ACLU Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform, 2020

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

••

•

.

'

••

.

:

ACLU RESEARCH REPORT

A Tale of Two Countries

Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

ACLU RESEARCH REPORT

A Tale of Two Countries

Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

© 2020 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

Acknowledgements

The report has been a project of the American Civil

Liberties Union (ACLU). The report was developed

by Ezekiel Edwards, Director, Criminal Law Reform

Project; content was led by Brooke Madubuonwu,

Director of Legal Analytics and Quantitative

Research; and the report was overseen and managed

by Emily Greytak, Director of Research. Data

collection, analysis, and visualization was conducted

by ACLU Analytics.

The primary authors are Ezekiel Edwards, Director,

Criminal Law Reform Project; Emily Greytak,

Director of Research; Brooke Madubuonwu, Director

of Legal Analytics and Quantitative Research;

Thania Sanchez, Senior Social Scientist; Sophie

Beiers, Data Journalist; Charlotte Resing, Policy

Analyst, National Political Advocacy Department;

Paige Fernandez, Policing Policy Advisor, National

Political Advocacy Department; and Sagiv Galai,

Paralegal, Criminal Law Reform Project.

The authors thank Rebecca McCray, Editor, for

her editorial assistance; Kadiesha Weise, Legal

Administrative Assistant, for her assistance

reviewing research; Alex Yurcaba, Data Analyst, for

his assistance analyzing data; interns Sarah Sakha,

Catherine Peng, Priya Pai, and Lindsey Feingold for

their assistance in research and analysis; and Neil

Shovelin, Creative Director, for his guidance with

visual design.

We appreciate Udi Ofer, Director, Justice Division,

for his edits and strategic guidance on content and

recommendations, and Lucia Tian, Chief Analytics

Officer, for her edits and strategic guidance on data

analysis and methods. We are also very grateful to

Jeff Robinson, Director, Trone Center for Justice and

Equality; ReNika Moore, Director, Racial Justice

Project; and Carl Takei, Senior Staff Attorney, Trone

Center for Justice and Equality, for their edits and

feedback.

The authors also thank Brandon Cox,

Communications Strategist, for his assistance. We

are grateful for the support from ACLU colleagues

Sondra Goldschein, Deputy Director and Director of

Program and Strategy of the Affiliate Support and

Nationwide Initiatives Department; Danielle Silber,

Director of Strategic Partnerships; and Leila Rafei,

Content Strategist.

The authors also thank ACLU affiliates for their

invaluable feedback on the development of the

report. We extend specific thanks to Michael Perloff

and Scott Michelman at the ACLU of the District of

Columbia for their efforts to obtain data from the

D.C. Metropolitan Police Department; Daniel Tilley

of the ACLU of Florida for his efforts to obtain data

from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement;

and Michelle Shames at the New York Civil Liberties

Union for her help obtaining data from the New York

City Police Department.

Graphic design for this report was provided by

Patrick Moroney.

Contents

Executive Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Key Findings.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Methodology and Limitations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Marijuana Arrests. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

The National Landscape.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

State and County Landscape.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

States That Legalized or Decriminalized Marijuana Possession. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Racial Disparities in Marijuana Arrests.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

The National Landscape.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

State and County Landscape.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

States That Legalized or Decriminalized Marijuana Possession. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Conclusion.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37

Recommendations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Federal, State, and Local Governments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

Law Enforcement Agencies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

State Profiles.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

Appendices. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

Endnotes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Executive Summary

In 2013, the ACLU published an

FINDING #1

unprecedented national report on marijuana

The War on Marijuana Rages on:

Marijuana Arrests Still Widespread

Across the U.S.

