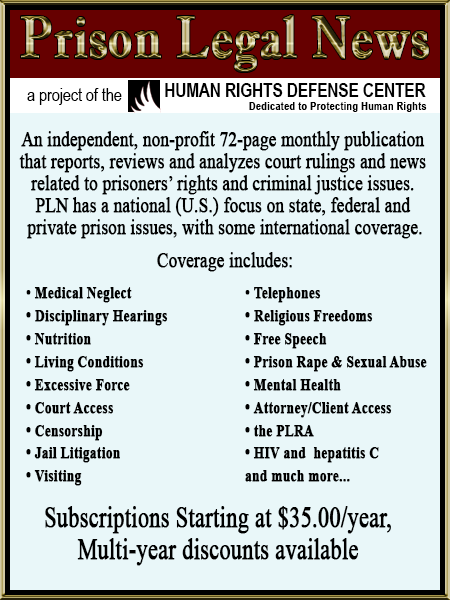

Nos. 04-1203 and 04-1236 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— UNITED STATES, Petitioner, v. STATE OF GEORGIA, et al., Respondents. ———— TONY GOODMAN, Petitioner, v. STATE OF GEORGIA, et al., Respondents. ———— On Writs of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit ———— BRIEF FOR ADAPT; AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PSYCHIATRY AND THE LAW; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF GEORGIA; AMERICAN COUNCIL OF THE BLIND; AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION; AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION; CENTER FOR HIV LAW AND POLICY; CITIZENS UNITED FOR REHABILITATION OF ERRANTS; HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH; LAMBDA LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.; THE LEGAL AID SOCIETY OF NEW YORK CITY; NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR RIGHTS PROTECTION AND ADVOCACY; NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF THE DEAF; NATIONAL HEALTH LAW PROGRAM; NATIONAL MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS SOCIETY; NATIONAL SPINAL CORD INJURY ASSOCIATION; PRISON LEGAL NEWS; SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS ———— July 29, 2005 PAUL M. SMITH * MARK R. HEILBRUN HEATHER M. TREW JENNER & BLOCK LLP 601 Thirteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 639-6000 * Counsel of Record Counsel for Amici [Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover] WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20001 STEPHEN F. GOLD 125 South Ninth Street Suite 700 Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 627-7225 Counsel for ADAPT ELIZABETH ALEXANDER DAVID C. FATHI 915 Fifteenth Street, NW 7th Floor Washington, DC 20005 (202) 457-0800 Counsel for American Civil Liberties Union BRIAN DIMMICK 1701 N. Beauregard Street Alexandra, VA 22311 (800) 342-2383 Counsel for American Diabetes Association JAMES ROSS 350 Fifth Avenue 34th Floor New York, NY 10118 (212) 290-4700 Counsel for Human Rights Watch JONATHAN GIVNER JENNIFER SINTON 120 Wall Street 15th Floor New York, NY 10005 (212) 809-8585 Counsel for Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. RICHARD TARANTO FARR & TARANTO Suite 800 1220 Nineteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 775-0184 Counsel for American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; Counsel for American Psychiatric Association GERALD WEBER 70 Fairlie Street, Suite 340 Atlanta, GA 30303 (404) 523-5398 Counsel for American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia CATHERINE HANSSENS 306 W. 38th Street, Suite 601 New York, NY 10018 (212) 564-4738 Counsel for Center for HIV Law and Policy STEVE BANKS JOHN BOSTON BETSY GINSBERG Pr i s one r s ’Ri g h t sPr o j e c t 199 Water Street New York, NY 10038 (212) 577-3300 Counsel for The Legal Aid Society of New York City KELBY BRICK 814 Thayer Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 587-1788 SUSAN STEFAN 246 Walnut Street Newton, MA 02460 Counsel for National Association of the Deaf Counsel for National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy JANE PERKINS SARAH SOMMERS 211 N. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 (919) 968-6308 LEONARD ZANDROW 6701 Democracy Boulevard Suite 300-9 Bethesda, MD 20817 (301) 214-4006 Counsel for National Health Law Program Counsel for National Spinal Cord Injury Association RHONDA BROWNSTEIN 400 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36104 (334) 956-8200 Counsel for Southern Poverty Law Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................................................. ii INTEREST OF AMICI...........................................................1 STATEMENT ........................................................................8 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT..............................................8 ARGUMENT .........................................................................9 I. THERE IS AN EXTENSIVE HISTORY OF UNCONSTITUTIONAL DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PRISONERS WITH DISABILITIES......9 A. Evidence in the Legislative History .....................9 B. Evidence in the Public Record ...........................11 1. Prisoners with Mobility Impairments...........12 2. Prisoners with Physical Illnesses..................14 3. Prisoners with Mental Illness .......................18 4. Prisoners with Vision and Hearing Impairments..................................................20 II. PROPHYLACTIC LEGISLATION IS AN APPROPRIATE RESPONSE TO PERSISTENT DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PRISONERS WITH DISABILITIES. ............................................22 CONCLUSION ....................................................................30 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CASES Armstrong v. Davis, 275 F.3d 849 (9th Cir. 2001)............ 21 Austin v. Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, 876 F. Supp. 1437 (E.D. Pa. 1995) ................................ 17 Beckford v. Irvin, 49 F. Supp. 2d 170 (W.D.N.Y. 1999) .............................................................................. 13 Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama Garrett, 531 U.S. 356 (2001) ........... 11, 20, 21, 24, 28, 29 Bonner v. Arizona Department of Corrections, 714 F. Supp. 420 (D. Ariz. 1989).......................................... 22 Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624 (1998)........................... 14 Carty v. Farrelly, 957 F. Supp. 727 (D.V.I. 1997) ........... 19 Casey v. Lewis, 834 F. Supp. 1477 (D. Ariz. 1993).... 17, 18 City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) ................. 23 Clarkson v. Coughlin, 898 F. Supp. 1019 (S.D.N.Y. 1995) .............................................................................. 21 Coleman v. Wilson, 912 F. Supp. 1282 (E.D. Cal. 1995) .............................................................................. 19 Crawford v. Indiana Dep’t of Corrections, 115 F.3d 481 (7th Cir. 1997)................................................. 23 Cummings v. Roberts, 628 F.2d 1065 (8th Cir. 1980) .............................................................................. 14 Doe v. Coughlin, 697 F. Supp. 1234 (N.D.N.Y. 1988) .............................................................................. 17 Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976).............................. 29 Freeman v. Berry, No. C 87-0259-L(A), 1994 WL 760820 (W.D. Ky. July 20, 1994).................................. 17 iii Howard v. City of Columbus, 521 S.E.2d 51 (Ga. Ct. App. 1999)................................................................ 15 Hunt v. Uphoff, 199 F.3d 1220 (10th Cir. 1999)............... 15 Inmates of Occoquan v. Barry, 717 F. Supp. 854 (D.D.C. 1989)................................................................. 19 Johnson v. Hardin County, 908 F.2d 1280 (6th Cir. 1990) .............................................................................. 13 Kiman v. New Hampshire Department of Corrections, 301 F.3d 13 (1st Cir. 2002), withdrawn on other grounds, 310 F.3d 785 (1st Cir. 2002) ....................................................................... 15 Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents, 528 U.S. 62 (2000) ....................................................................... 25, 27 Koehl v. Dalsheim, 85 F.3d 86 (2d Cir. 1996) .................. 22 LaFaut v. Smith, 834 F.2d 389 (4th Cir. 1987) ........... 12, 29 Leach v. Shelby County Sheriff, 891 F.2d 1241 (6th Cir. 1989) ....................................................................... 13 Leatherwood v. Campbell, No. CV-02-BE-2812-W (N.D. Ala. June 3, 2004), http://www.schr.org/ prisonsjails/press%20releases/Magistrate%20Rep ort%20Recommendation.pdf ........................................ 18 Love v. McBride, 896 F. Supp. 808 (N.D. Ind. 1995), aff’d sub nom. Love v. Westville Correctional Center, 103 F.3d 558 (7th Cir. 1996) .............................................................................. 13 Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146 (N.D. Cal. 1995) .............................................................................. 19 Miles v. Apex Marine Corp., 498 U.S. 19 (1990) ............. 28 Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721 (2003) ........................... 9, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30 iv Newman v. Alabama, 349 F. Supp. 278 (D. Ala. 1972), aff’d in relevant part, 503 F.2d 1320 (5th Cir. 1974) ................................................................. 12, 19 Nolley v. County of Erie, 776 F. Supp. 715 (W.D.N.Y. 1991)...................................................... 16, 17 Parrish v. Johnson, 800 F.2d 600 (6th Cir. 1986) ............ 13 Pennsylvania Department of Corrections v. Yeskey, 524 U.S. 206 (1998) ................................................. 10, 28 Plata v. Davis, 329 F.3d 1101 (9th Cir. 2003) .................. 18 Roop v. Squadrito, 70 F. Supp. 2d 868 (N.D. Ind. 1999) .............................................................................. 17 Ruiz v. Estelle, 503 F. Supp. 1265 (S.D. Tex. 1980), aff’d in relevant part, 679 F.2d 1115 (5th Cir. 1982) .................................................................. 