possession arrests, The War on Marijuana

in Black and White,1 analyzing data from

all 50 states (and the District of Columbia)

between 2001 and 2010. Over that time

period, law enforcement made millions of

marijuana arrests, the vast majority of which

were for possession, and Black people2 were

much more likely to be arrested than white

FINDING #2

Extreme Racial Disparities in

Marijuana Possession Arrests

Persist Throughout the Country,

and Have Not Improved Since 2010

people for marijuana possession despite

comparable usage rates. This report updates

our previous findings through an analysis of

marijuana possession arrests and attendant

FINDING #3

Marijuana Arrests Decreased after

Legalization or Decriminalization

racial disparities from 2010 to 2018, and

provides specific analysis on states that have

approved legalization and decriminalization

laws. The report relies on the Federal Bureau

of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Reporting

Program (UCR), supplementary data from

FINDING #4

Racial Disparities in Arrests Persist

Even in States That Legalized or

Decriminalized Marijuana

jurisdictions not included in UCR, and

the United States Census’ annual county

FINDING #5

population estimates to document arrest

Data Collection Failures Block a

Fuller Understanding of Racial

Disparities in Marijuana Arrests

rates per 100,000 for marijuana possession,

by race, at the state and county level.3

4

ACLU Research Report

Disturbingly, too much has remained unchanged

in the past decade despite several states having

reformed marijuana policy. While marijuana

arrests were down by 18% overall since 2010, law

enforcement still made more than 6.1 million such

arrests over the past eight years. In 2018, there were

almost 700,000 marijuana arrests, which accounted

for more than 43% of all drug arrests. In fact, in

2018, police made more marijuana arrests than

for all violent crimes combined, according to the

FBI. Further, it is not clear that marijuana arrests

are trending down—they have actually risen in the

past few years, with almost 100,000 more arrests

in 2018 than 2015. This rise in marijuana arrests

has been driven by states in which marijuana is still

illegal, whereas between 2010 and 2018, marijuana

arrests were significantly lower in states that had

legalized and went down modestly in states that had

decriminalized. Consistent with our previous report,

the majority of marijuana arrests — nine out of every

10 — were for possession.

Equally as troubling, this report finds that stark

racial disparities in marijuana possession arrests

have remained unchanged nationwide. On average, a

Black person is 3.64 times more likely to be arrested

for marijuana possession than a white person, even

though Black and white people use marijuana at

similar rates. Just as before, such racial disparities

in marijuana possession arrests exist across the

country, in every state, in counties large and small,

urban and rural, wealthy and poor, and with large

and small Black populations. Indeed, in every

state and in over 95% of counties with more than

Recommendations at a Glance

For Federal, State, and Local

Governments

• Legalize marijuana use and possession

• Do not replace marijuana prohibition

with a system of fines, fees, and arrests

• Grant clemency to or resentence anyone

incarcerated on a marijuana conviction

and expunge all marijuana convictions

For Law Enforcement Agencies

• End the enforcement of marijuana

possession and distribution

• End racial profiling by police

• Eliminate consent searches

• End the practice of using raw numbers of

stops, citations, summons, and arrests as a

metric to measure productivity and efficacy

• Eliminate collateral consequences

that result from marijuana arrests or

convictions

• Develop systems for the routine collection of

accurate data on a range of police practices

• Ensure new legal markets benefit and are

accessible to communities most harmed

by the War on Drugs

• Invest in nonpunitive programs and

community-based services and divest from

law enforcement

• Ensure marijuana possession and

other low-level offense arrests are not

included in performance measures for

federal funding

• Develop, secure, and implement strong,

independent, and effective oversight

mechanisms for local law enforcement

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

5

30,000 people in which at least 1% of the residents

are Black, Black people are arrested at higher

rates than white people for marijuana possession.

Although, on average, states that legalized marijuana

through taxation and regulation had lower rates of

racial disparities in marijuana possession arrests

(1.7x) than states where marijuana has not been

legalized (3.2x), a distressing pattern continues —

racial disparities persist in every state that has rolled

back marijuana prohibition — and in some cases,

disparities have worsened.4

This report should be the final nail in the coffin

for the inane War on Marijuana, and sound yet

another abolition knell for this country’s 45-year

drug prohibition charade. The question no longer

is whether the U.S. should legalize marijuana — it

should — or whether marijuana legalization is

about racial equity — it is. It is also no longer about

whether all levels of government should redirect

resources away from prosecution of marijuana and

toward public health investments and community

collaborations — they should. Rather, the question

is: When states legalize, how can they do so through

a racial justice lens to address the panoply of harms

that have been selectively aimed at Black and

Latinx communities for decades? These harms

include not only arrests, incarceration, and lifelong

criminal convictions, but also the loss of jobs,

housing, financial aid eligibility, child custody, and

In every state,

Black people

are arrested

at higher rates

than white people

for marijuana

possession.

6

ACLU Research Report

immigration status. This report provides a detailed

road map for ending the War on Marijuana and

ensuring legalization efforts center racial justice as

they address the widespread collateral damage.

The ACLU reaffirms its recommendation that

federal and state governments legalize marijuana

for persons 21 or older through a system of taxation,

licensing, and regulation, and urges that legalization

repair the harms that prohibition has wreaked on

communities of color.

Key Findings

FINDING #1

The War on Marijuana Rages on:

Marijuana Arrests Still Widespread

Across the U.S.

• Although marijuana arrests have decreased by

18% since 2010, that trend slowed to a halt in the

middle of the decade. There were more marijuana

arrests in 2018 than in 2015, despite the fact that

eight states legalized marijuana for recreational

use or decriminalized marijuana possession in

that timeframe.

• In general, states that have legalized or

decriminalized marijuana possession have seen

a decline in marijuana possession arrests, but in

many other states, arrest rates have increased or

remain unchanged.

• Marijuana arrests made up 43% of all drug arrests

in 2018, more than any other drug category. While

that percentage has dropped from just over 50%

in 2010, this is due in part to a steady increase in

arrests in other drug categories.

• The overwhelming majority of marijuana arrests —

89.6% — are for possession only.

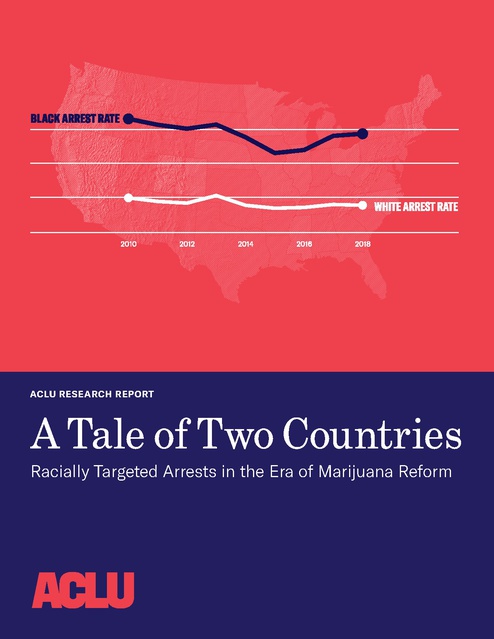

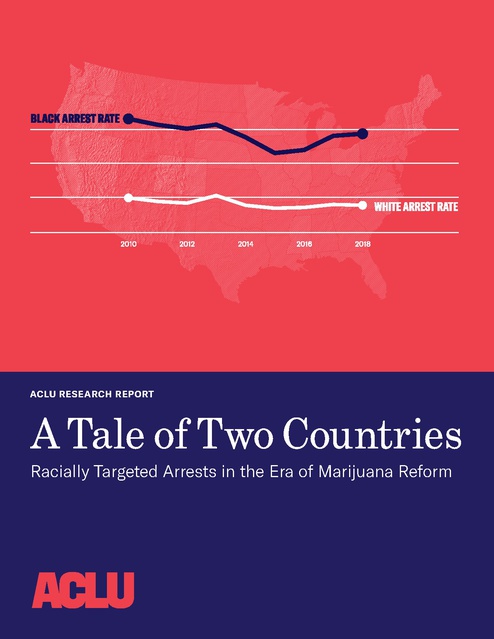

Rates of Black and White Marijuana Possession

Arrests per 100k People

Black arrest rate

600

400

White arrest rate

200

0

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data

Note: Florida and Washington, D.C. did not provide data.