14, 20, 24 School Board of Nassau County v. Arline, 480 U.S. 273 (1987) ................................................................ 14, 15 Simmons v. Cook, 154 F.3d 805 (8th Cir. 1998) ............... 12 South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) ................................................................. 25, 28, 30 Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509 (2004).................... passim Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. FCC, 520 U.S. 180 (1997) ................................................................ 23, 28 Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480 (1980) .................................. 19 Weeks v. Chaboudy, 984 F.2d 185 (6th Cir. 1993) ........... 12 Yarbaugh v. Roach, 736 F. Supp. 318 (D.D.C. 1990) .............................................................................. 13 STATUTES AND REGULATIONS 42 U.S.C. § 12101, et seq........................................... passim v 42 U.S.C. § 12101(a)(7) .................................................... 27 42 U.S.C. § 12101(a)(9) .................................................... 27 42 U.S.C. § 12141, et seq.................................................. 22 Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1997 et seq., Pub. L. No. 96-247, 94 Stat. 349 (1980).................................................... 9, 25, 26 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(Disability)(1)(ii) ................................ 14 29 C.F.R. § 1630.1(c)(1) ................................................... 14 Mich. Comp. Laws § 37.1301(b) ..................................... 27 LEGISLATIVE MATERIAL S. Rep. No. 101-116 (1989) ................ 10, 11, 16, 25, 26, 30 S. Rep. No. 95-1056 (1978) .......................................... 9, 25 H.R. Rep. No. 95-1058 (1978) ...................................... 9, 27 H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II) (1990), reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 303 ............................... 10, 11, 16, 26 Americans with Disabilities Act of 1989: Hearings on S.933 Before the Subcomm. on the Handicapped of the S. Comm. on Labor & Human Res., 101st Cong. (1989) ................................... 26 Civil Rights for Institutionalized Persons: Hearings on H.R. 2439 and H.R. 5791 Before the Subcomm. on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Admin. of Justice of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong. (1977) ......................................... 27 Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons: Hearings on S. 1393 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong. (1977) .......................................................... 27 vi Employment Discrim. Against Cancer Victims & the Handicapped: Hearing on H.R. 370 and H.R. 1294 Before the Subcomm. on Employment Opportunities of the H. Comm. on Educ. & Labor, 99th Cong. (1985) .............................................. 26 136 Cong. Rec. S9680 (daily ed. July 13, 1990)............... 16 MISCELLANEOUS Cal. Att’y Gen., Comm’n on Disability, Final Report (Dec. 1989)......................................................... 11 Anne-Marie Cusac, “The Judge Gave Me Ten Years. He Didn’t Sentence Me to Death”: Inmates with HIV deprived of proper care, The Progressive, July 2000 ................................................... 18 Lawrence O. Gostin et al., AIDS Litigation Project: A National Survey of Federal, State, & Local Cases Before Courts and Human Rights Commissions (1990)....................................................... 18 Theodore M. Hammett et al., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 1996-1997 Update: HIV/AIDS, STD’s, and TB in Correctional Facilities (July 1999)................................ 18 Reynolds Holding, State Prisons Settle Disability Bias Lawsuit, S.F. Chron., Aug. 12, 1998...................... 20 Human Rights Watch, Ill-Equipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness (2003).................19-20 Michael Mushlin, Rights of Prisoners (2d ed. 1993 & Supp. 2001) ................................................................ 29 U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Accommodating the Spectrum of Individual Abilities (1983) ......................... 10 Paul von Zielbauer, As Health Care in Jails Goes Private, 10 Days Can Be a Death Sentence, N.Y. Times, Feb. 27, 2005...................................................... 15 INTEREST OF AMICI1 Amici are nineteen professional organizations, civil liberties groups, prison-rights projects, and organizations that focus on improving the lives of individuals with disabilities, all of which recognize the essential role that Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”) plays in ameliorating the long history of state discrimination against prisoners with disabilities. ADAPT is a national organization composed primarily of persons with severe physical disabilities, including persons with spina bifida, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, quadriplegia, paraplegia, head and brain injuries, poliomyelitis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, sensory disabilities, and cognitive, mental and developmental disabilities. ADAPT has a long history and record of enforcing the civil rights of people with disabilities. ADAPT participated in the political and legislative process to pass the 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq. The American Academy of Psychiatry and The Law was founded in 1969 and has approximately 2000 members. It is devoted to issues at the intersection of psychiatry and the law and has participated as amicus in several cases in this Court. The American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) is a nationwide, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization with more than 400,000 members, dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality embodied in the Constitution and this nation’s 1 The parties have consented to the submission of this brief. Their letters of consent have been lodged with the Clerk of this Court. None of the parties authored this brief in whole or in part, and no one other than amici or their counsel contributed money or services to the preparation or submission of this brief. 2 civil rights laws. Consistent with that mission, the National Prison Project of the ACLU Foundation was established in 1972 to protect and promote the civil and constitutional rights of prisoners. The American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia is one of the ACLU’s state affiliates. The American Council of the Blind (“ACB”) is a national nonprofit, consumer organization of the blind, with seventy affiliates and members in all fifty states. Its mission is to improve the quality of life, equality of opportunity, and independence for all persons who are blind. To that end, ACB seeks to educate policy makers about the needs and capabilities of people who are blind, and to assist individuals and organizations wishing to advocate for programs and policies that meet the needs of people who are blind, or visually impaired. ACB members were very involved in the efforts that led to the passage of the ADA. Therefore, we are very disturbed about the legal challenges to its constitutionality which have been raised in recent years. We are especially concerned that state governments are increasingly taking up the cause of those who would weaken the ADA’s effectiveness. We urge this Court to give careful consideration to the implications of such challenges for the rights and welfare of people with disabilities who live and work within those states. The American Diabetes Association (“ADA”) is the nation’s leading nonprofit health organization providing diabetes research, information and advocacy. The mission of the organization is to prevent and cure diabetes, and to improve the lives of all people affected by diabetes. As part of its mission, ADA advocates for the rights of people with diabetes and supports strong public policies and laws to protect persons with diabetes against discrimination. ADA 3 has approximately 435,000 general members and nearly 18,000 health care professional members. The American Psychiatric Association, with approximately 40,000 members, is the Nation’s largest organization of physicians specializing in psychiatry. It has participated in numerous cases in this Court, including Olmstead v. L.C. ex rel. Zimring, 527 U.S. 581 (1999). Its members have a strong interest in the constitutionality of the ADA as it bars government entities’ discrimination against persons with disabilities, including persons with mental illnesses or disabilities. The Center for HIV Law and Policy, an independent project of the National Center for Civic Innovation, is the country’s first legal and policy resource bank and strategy center for advocates addressing HIV discrimination and the legal needs of those living with HIV. The central mission of the Center is to advance the just treatment of people affected by HIV by working to coordinate, improve and expand HIV advocacy and law reform efforts on their behalf, and to make this advocacy more responsive to their unaddressed needs. The availability of the ADA’s remedies to state-sponsored disability-based discrimination is particularly important to people with HIV, who continue to suffer irrational, disparate treatment often inspired by fear of their disease, particularly in state correctional facilities that chronically have denied them essential services, access to basic programs afforded other inmates, and life-saving medical treatment. Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants (“CURE”) is a national prison reform organization with approximately 15,000 members, mostly comprised of prisoners and their families. Many of these prisoners have physical and mental disabilities. CURE’s primary goals are (1) to limit the use prison to only those for whom it is absolutely necessary; and 4 (2) to advocate for the provision of rehabilitative opportunities to help prisoners improve their lives. Human Rights Watch is a non-profit organization established in 1978 that investigates and reports on violations of fundamental human rights in over 70 countries worldwide, with the goal of securing the respect of these rights for all persons. It is the largest international human rights organization based in the United States. By exposing and calling attention to human rights abuses committed by state and non-state actors, Human Rights Watch seeks to bring international public opinion to bear upon offending governments and others and thus bring pressure on them to end abusive practices. In the United States, Human Rights Watch has addressed a range of human rights issues, including U.S. prison conditions. Human Rights Watch has filed amicus briefs before various bodies, including U.S. courts and international tribunals. The treatment of men and women incarcerated in U.S. jails and prisons has been a longstanding priority of Human Rights Watch, and is the subject of numerous Human Rights Watch reports. Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. (“Lambda Legal”) is a national non-profit organization committed to achieving full recognition of the civil rights of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, transgender people and those with HIV through impact litigation, education and public policy work. Founded in 1973, Lambda Legal is the oldest and largest legal organization addressing these concerns. Since 1983, when it filed the nation’s first AIDS discrimination case, Lambda Legal has appeared as counsel or amicus curiae in scores of cases in state and federal courts on behalf of people living with HIV or other disabilities. 5 The Legal Aid Society of New York City is a private organization that has provided free legal assistance to indigent persons in New York City for more than 125 years. Through its Prisoners’ Rights Project, the Society seeks to ensure that prisoners are afforded full protection of their constitutional and statutory rights. The Society advocates on behalf of prisoners in New York City jails and New York state prisons, and where necessary conducts class action litigation on prison conditions, including litigation on behalf of prisoners with physical and mental disabilities. The National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy (“NARPA”) includes recipients of mental health and developmental disabilities services; lay, professional, and self-advocates; family members; service providers; disability rights attorneys; and teachers at schools of law, social work, and public policy. It is dedicated to promoting the preferred options of people who have been labeled mentally disabled. Established in 1880, the National Association of the Deaf (“NAD”) is the nation’s oldest and largest consumer-based, nonprofit organization promoting, protecting, and preserving the civil rights and quality of life of 28 million deaf and hard of hearing Americans. As a national federation of state association, organizational and corporate affiliates, the advocacy work of the NAD encompasses a broad spectrum of areas including, but not limited to, accessibility, education, employment, health care, mental health, rehabilitation, technology, telecommunications, and transportation. The NAD is committed to ensuring that deaf and hard of hearing individuals in the United States have equal access to the facilities and services of, and an equal opportunity to participate in all programs and activities of state and local governments, including prisons and correctional facilities. Removal of communication barriers by providing reasonable 6 accommodations, including auxiliary aids and services, is necessary to ensure access by individuals with sensory disabilities. The NAD is a private, nonprofit, non-stock, membership organization incorporated in the District of Columbia. The NAD has no parent corporation. For more than thirty-five years, the National Health Law Program (“NHeLP”) has engaged in legal and policy analysis on behalf of low income and working poor people, people with disabilities, the elderly, and children. NHeLP has provided legal representation and conducted research and policy analysis on issues affecting the health status and health access of these groups. As such, NHeLP has worked with the ADA, and the program’s work and our clients will be significantly affected by the Court’s decision in this case. The National Multiple Sclerosis Society is dedicated to ending the devastating effects of multiple sclerosis. The Society supports more MS research and serves more people with MS than any national voluntary MS organization in the world. Through its 50-state network of chapters, the Society funds research, furthers education, advocates for people with disabilities, and provides a variety of empowering programs for approximately 400,000 Americans who have MS and their families. The Society believes that every individual has the fundamental right to lead a full, productive life via the support of laws that promote equality of opportunity for all citizens. The ADA has proven to be a major advancement in the public awareness of disability rights and has prompted substantial improvements in local disability regulations. The Society’s participation here reflects its commitment to the right of every American to be free from discrimination and lack of independence under law. The National Spinal Cord Injury Association is the nation’s oldest and largest civilian organization dedicated to 7 helping the hundreds of thousands of Americans coping with the results of spinal cord injury and disease. Our mission is to enable people with spinal cord injuries and diseases to achieve their highest level of independence, health, and personal fulfillment by providing resources, services, and peer support. The ADA is a critical tool in helping individuals achieve those goals. Prison Legal News (“PLN”) is non-profit organization that advocates nationally on behalf of those imprisoned in American detention facilities. PLN publishes a magazine by the same name to educate its readers and the general public about the use of the civil justice system for the vindication of fundamental human and civil rights. Founded in 1971 and located in Montgomery, Alabama, the Southern Poverty Law Center has litigated numerous civil rights cases on behalf of minorities, women, people with disabilities, and other victims of discrimination. Many of the Center’s class actions have attacked unconscionable conditions of confinement in state prisons. Although the Center’s work is concentrated in the South, its attorneys appear in courts throughout the country to ensure that all people receive equal and just treatment under federal and state law. Many of amici have witnessed the extent of abuses against these prisoners as they have either litigated on their behalf or have worked to identify flaws in, and recommend solutions to, various penal systems’ mistreatment of prisoners with disabilities. Based on their intimate familiarity with unconstitutional discrimination against prisoners with disabilities and their review of pertinent legislative history and judicial decisions, amici maintain that Title II of the ADA was a congruent and proportional response to what is, and continues to be, a pattern and 8 practice of unconstitutional discrimination in the prison context. STATEMENT This case involves a paraplegic state prisoner who was denied minimally decent and equal treatment as a direct result of his disability. The details are set forth in Petitioner’s brief and need not be repeated here. It bears emphasis, however, that this kind of story is not an unusual one. To the contrary, persons with disabilities in state custody have been regularly discriminated against in ways that violate the Constitution. That reality was brought to Congress’s attention when it enacted the ADA. This extensive empirical record of unconstitutional discrimination establishes that Title II of the ADA is a congruent and proportional response to state discrimination against prisoners with disabilities. SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT The gross and indefensible mistreatment alleged by Petitioner is no isolated incident. As the extensive legislative history and public record reflect, state prisons routinely discriminate against inmates with disabilities in violation of their basic constitutional rights. Such prisoners depend on state officials to meet their basic needs but often find themselves discriminatorily denied essential protection and services. Congress, in determining the necessity of the ADA, was aware of the extensive record of state deprivations of the constitutional rights of incarcerated Americans with a broad range of physical and mental disabilities. To address this class of cases, among others, Congress expressly invoked the full sweep of its