FINDING #2

Extreme Racial Disparities in

Marijuana Possession Arrests Persist

Throughout the Country and Have

Not Improved Since 2010.

• Black people are 3.64 times more likely than

white people to be arrested for marijuana

possession, notwithstanding comparable usage

rates. The increasing number of states legalizing

or decriminalizing marijuana has not reduced

national trends in racial disparities, which remain

unchanged since 2010.

• While national arrest rates for marijuana

possession were lower in 2018 than in 2010

for both Black and white individuals, racial

disparities in those arrests have not improved,

and in some jurisdictions, they have worsened.

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

7

• In every single state, Black people were more likely

to be arrested for marijuana possession, and in

some states, Black people were up to six, eight, or

almost 10 times more likely to be arrested. In 31

states, racial disparities were actually larger in

2018 than they were in 2010.

• Montana, Kentucky, Illinois, West Virginia,

and Iowa were the states with the highest racial

disparities in marijuana possession arrest rates

(9.62, 9.36, 7.51, 7.31, and 7.26 respectively).

FINDING #3

Marijuana Arrests Decreased After

Legalization or Decriminalization,

But There Was Significant

Variability Across States That Only

Decriminalized.

• Arrests for marijuana possession decreased

over time (from 2010–2018) in all states that

legalized recreational marijuana possession.

In some states, these decreases clearly began

after legalization (Colorado, Maine, Nevada). In

other legalized states, decreases continued on a

downward trend that had begun pre-legalization

(Alaska, Oregon, Washington). In two states

(California, Massachusetts), though there was

a decline in arrests from 2010–2018, there was

little change after legalization. In these states, the

decrease in arrests occurred prior to legalization

and remained low, perhaps due to earlier

decriminalization.

• Overall, arrests for marijuana possession also

fell slightly between 2010–2018 in states that

had decriminalized but not legalized recreational

marijuana. However, there is significant

variability across states — and in one state

(Missouri), arrest rates actually increased after

decriminalization. Marijuana possession arrest

rates were approximately eight times higher in

decriminalized states than in legalized states,

although lower than in states where marijuana

possession remained illegal.

8

ACLU Research Report

• In legalized states, arrests for marijuana sales also

decreased greatly from 2010 to 2018 (81.3%). Sales

arrest rates also dropped in decriminalized states,

although to a lesser degree (33.6%).

FINDING #4

Racial Disparities in Arrests Persist

Even in States That Legalized or

Decriminalized Marijuana.

• Although the total number of people arrested

for marijuana possession, and rates of arrests,

have decreased in all legalized states and most

decriminalized states for both Black and white

people, the racial disparities in arrest rates in

these states remain. Specifically, in every state

that has legalized or decriminalized marijuana

possession, Black people are still more likely to be

arrested for possession than white people.

• In some legalized states, such as Maine and

Massachusetts, the racial disparities in marijuana

possession arrests were larger in 2018 than in

2010. In other legalized states, such as California

and Nevada, the disparities narrowed, although

Black people were still more likely to be arrested

for marijuana possession than white people.

• On average, states that have legalized marijuana

possession had lower racial disparities in

possession arrests in 2018 compared both to

states that have only decriminalized and states

where marijuana remains illegal. However, it is not

clear that this difference is a result of legalization

– these states also had lower racial disparities in

2010, before any states had legalized.

FINDING #5

Data Collection Failures Block a

Fuller Understanding of Racial

Disparities in Marijuana Arrests.

• Although a great body of evidence establishes that

Latinx individuals face racial bias in policing and

discrimination in the criminal legal system writ

large, we were not able to compare marijuana

arrest rates for Latinx individuals in this report.

• The FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting arrest

data is the most up-to-date and comprehensive

data on arrests nationally, by state, and by

county. However, similar to many federal data

collection efforts, UCR data fails to disaggregate

between Latinx individuals of different races,

making it impossible to distinguish between

Latinx and non-Latinx individuals in the Black

and white populations. Because UCR data does

not identify Latinx populations as a distinct racial

group, potential disparities in arrest rates for

Latinx populations cannot be examined. Arrests of

Latinx individuals coded as white in the data likely

artificially inflate the number of white arrests,

leading to an underestimate of the disparity

between Black and white arrest rates.5

• In addition to their impact on Black and Latinx

populations, other racial or ethnic groups may

be affected by bias in policing and marijuana

enforcement. Future research using UCR data is

warranted to examine disparities for Native and

Indigenous populations, and Asian and Pacific

Islander populations, particularly in jurisdictions

with large enough samples of these populations.

However, disparities for bi- or multiracial people

cannot be examined with UCR data because the

UCR Program employs a “check one” approach

to race, and does not allow for an individual to

be coded as more than one race. Furthermore,

disparities for Arab and Middle Eastern people

cannot be examined with UCR data as they are not

identified by the UCR Program at all.

• The variation in reporting quality across years,

agencies, and geographies also leaves some gaps

in some constituents’ ability to quantify racial

disparities at the local level.

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

9

Introduction

The criminalization of marijuana and the “War on Drugs” more broadly has been a

misinformed and racist government campaign that continues to result in the criminalization

of millions of Americans.6 Pursued under the guise of public safety and reducing marijuana

consumption, this decades-long debacle has been an abject failure — it has harmed

communities, needlessly derailed lives, and wasted taxpayers’ valuable dollars. Both public

opinion and sage public policy have called for an end to marijuana prohibition. In response,

several states have legalized or decriminalized marijuana use in recent years. As of March

2020, 11 states and Washington, D.C.7, have legalized the recreational consumption of

marijuana, and in 2019, Hawai‘i became the 15th state to reduce the criminal consequences of

marijuana-related offenses.8

A growing body of research has sought to explore the

impact of these reforms, finding that these reforms

led to a reduction in marijuana-related arrests and

the myriad harmful consequences associated with

a criminal conviction.9 However, research suggests

that racial disparities in marijuana arrests persist

in several of those states, remaining as sharp a

thorn in the nation’s side as they were a decade ago.10

Moreover, according to the FBI, after an overall dip in

the number of marijuana arrests between 2010–2014,

such arrests began to increase again, and there were

roughly 100,000 more marijuana arrests in 2018 than

in 2015.11 This report seeks to build on this existing

research — as well as our 2013 report The War on

Marijuana in Black and White12 — to document the

national, state, and local landscape; to assess our

progress; and to examine the potential promise of

reforms. As this report will demonstrate, much of this

country has yet to start on the road toward equitable,

smart, reparative marijuana policy, and for those

that have, the journey is not complete.

10

ACLU Research Report

The War on Marijuana

In our 2013 report The War on Marijuana in Black

and White, we documented the national scope of our

country’s decades-long, multibillion-dollar, racist war

against people who use marijuana. We found that, in

2010, despite the fact that Black and white people13

use marijuana at similar rates, Black people were

arrested at over three times the rate of white people,

and up to eight times as often in some states. Further,

such racial disparities increased between 2001 and

2010, as did marijuana possession arrests overall.