power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment when it enacted Title II of the ADA, which was presented to the President only after Congress integrated decades of 9 analysis and experience, including repeated ineffective attempts to remedy states’ systematic deprivation of rights guaranteed to the disabled by the Fourteenth Amendment and other constitutional provisions. Based on this pattern of unconstitutional discrimination against prisoners with disabilities, a faithful application of Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509 (2004), and Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721 (2003), leads to the conclusion that Title II — as applied to prisoners with disabilities — permissibly enforces, rather than substantively redefines, the rights protected by the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses, and the First and Eighth Amendments, as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, there exists a far more compelling historical predicate for abrogation of sovereign immunity vis-à-vis state discrimination against prisoners with disabilities than existed in Lane, or in Hibbs before it. Accompanied by the strong presumption of statutory validity, this historical record is dispositive in the case now before the Court. ARGUMENT I. THERE IS AN EXTENSIVE HISTORY OF UNCONSTITUTIONAL DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PRISONERS WITH DISABILITIES. A. Evidence in the Legislative History The legislative history of the ADA indicates that Congress was concerned with unconstitutional discrimination by states against prisoners with disabilities.2 The House and 2 As demonstrated by the legislative history of the earlier Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1997 et seq. (1980), Congress was well aware of the prevalence of state unconstitutional discrimination against prison inmates in general. See H.R. Rep. No. 95-1058, at 22 & n.54 (1978); S. Rep. No. 95-1056, at 16 (1978) (“[T]he basic 10 Senate Subcommittees “conclude[d] that there exists a compelling need to establish a clear and comprehensive Federal prohibition of discrimination on the basis of disability.” S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 5 (1989); H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 28 (1990), reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. 303, 310. The Subcommittees, in explaining the “need” for the ADA, relied on a U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report that identified discrimination in prisons as one of the “major social and legal mechanisms, practices, and settings in which handicap discrimination arises.” U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Accommodating the Spectrum of Individual Abilities, App. A at 165 (1983) (hereinafter “USCCR Rep.”); see also S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 6; H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 28, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 310 (citing USCCR Rep. at App. A at 168 (listing, inter alia, the “[i]nadequate treatment and rehabilitation programs in penal and juvenile facilities[,] [i]nadequate ability to deal with physically handicapped accused persons and convicts (e.g., accessible jail cells and toilet facilities) [and] [a]buse of handicapped persons by other inmates”)). The ADA’s legislative history contains other references to discrimination against inmates with disabilities. S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 8; H.R. Rep. NO. 101-485(II), at 31, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 312 (“The [USCCR] recently concluded, with respect to people with disabilities, that: ‘Despite some improvements . . . [discrimination] persists in such critical areas as . . . institutionalization . . . .’” (quoting USCCR Rep. at 159; alteration in original)); see Pennsylvania Dep’t of Corr. v. Yeskey, 524 U.S. 206, 211-12 (1998) (holding that Congress’s reference to constitutional and Federal statutory rights of institutionalized persons are being violated on such a systematic and widespread basis to warrant the attention of the Federal Government.” (quoting testimony of Drew S. Days, III, Assistant Att’y Gen. )). 11 institutionalization “can be thought to include penal institutions”). In hearings leading to the enactment of the ADA, Congress received extensive testimony regarding disability discrimination against inmates in state prisons. See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 6; H.R. Rep. No. 101485(II), at 28, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 310 (citing USCCR Rep., App. A at 168); Cal. Att’y Gen., Comm’n on Disability, Final Report 103 (Dec. 1989) (“[A] parole agent sent a man who uses a wheelchair back to prison since he did not show up for his appointments even though he explained that he could not make the appointments because he was unable to get accessible transportation.”). Moreover, a congressionally designated Task Force submitted to Congress several thousand documents evidencing discrimination and segregation in the provision of public services, including in the treatment of persons with disabilities in prisons and jails. See Board of Tr. of the Univ. of Ala. v. Garrett, 531 U.S. 356, 391-424 (2001) (App. C to Justice Breyer’s dissent); id. at 393 (“jail failed to provide person with disability medical treatment” (quoting Alaska at 55)); id. at 405 (“deaf people arrested and held in jail overnight without explanation because of failure to provide interpretive services” (quoting Illinois at 572)); id. at 409 (“public libraries, state prison, and other state offices lacked” telecommunications for the deaf (quoting Maryland at 787)); id. at 414 (“prisoners with developmental disabilities subjected to longer terms and abused by other prisoners in state correctional system” (quoting New Mexico at 1091)); id. at 415 (“police arrested and jailed deaf person without providing interpretive services” (quoting North Carolina at 1161)). B. Evidence in the Public Record In addition to the explicit legislative record of unconstitutional discrimination by states against prisoners 12 with disabilities, there is overwhelming evidence in the public record of a history of state violations of the constitutional rights of inmates in four specific contexts: Mobility Impairments, Physical Illnesses, Mental Illness, and Vision and Hearing Impairments. 1. Prisoners with Mobility Impairments Eighth Amendment jurisprudence is replete with examples of states violating the basic constitutional rights of prisoners with mobility impairments. Indeed, prison officials frequently fail to attend to the basic life needs of prisoners with mobility impairments. See, e.g., LaFaut v. Smith, 834 F.2d 389, 393-94 (4th Cir. 1987) (finding “deliberate indifference” on the part of prison officials in failing to provide rehabilitation therapy and toilet facilities to a paralyzed inmate who was required to drag his body across the floor to use the commode, which was not adequate to support him). As one court put it, the frequent denial of basic elements of adequate medical treatment for prisoners with mobility impairments “illustrate[s] the pervasive and gross neglect of prisoners’ medical needs” in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Newman v. Alabama, 349 F. Supp. 278, 284 (D. Ala. 1972), aff’d in relevant part, 503 F.2d 1320 (5th Cir. 1974); see id. at 285 (finding systemic constitutional violations of prisoners’ rights in the Alabama prison system including the death of a quadriplegic inmate, who spent many months in the hospital confined to a bed, leading to bedsores, which developed maggots from lack of care “until the stench pervaded the entire ward”). Other examples are legion. See, e.g., Simmons v. Cook, 154 F.3d 805, 808 (8th Cir. 1998) (concluding that prison officials were deliberately indifferent to needs of paraplegic prisoner, whose food tray slot was wheelchair-inaccessible, and who could not use toilet); Weeks v. Chaboudy, 984 F.2d 185, 187 (6th Cir. 1993) (finding violation of Eighth 13 Amendment where paralyzed inmate was not permitted a wheelchair in his cell, not permitted to shower, and denied admission to the prison infirmary); Leach v. Shelby County Sheriff, 891 F.2d 1241, 1243 (6th Cir. 1989) (finding a policy or custom of deliberate indifference to serious medical needs of paraplegic inmates; evidence showed that, “[d]espite his medical need for cleanliness, [an inmate] was not bathed for several days,” “was forced to remain for long periods of time in his own urine due to inadequate catheter supplies and was given inadequate aid for his bowel training needs despite his repeated requests for help”); Parrish v. Johnson, 800 F.2d 600, 603, 605 (6th Cir. 1986) (prison guard repeatedly assaulted paraplegic inmates with knife, forced them to sit in own feces, and taunted them with remarks like “crippled bastard” and “[you] should be dead”); Beckford v. Irvin, 49 F. Supp. 2d 170, 180 (W.D.N.Y. 1999) (finding Eighth Amendment violation where plaintiff was regularly deprived of his wheelchair for extended periods of time, unable to shower, and could not use a cup to attempt to bathe by taking water from his cell toilet or drinking fountain); Yarbaugh v. Roach, 736 F. Supp. 318, 320 (D.D.C. 1990) (finding violation of Eighth Amendment where prisoner debilitated by multiple sclerosis failed to receive adequate medical care for nearly a year). Inmates with