Such wasteful and race-driven enforcement of

marijuana laws did not occur overnight. Since

the early decades of the 20th century, the

criminalization of marijuana has been a pretext

for the criminalization of Black and Brown people.14

Taking advantage of several decades of Reefer

Madness propaganda, in 1970, President Richard

Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act and

classified marijuana under Schedule I — reserved

for the most dangerous class of drugs with

the highest potential for abuse and little to no

medical value, a designation shared by drugs like

heroin, methamphetamines, and PCP. But such

classification — like the drug war generally — had

nothing to do with marijuana or science, and

everything to do with criminalizing and controlling

certain communities. As John Ehrlichman, counsel

to Nixon and assistant to the president for domestic

affairs, said over two decades later:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be

against the war (Vietnam) or Black, but by

getting the public to associate the hippies with

marijuana and the Blacks with heroin, and

then criminalizing both heavily, we could

disrupt those communities. We could arrest

their leaders, raid their homes, break up their

meetings, and vilify them night after night on

the evening news. Did we know we were lying

about the drugs? Of course we did.”15

This war on people who use drugs has since been

declared a failure by countless public health

officials and advocacy organizations, the World

Health Organization, and the United Nations.16 In

response, certain countries have pursued nationwide

legalization of marijuana, while many jurisdictions

across the U.S. have decriminalized or legalized

marijuana for both recreational and medicinal use.17

Despite the often bipartisan groundswell to legalize

marijuana use, and the fact that two in every three

Americans support legalizing marijuana,18 marijuana

remains illegal in a majority of states.

Inconsistency at the

Federal Level

At the federal level, marijuana remains a Schedule I

substance, subjecting people involved in marijuana

activities to harsh penalties and preventing a range

of scientific research that could upend decades of

propagandized misinformation driven by racism

and fear.

Much of this

country has yet to

start on the road

toward equitable,

smart, reparative

marijuana policy.

Making matters worse, the Trump administration

has sought to abandon the Obama administration’s

more sensible approach to marijuana policy

by resurrecting the saber-rattling of bygone

anti-marijuana crusaders. Under the Obama

administration, local jurisdictions enjoyed

substantial deference with regard to setting

marijuana policy. In 2013, Deputy Attorney

General James Cole issued a guideline (“The

Cole Memorandum”) significantly limiting the

enforcement of federal marijuana laws in states that

had legalized.19 Such deference to states that were

experimenting with legalization was crucial for the

vitality of the newly legalized markets. Consumers

needed to feel safe participating in marijuana

activities, and entrepreneurs needed to know that

the federal government was not about to shut down

their ventures or prosecute them for engaging in

business that was legal in their state. The Obama

administration’s approach reassured states that the

federal government would not interfere with states’

legalization efforts as long as those efforts did not

implicate federal enforcement priorities, such as

interstate drug trafficking and drug cartels.20

Rather than respecting the will of the voters in states

that legalized marijuana, the Trump administration

and its first attorney general, Jeff Sessions (who,

when he was a U.S. Senator, famously proclaimed,

“Good people don’t smoke marijuana”), promptly

rescinded this policy. The same week that California

began selling and taxing marijuana for recreational

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

11

use21 and Vermont’s legislature called for a formal

vote on its own legalization bill,22 the Department

of Justice announced that the Cole Memorandum

was no longer in effect. Instead, Attorney General

Sessions, echoing discredited alarmists of yesterday,

asserted that “marijuana is a dangerous drug and

that marijuana activity is a serious crime”23 and

instructed federal prosecutors “to use previously

established prosecutorial principles that provide

them all the necessary tools to disrupt criminal

organizations, tackle the growing drug crisis, and

thwart violent crime across our country.”

Notwithstanding Sessions’ peddling of prohibitionist,

time-worn rhetoric, most Americans support

legalizing marijuana. Furthermore, state-level

efforts to get smart on marijuana continue, and

federal marijuana prosecutions are declining.24

Even Sessions’ replacement, Attorney General

William Barr, recently communicated to members

of Congress that he would support a carve-out

exemption that would protect states from federal

prosecution if they legalized recreational marijuana

consumption.25

In spite of this ongoing sea change, law enforcement

in the U.S. continues to make hundreds of thousands

of marijuana arrests every year, and Black people

continue to bear the disproportionate brunt of those

arrests. Marijuana legalization should be — and

indeed is — a racial justice issue. But thus far, racial

justice has largely been a peripheral or incidental

goal of legalization, resulting in continued racist

enforcement of marijuana laws, the exclusion of

Thus far, racial

justice has largely

been a peripheral

or incidental goal of

legalization.