disabilities have also been denied accommodations such as wheelchairs or crutches, without which they are unable to perambulate and participate in prison programs, thus depriving the prisoners of fundamental constitutional liberties. See, e.g., Love v. McBride, 896 F. Supp. 808, 809-10 (N.D. Ind. 1995), aff’d sub nom. Love v. Westville Corr. Ctr., 103 F.3d 558, 559 (7th Cir. 1996) (quadriplegic denied use of prison’s facilities, unable to participate in substance abuse education, church or transition programs available to inmate population); Johnson v. Hardin County, 908 F.2d 1280, 1283-84 (6th Cir. 1990) (holding 14 jailers’ refusal to provide crutches to inmate violated Eighth Amendment); Cummings v. Roberts, 628 F.2d 1065, 1068 (8th Cir. 1980) (holding jailer’s denial of a wheelchair to a prisoner supports claim for cruel and unusual punishment); Ruiz v. Estelle, 503 F. Supp. 1265, 1340-44 (S.D. Tex. 1980) (finding inmates with mobility impairments denied access to virtually all programs and activities available to general population and concluding that the “total picture of physically handicapped inmates in TDC is one marked by the extreme indifference and inflexibility of prison officials”), aff’d in relevant part, 679 F.2d 1115 (5th Cir. 1982); see also id. at 1346 (opining that “only minor accommodations” would have avoided these constitutional difficulties, but that the state’s “failure to make those minor adjustments needlessly subjects physically-handicapped prisoners to cruel and unusual punishment”). The number, magnitude and similarity of these cases — indicting the “care” prison officials provide — underscores the seriousness and pervasiveness of the ill-treatment of prisoners with mobility impairments. 2. Prisoners with Physical Illnesses Diseases, both communicable and non-communicable, are considered disabilities under federal law. School Bd. of Nassau County v. Arline, 480 U.S. 273, 284-86 (1987) (finding that teacher with susceptibility to tuberculosis qualified for protection under § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973);3 see 28 C.F.R. § 35.104(Disability)(1)(ii) (defining “physical or mental impairment” under ADA to include “contagious and noncontagious diseases and conditions”). 3 The ADA is interpreted consistent with and guided by the Rehabilitation Act. See Bragdon v. Abbott, 524 U.S. 624, 631-32 (1998) (concluding that 42 U.S.C. § 12201(a) “requires us to construe the ADA to grant at least as much protection as provided by the regulations implementing the Rehabilitation Act”); 29 C.F.R. § 1630.1(c)(1). 15 This Court previously recognized that Congress’s passage of laws prohibiting discrimination against individuals with disabilities reflected an understanding of the extensive history of discrimination against those with contagious illnesses. Arline, 480 U.S. at 284-85 (“The [Rehabilitation] Act is carefully structured to replace such reflexive reactions to actual or perceived handicaps with actions based on reasoned and medically sound judgments[.]”); see also id. at 284-86 & nn.11-15 (discussing Congress’s concern with irrational discrimination against those with diseases). The case law makes clear that Congress had ample basis for concluding that state prisons were discriminating against prisoners with various illnesses.4 For example, prisoners who suffer from non-communicable, chronic conditions often suffer significant harm and disparate levels of restrictiveness as a consequence of denial of care and accommodations required by their disability. In one case, a state prisoner with Lou Gehrig’s disease alleged that he was denied a cane needed for walking, a chair needed for showers, and a suitable toilet, as well as being improperly handcuffed. Kiman v. N.H. Dep’t of Corr., 301 F.3d 13, 15-16 (1st Cir. 2002), withdrawn on other grounds, 310 F.3d 785 (1st Cir. 2002); see also Hunt v. Uphoff, 199 F.3d 1220 (10th Cir. 1999) (finding violation of Eighth Amendment where inmate with diabetes was denied insulin, resulting in a heart attack and subsequent bypass surgery, resulting in his death from acute blockage of coronary artery graft); cf. Howard v. City of Columbus, 521 S.E.2d 51 (Ga. Ct. App. 1999) (finding 4 Accounts of discrimination against prisoners with physical illnesses have also been reported extensively in the news media. See, e.g., Paul von Zielbauer, As Health Care in Jails Goes Private, 10 Days Can Be A Death Sentence, N.Y. Times, Feb. 27, 2005, at 1 (describing denial of basic health care and treatment protocols to inmates with physical illnesses, resulting in deaths of inmate with Parkinson’s disease and inmate suffering from heart attack). 16 case appropriate for trial where inmate died of diabetesrelated complications after officials failed to identify his diabetes, failed to provide any treatment or special diet to control his diabetes, and failed to adequately treat him when his high blood glucose levels caused him to become visibly ill). Communicable diseases present another major challenge. The failure of prison officials to acknowledge and respond to inmates’ serious medical conditions can result in forms of discrimination that not only violate the Eighth Amendment but implicate the ADA. For example, prison officials have engaged in a pattern of discrimination against prisoners who have HIV.5 In one typical case, a former prisoner brought suit challenging the prison’s public identification of her HIVpositive status, its automatic segregation of HIV-positive inmates, and the denial of access to the law library and religious services based on HIV-positive status. Nolley v. County of Erie, 776 F. Supp. 715, 717-18 (W.D.N.Y. 1991). The court concluded that the prison’s policy of identifying all HIV-positive prisoners by placing red stickers on their 5 Congress, in enacting the ADA, focused on HIV as an area of disability discrimination in need of a federal remedy. See S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 8; H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 31, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 313 (“[T]he Commission concluded that discrimination against individuals with HIV infection is widespread and has serious repercussions for both the individual who experiences it and for this nation’s efforts to control the epidemic.”) (Hearing Before the H. Subcomm. on Select Educ. and S. Subcomm. on the Handicapped, 100th Cong. 40 (1988) (summarizing testimony of Adm. James Watkins, former chairperson of the President’s Comm’n on the H.I.V. Epidemic)); 136 Cong. Rec. S9680, 9681 (daily ed. July 13, 1990) (statement of Sen. Kennedy) (“The ADA marks an important and compassionate step in this Nation’s response to the HIV epidemic. The ADA will improve the quality of life for persons confronting AIDS.”). 17 “documents and personal items” was “not reasonably related to legitimate penological interests” and a violation of the constitutional right to privacy. Id. at 732-33. The court also found that the prison’s “policy of automatically segregating known HIV[-positive] inmates” without any review transgressed both the prisoner’s constitutional right to privacy, id. at 734-36, and her due process rights. Id. at 738. Finally, the court held that the prison’s denial of access to the law library violated the HIV-positive prisoner’s right of access to the courts, id. at 741, and its denial of access to religious services abridged the inmate’s First Amendment rights. Id. at 741-42. Other courts have found similar constitutional violations by states against HIV-positive prisoners. See, e.g., Casey v. Lewis, 834 F. Supp. 1477, 1488-91 & nn.109 & 123 (D. Ariz. 1993) (finding constitutional violations by prison system, in part, because of the treatment of HIV-positive prisoners); Freeman v. Berry, Civ. A No. C. 87-0259-L(A), 1994 WL 760820, at *2-*3 (W.D. Ky. July 20, 1994) (denying motion to alter judgment against state correctional official who was found to be deliberately indifferent, in violation of HIVpositive prisoner’s constitutional rights, for refusing to transfer prisoner to ensure his safety); cf. Roop v. Squadrito, 70 F. Supp. 2d 868, 876-77 (N.D. Ind. 1999) (finding genuine issue of material fact existed regarding HIV-positive prisoner’s claim for unconstitutional conditions of confinement); Doe v. Coughlin, 697 F. Supp. 1234, 1243 (N.D.N.Y. 1988) (preliminarily enjoining prison from involuntarily transferring HIV-positive prisoners). In addition to adverse judgments, states have settled — or entered into consent decrees regarding — numerous suits by HIV-positive prisoners alleging constitutional violations. See, e.g., Austin v. Pa. Dep’t of Corr., 876 F. Supp. 1437, 1453-54 (E.D. Pa. 1995) (approving class action settlement 18 between inmates and state prison system, which, inter alia, eliminated “unlawful discrimination against HIV-infected individuals” regarding work assignments and privacy of medical information); see also Plata v. Davis, 329 F.3d 1101, 1103 (9th Cir. 2003) (discussing the underlying settlement of original claims by female prisoners, including a sub-class of HIV-positive prisoners, who alleged violations of their constitutional rights); Leatherwood v. Campbell, No. CV-02BE-2812-W (N.D. Ala. June 2, 2004), http://www.schr.org/prisonsjails/press%20releases/Magistrat e%20Report%20Recommendation.pdf (approving settlement of class action brought by HIV-positive inmates against state correctional facility alleging violations of constitutional rights). See generally Anne-Marie Cusac, “The Judge Gave Me Ten Years. He Didn’t Sentence Me to Death”: Inmates With HIV Deprived of Proper Care, The Progressive, July 2000, at 22 (citing numerous cases brought by HIV-positive prisoners and relief granted by courts); Lawrence O. Gostin et al., AIDS Litigation Project: A National Survey of Federal, State, & Local Cases Before Courts and Human Rights Commissions 135-54 (1990) (listing cases); Theodore M. Hammett, et al., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 1996-1997 Update: HIV/AIDS, STD’s, and TB in Correctional Facilities at 93-97 (July 1999) (listing cases). In sum, as these examples illustrate, Congress had an ample basis for concluding that prisoners with disabilities caused by various diseases had been subjected to harmful and discriminatory treatment. 3. Prisoners with Mental Illness Prisons have frequently failed to accommodate the needs of prisoners with mental illness and frequently deny them basic and essential medical care, often leading to their exclusion from opportunities available to other prisoners. See, e.g., Casey, 834 F. Supp. at 1550 (“The Court finds the 19 treatment of seriously mentally ill inmates to be appalling . . . . The Court considers this treatment of any human being to be inexcusable and cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the eighth amendment of the Constitution;” “[r]ather than providing treatment . . . [the prison] punishes these inmates by locking them down in small, bare segregation cells for their actions that are the result of their mental illnesses.”). Viewing only a small sample of the multitude of relevant cases is sufficient to reveal the extent of state discrimination against mentally ill prisoners. See, e.g., Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480, 492-96 (1980) (affirming district court’s conclusion that the state’s policy of involuntarily transferring prisoners to mental health facilities implicated a liberty interest under the due process clause); Carty v. Farrelly, 957 F. Supp. 727, 738 (D.V.I. 1997) (“[I]nmates who demonstrate unusual behavior indicative of mental illness are not hospitalized for diagnosis; rather, they are sometimes separated into separate cell clusters or locked down into solitary confinement.”); Madrid v. Gomez, 889 F. Supp. 1146, 1255-59 (N.D. Cal. 1995) (prisoner with mental illness who smeared feces was placed in scalding water until his skin peeled off and hung in large clumps around his legs); Coleman v. Wilson, 912 F. Supp. 1282 (E.D. Cal. 1995) (remedying excessive use of physical restraints with prisoners with mental illness); Inmates of Occoquan v. Barry, 717 F. Supp. 854, 863-64, 867 (D.D.C. 1989) (mentally ill inmates housed in cell block used for administrative and punitive segregation, where they were “locked in their cells for 23 hours a day with no social contact and . . . receive[d] no treatment except for medication”); Newman v. Alabama, 349 F. Supp. at 284 (prisoners with mental illness who acted violently were “removed to lockup cells . . . not equipped with restraints or padding . . . where they [were left] unattended”); see generally Human Rights Watch, IllEquipped: U.S. Prisons and Offenders with Mental Illness 20 34-37, 46-48 (2003) (collecting cases describing unique and systemic abuse of prisoners with mental illness by prisons). The problem also extends to the population of prisoners with mental retardation and other developmental disabilities. For example, California “admitted violating the [ADA] and the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, and agreed to create special programs for the estimated 5,000 prisoners with mental retardation, autism, cerebral palsy and other developmental disabilities.” Reynolds Holding, State Prisons Settle Disability Bias Lawsuit, S.F. Chron., Aug. 12, 1998, at A20; see also id. (noting numerous instances of abuse of inmates with developmental disabilities by guards and other prisoners). Similarly, in Ruiz v. Estelle, 503 F. Supp. 1265 (S.D. Tex. 1980), the court found the Texas Department of Corrections (“TDC”) “failed to meet its constitutional obligation to provide minimally adequate conditions of incarceration for mentally retarded inmates.” Ruiz, 503 F. Supp. at 1346. Of significance to the court was the fact that TDC refused to provide counsel or counsel substitute to assist mentally retarded inmates during disciplinary hearings. Id. at 1344. These prisoners with mental disabilities had an “inherent inclination to plead guilty” and they “serve[d] longer sentences than [other] inmates.” Id. The TDC’s systematic denial of counsel was found to violate the due process clause. Id. at 1346 (citing Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 570 (1974)). 4. Prisoners with Impairments Vision and Hearing States frequently violate the constitutional rights of prisoners with vision and hearing disabilities and Congress was undoubtedly aware of the plight of these inmates. See Garrett, 531 U.S. at 405 (Appendix C to Justice Breyer’s dissent) (“deaf people arrested and held in jail overnight 21 without explanation because of failure to provide interpretive services” (quoting Illinois at 572)); id. at 409 (“public libraries, state prisons, and other state offices lacked [telecommunications for the deaf]” (quoting Maryland at 787)); id. at 415 (“police arrested and jailed deaf person without providing interpretive services” (quoting North Carolina at 1161)). In Clarkson v. Coughlin, 898 F. Supp. 1019 (S.D.N.Y. 1995), a class of deaf and hearing-impaired inmates brought suit against the state prison system. The court found that the prison’s refusal to provide reasonable accommodations violated the Constitution. Id. at 1032-34. The court granted summary judgment to the class and held the prison in violation of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because of the prison’s failure to provide interpreters for disciplinary proceedings, educational programs and essential communications with physicians. Id. at 1032-34, 1041-44, 1048-51. The court also found that the prison was deliberately indifferent, and, thus, in violation of the Eighth Amendment, in light of the prison’s “systematic” refusal to enable hearing-impaired inmates to communicate with medical personnel. Id. at 1032-34, 1042-43; see also id. at 1049 (concluding the prison’s “systematic pattern of inadequacy of treatment . . . caus[ed] class members unwarranted suffering”). Finally, the court held that the prison transgressed the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by excluding hearing-impaired female inmates from the few available assistive services. Id. at 1043-44, 1051. Numerous other courts have found that state prisons discriminated against inmates with hearing and vision disabilities in violation of the United States Constitution. See, e.g., Armstrong v. Davis, 275 F.3d 849, 858 (9th Cir. 2001) (affirming district court’s system-wide injunction 22 against California prison system based on the district court’s holding that the state’s parole and parole revocation hearings were “not in substantial compliance with the ADA or the Rehabilitation Act, and that it routinely denied plaintiffs their rights under the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution”); Koehl v. Dalsheim, 85 F.3d 86, 88-89 (2d Cir. 1996) (reversing district court and holding that inmate properly stated a claim for violation of the Eighth Amendment when prison deprived inmate of medicallyprescribed glasses); Bonner v. Ariz. Dep’t of Corr., 714 F. Supp. 420, 426 (D. Ariz. 1989) (holding that inmate “has a due process liberty interest in the presence of a qualified sign language interpreter at all stages in the prison’s disciplinary procedure”). II. PROPHYLACTIC LEGISLATION IS AN APPROPRIATE RESPONSE TO PERSISTENT DISCRIMINATION AGAINST PRISONERS WITH DISABILITIES. In Tennessee v. Lane, 541 U.S. 509 (2004), this Court explained that Title II of the ADA, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101, 12141, et seq., responds to a history of unequal treatment in, inter alia, the “administration of . . . the penal system.” 541 U.S. at 525. Yet the Eleventh Circuit has misapplied this Court’s Eleventh Amendment jurisprudence and declared Title II of the ADA unconstitutional and unenforceable in the prison administration context. The lower court’s ruling is incompatible with the historical record of state discrimination against prisoners with disabilities compiled by Congress before enactment of the ADA.6 The disregard of this 6 See Lane, 541 U.S. at 516 (“The ADA was passed by large majorities in both Houses of Congress after decades of deliberation and investigation into the need for comprehensive legislation to address discrimination against persons with disabilities. In the years immediately preceding the ADA’s enactment, Congress held 13 hearings and created a special task 23 historical record is an affront to Congress’s power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment and protect against pervasive and enduring state constitutional violations.7 Consistent with the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment, “Congress may enact so-called prophylactic legislation that proscribes facially constitutional conduct, in order to prevent and deter unconstitutional conduct.” Nevada Dep’t of Human Res. v. Hibbs, 538 U.S. 721, 727-28 (2003); see also City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 518 (1997). force that gathered evidence from every State in the Union. The conclusions Congress drew from this evidence are set forth in the task force and Committee Reports, described in lengthy legislative hearings, and summarized in the preamble to the statute.”); see generally Crawford v. Ind. Dep’t of Corr., 115 F.3d 481, 486 (7th Cir. 1997) (Posner, C.J.) (“The Americans with Disabilities Act was cast in terms not of subsidizing an interest group but of eliminating a form of discrimination that Congress considered unfair and even odious. The Act assimilates the disabled to groups that by reason of sex, age, race, religion, nationality, or ethnic origin are believed to be victims of discrimination. Rights against discrimination are among the few rights that prisoners do not park at the prison gates.”) (citations omitted; emphasis added). 7 Congress’s enforcement power, as this Court has often acknowledged, is a “broad power indeed.” Lane, 541 U.S. at 518 (citing Mississippi Univ. for Women v. Hogan, 458 U.S. 718, 732 (1982)); see also id. at 518 n.3 (“‘Whatever legislation is appropriate, that is, adapted to carry out the objects the amendments have in view, whatever tends to enforce submission to the prohibitions they contain, and to secure to all persons the enjoyment of perfect equality of civil rights and the equal protection of the laws against state denial or invasion, if not prohibited, is brought within the domain of congressional power.’”) (quoting Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345-46 (1880)); City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 517-18 (1997). This Court’s precedent “‘accord[s] substantial deference to the predictive judgments of Congress,’” and the “sole obligation” of reviewing courts “is ‘to assure that, in formulating its judgments, Congress has drawn reasonable inferences based on substantial evidence.’” Turner Broad. Sys., Inc. v. FCC, 520 U.S. 180, 195 (1997) (“Turner II”) (quoting Turner Broad. Sys., Inc. v. FCC, 512 U.S. 622, 665-66 (1994) (“Turner I”)). 24 To uphold Section 5 legislation, this Court must: (1) “identify with some precision the scope of the constitutional right at issue[,]” Garrett, 531 U.S. at 365; (2) “examine whether Congress identified a history and pattern of unconstitutional” conduct by states regarding that constitutional right, id. at 368; and (3) evaluate whether Congress’s remedy is appropriate — that is, whether the remedy is congruent and proportional to the history and pattern of discrimination. Lane, 541 U.S. at 530. First, regarding the scope of the constitutional right at issue, Title II as applied to prisoners with disabilities clearly “seeks to enforce a variety of other basic constitutional guarantees.” Lane, 541 U.S. at 522-23. Indeed, state discrimination against prisoners with disabilities implicates a panoply of constitutional rights, including not just the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment’s ban on irrational disability discrimination, but also the Due Process Clause and the First and Eighth Amendments, as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. Second, there can be no doubt that Congress identified a pattern of discrimination against prisoners with disabilities. Moreover, for the reasons just explained and consistent with the access to judicial services rights implicated in Lane, 541 U.S. at 532-33, such discrimination is more likely to implicate constitutional rights in the prison context than in almost any other, because states have affirmative constitutional obligations toward those they hold in custody.8 8 See, e.g., Ruiz v. Estelle, 503 F. Supp. at 1344-46 (finding that the Texas Department of Corrections “failed to meet its constitutional obligation to provide minimally adequate conditions of incarceration for mentally retarded inmates,” in part, because the state refused to provide counsel or counsel substitute to assist mentally retarded inmates during disciplinary hearings). 25 Third, Title II is an appropriate remedial response to this history of discrimination in light of the extensive history of state infringement of the constitutional rights of prisoners In responding to this pattern of with disabilities.9 discrimination, Congress, as in Lane and South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966), confronted a “[d]ifficult and intractable problem,” where previous legislative attempts had failed,10 thus justifying added prophylactic measures in response. Kimel v. Fla. Bd. of Regents, 528 U.S. 62, 88 (2000); see also Lane, 541 U.S. at 531; Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 737 (upholding the FMLA as valid remedial legislation without regard to whether the failure to provide the statutorily mandated 12 weeks of leave violated the Fourteenth Amendment). That prophylactic remedy was designed to make it more practical for persons like vulnerable state prisoners to assert their rights. Not only does it authorize attorneys fees to prevailing parties, but it also eliminated the difficult burden of establishing the 9 In Lane, this Court broadly considered the full range of constitutional rights and Title II remedies at issue, framing its analysis in terms of the broad “class of cases implicating the accessibility of judicial services.” 541 U.S. at 531. The Court’s expansive review was appropriate because Congress necessarily responds not to the isolated claims of individual litigants, but to broad patterns of unconstitutional conduct by government officials. Accordingly, in this case it is appropriate to assess Title II’s constitutionality as applied to the entire class of cases implicating, in this Court’s words, “the administration of . . . the penal system.” Id. at 525, 530-31. 10 See S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 18 (section of report entitled “Current Federal and State Laws are Inadequate”); see also Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1997 et seq. Pub. L. No. 96247, 94 Stat. 349 (1980) (providing Attorney General the discretion to enforce the constitutional rights of inmates, but not creating a private right of action or imposing a reasonable accommodation requirement); S. Rep. No. 95-1056 at 17-18 (1978) (citing “unique inability of prisoners to assert their rights” and “inadequacy of legal services”). 26 requisite state of mind of the defendant — a burden that has often prevented successful assertion of valid constitutional claims. Just as past federal solutions were unavailing, Congress also found that state laws were “inadequate to address the pervasive problems of discrimination that people with disabilities are facing.” H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 47, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 329; see also S. Rep. No. 101-116, at 6 (1989) (“Discrimination still persists in such critical areas as . . . public services.”); S. Rep. No. 101-116 at 18 (section of report entitled “Current Federal and State Laws are Inadequate”); H.R. Rep. No. 101-485(II), at 48, reprinted in 1990 U.S.C.C.A.N. at 330 (50 State Governors’ Committees “report[ed] that existing State laws do not adequately counter . . . discrimination”). Among other things, Congress found that states — like their federal counterparts — failed to provide for private rights of action and compensatory damages, effectively leaving many victims of discrimination without available remedies.11 For example, in enacting the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1997, Congress cited “the possible conflicts of interest which State and other public officials appear to have 11 See Americans with Disabilities Act of 1989: Hearings on S. 933 Before the Subcomm. on the Handicapped of the Comm. on Labor & Human Res., 101st Cong. 386-94 (1989) (statement of the Nat’l Coal. for Cancer Survivorship); Employment Discrim. Against Cancer Victims & the Handicapped: Hearing on H.R. 370 & H.R. 1294 Before the Subcomm. on Employment Opportunities of the H. Comm. on Educ. & Labor, 99th Cong. 62 (1985) (statement of Rep. Moakley) (“[O]ne-fourth of the states have no protection for the handicapped. Additionally, even those states with laws differ greatly in their regulations.”) (ten-state survey showing gaps in coverage of laws). 27 in relation to institutionalized persons.” H.R. Rep. No. 951058, at 7-8 (1978).12 In addressing the enduring problem of disability discrimination, Congress concluded that states were in many respects responsible for the “history of purposeful unequal treatment” and participants in “the continuing existence of unfair and unnecessary discrimination and prejudice” against individuals with disabilities, 42 U.S.C. §§ 12101(a)(7) & (9), and those conclusions are “entitled to much deference.” Kimel, 528 U.S. at 81 (quotation marks omitted). As with state laws against gender discrimination that neither eliminated that continuing bias nor in any way weakened the rationale for subjecting states to federal prohibitions, see Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 729-37, Congress was likewise entirely justified in concluding that state laws against disability discrimination in state prisons had been wholly ineffective in combating the lingering effects of prior official discrimination and, of greater significance, in altering violative state behavior.13 12 See also Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons: Hearings on H.R. 2439 and H.R. 5791 Before the Subcomm. on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Admin. of Justice of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong. 29395 (1977) (statement of Drew S. Days, III, Assistant Att’y Gen.); Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons: Hearings on S. 1393 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 95th Cong. 31 (1977) (statement of Drew S. Days, III, Assistant Att’y Gen.) (providing examples from prisons of severe lack of adequate medical care resulting in critical injury and death, constitutionally inadequate conditions of confinement and acute physical abuse and criminal acts). 13 It is not insignificant that states also remain free to, and have, indiscriminately removed prisoners from the protection of their disability discrimination statutes. See, e.g., Mich. Comp. Laws § 37.1301(b). 28 In addition to the legislative history itself,14 the substantial class of judicial decisions involving state unconstitutional discrimination against inmates with disabilities evinces the need for Congress’s chosen remedy. See, e.g., Lane, 541 U.S. at 525 & n.11 (citing cases that “document a pattern of unequal treatment in the administration of . . . the penal system”); Garrett, 531 U.S. at 391-424 (App. C to Justice Breyer’s dissent) (citing excerpts from task force’s examples of discrimination); Yeskey, 524 U.S. at 211-12 (noting that the ADA’s findings about “discrimination ‘in such critical areas as . . . institutionalization,’ can be thought to include penal institutions”) (alteration in original; citation omitted). Importantly, the extensive historical record includes numerous claims, like Petitioner’s, asserting fundamental constitutional rights including: (i) the denial of access to religious services, law libraries, telephone and mail services, medical treatment, and rehabilitation, recreation, and work programs; (ii) the unconstitutional imposition (as in Petitioner’s case) of disparate terms of confinement and restraint solely because of the individuals’ disabilities; and (iii) the infliction of degrading, inhumane, and life14 The Court need not limit its review to the specific legislative record, although that record is replete with examples of unconstitutional state conduct in the areas encompassed by Title II and considered here. See Lane, 541 U.S. at 522-33 (relying on, inter alia, legislative history, statutes and judicial decisions); see also Turner II, 520 U.S. at 195 (examining evidence outside the legislative record to evaluate Congress’s exercise of legislative power); Miles v. Apex Marine Corp., 498 U.S. 19, 32 (1990) (courts should presume that Congress is aware of relevant legal precedents when it enacts remedial legislation). See generally Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 330 (“In identifying past evils,” for which Section 5 legislation is appropriate, “Congress obviously may avail itself of information from any probative source,” including the “information and expertise that Congress acquires in the consideration and enactment of earlier legislation”). 29 threatening conditions on prisoners with disabilities nationwide. Those claims arise under the First and Eighth Amendments, as applied to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses. It is notable that in the years between this Court’s decision in Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976), and Title II’s enactment, federal courts found numerous constitutional violations that overlap with Title II as it is applied to prisons.15 These representative cases — and those discussed in Part I, supra — exemplify just the sort of “confirming judicial documentation” absent from Title I. Garrett, 531 U.S. at 376 (Kennedy, J., concurring). 15 The Constitution forbids state prisons to act with deliberate indifference to the medical needs of prisoners. Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 104-06 (1976). This practice can subject prisoners with disabilities to multiple punishments: in addition to their sentence, they suffer unnecessary pain, loss of dignity, and, in some cases, a shortened lifespan. At the time Title II was enacted, however, state prisons nevertheless continued to abuse prisoners with disabilities, denying them these fundamental constitutional protections. See, e.g., LaFaut, 834 F.2d at 393-94 (deliberate indifference where paraplegic inmate was not provided convenient wheelchair-accessible toilet and was not provided adequate rehabilitation therapy during incarceration); Michael Mushlin, Rights of Prisoners § 3.15, at 167 n.199 (2d ed. 1993 & Supp. 2001) (collecting cases); see also supra Part I (discussing cases). While certainly not all constitutional claims by sick or injured inmates will be covered by Title II, it is nonetheless exceedingly difficult for inmates to satisfy the subjective element of the deliberate indifference standard — making prophylactic legislation inherently appropriate. See Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 736 (Congress justified in concluding that perceptions based on stereotype “lead to subtle discrimination that may be difficult to detect on a case-by-case basis”); see also Lane, 541 U.S. at 520 (“When Congress seeks to remedy or prevent unconstitutional discrimination, § 5 authorizes it to enact prophylactic legislation proscribing practices that are discriminatory in effect, if not in intent, to carry out the basic objectives of the Equal Protection Clause”). 30 In sum, the historical record in the instant case is significantly stronger than that justifying the appropriate application of Title II in Lane, and is far more robust than that in Hibbs. Accordingly, Title II of the ADA is a congruent and proportional response to state discrimination against inmates with disabilities. In fact, considering the vast historical evidence of these violations in the prison administration context, Title II accommodation seems at the very least reasonably tailored to provide the states with a practical method to avoid liability for constitutional violations in certain cases, notwithstanding the differences in proof underlying a Title II claim. As Hibbs makes clear, once Congress identifies a predicate of unconstitutional conduct that it seeks to remedy, Congress has flexibility in fashioning the remedy. See Hibbs, 538 U.S. at 734 n.10, 736-40. Congress’s Section 5 enforcement authority means nothing if it does not involve the power to ensure that constitutional violations are not left without a remedy. See, e.g., id. at 735-36; Katzenbach, 383 U.S. at 314-15. Congress properly chose a comprehensive remedial solution to this historical dilemma because to do otherwise would simply have placed disability rights in the same political vortex that for years proved utterly ineffective. See S. Rep. NO. 101-116 at 13 (like “throwing an 11-foot rope to a drowning man 20 feet offshore and then proclaiming you are going more than halfway.” (quoting Harold Russell, testifying for President’s Comm. on Employment of People with Disabilities)). The Court should not hesitate to uphold Congress’s power to protect the constitutional rights of persons with disabilities in the prison context. CONCLUSION The judgment below should be reversed. Respectfully submitted, PAUL M. SMITH Counsel of Record MARK R. HEILBRUN HEATHER M. TREW JENNER & BLOCK LLP 601 Thirteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 639-6000 Counsel for Amici STEPHEN F. GOLD 125 South Ninth Street Suite 700 Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 627-7225 RICHARD TARANTO FARR & TARANTO Suite 800 1220 Nineteenth Street, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 775-0184 Counsel for ADAPT Counsel for American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law; Counsel for American Psychiatric Association ELIZABETH ALEXANDER DAVID C. FATHI 915 Fifteenth Street, NW 7th Floor Washington, DC 20005 (202) 457-0800 Counsel for American Civil Liberties Union GERALD WEBER 70 Fairlie Street, Suite 340 Atlanta, GA 30303 (404) 523-5398 Counsel for American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia BRIAN DIMMICK 1701 N. Beauregard Street Alexandra, VA 22311 (800) 342-2383 Counsel for American Diabetes Association JAMES ROSS 350 Fifth Avenue 34th Floor New York, NY 10118 (212) 290-4700 Counsel for Human Rights Watch STEVE BANKS JOHN BOSTON BETSY GINSBERG Prisoners’ Rights Project 199 Water Street New York, NY 10038 (212) 577-3300 Counsel for The Legal Aid Society of New York City CATHERINE HANSSENS 306 W. 38th Street Suite 601 New York, NY 10018 (212) 564-4738 Counsel for Center for HIV Law and Policy JONATHAN GIVNER JENNIFER SINTON 120 Wall Street 15th Floor New York, NY 10005 (212) 809-8585 Counsel for Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. SUSAN STEFAN 246 Walnut Street Newton, MA 02460 Counsel for National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy KELBY BRICK 814 Thayer Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20910 (301) 587-1788 Counsel for National Association of the Deaf LEONARD ZANDROW 6701 Democracy Boulevard Suite 300-9 Bethesda, MD 20817 (301) 214-4006 Counsel for National Spinal Cord Injury Association July 29, 2005 JANE PERKINS SARAH SOMMERS 211 N. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 (919) 968-6308 Counsel for National Health Law Program RHONDA BROWNSTEIN 400 Washington Avenue Montgomery, AL 36104 (334) 956-8200 Counsel for Southern Poverty Law Center