12

ACLU Research Report

people of color from participating in, leading, and

building wealth from the marijuana industry, and the

failure to repair the harms done to communities of

color by the drug war. 26

Centering Racial Justice

Marijuana legalization has always been a racial

justice issue.27 Whereas marijuana use by white

people has been de facto legal in much of the country,

in Black and Brown communities, police have

routinely stopped people, particularly youth — at

the park, on the street, in the train, on the bus, at

school, near school, by the community center, on the

porch, or while driving — searching (usually in vain)

for something illegal, and, if they found marijuana,

arresting and hauling people to jail.28 Such police

harassment not only criminalizes people of color for

engaging in an activity that white people participate

in with relative impunity, it is a means of surveillance

and social control29 counterproductive to public

safety and community health. Indeed, repeated police

encounters prove traumatic and dehumanizing for

those who endure them.30

Simply put, marijuana is used at similar rates by

Black and white people across America,31 yet Black

and Brown people are disproportionately targeted

for and harmed by its criminalization, subjected to

stops, frisks, arrests, and convictions of marijuanarelated offenses because of their race. This is true

for drug enforcement generally (see crack versus

cocaine enforcement and sentencing) but perhaps

no more starkly than when it comes to marijuana

enforcement.32

While some states that have legalized marijuana

built expungement, resentencing, and

reclassification mechanisms into their reforms

to ensure that people previously convicted of

marijuana violations benefit retroactively from

marijuana’s legal status, their effectiveness in

reducing the disparate harm on people of color

remains unclear. Furthermore, other states

have not centered racial equity in their reforms,

and much more can be done to guarantee that

drug reform laws repair the harms suffered by

communities of color as a result of racially biased

enforcement and criminalization. Precisely because

of this history, racial justice remains a critical

prism through which drug reform policies should be

evaluated.33

Reforms Beyond Legislation:

The Role of Prosecutors and

Police

To be sure, while legalization is the most powerful

step toward reducing the damage of marijuana

criminalization, there are other steps that can

be taken in the meantime. For example, local

prosecutors have the power to end prosecution for

marijuana violations. Cyrus Vance, the district

attorney for Manhattan, instituted a Decline-toProsecute policy on marijuana possession and

consumption cases, reportedly resulting in a

substantial reduction of such cases in the first 90 days

of the policy taking effect.34 District Attorney Larry

Krasner of Philadelphia, State’s Attorney Marilyn

Mosby of Baltimore, Fairfax County Commonwealth

Attorney Steve Descano of Virginia, Cook County

State’s Attorney Kim Foxx of Illinois, and a growing

list of prosecutors have launched similar efforts in

order to discontinue the harmful approaches of their

predecessors on marijuana policy.

While they ameliorate the harm of criminal

prosecutions, such approaches cannot be successful

in reducing the harm caused to individuals subject

to marijuana arrests if police departments are not

partners in the prosecutors’ efforts. For example,

after the Austin, Texas, City Council passed a

resolution to reduce arrests for low-level marijuana

violations, the local police chief quickly rebuffed

legislators and vowed to continue to enforce the police

department’s policy of arresting or issuing citations

for marijuana violations.35 Conversely, in Seattle, the

police department played a critical role in minimizing

the harms of marijuana criminalization.36

Of course, progressive policies toward marijuana

enforcement can only be effective if they are part

of a broader effort by prosecutors and police to end

selective enforcement of all criminal laws against

Black and Brown people. After all, marijuana

prohibition is simply one tool in governments’

criminal law arsenal — albeit a very effective and

ubiquitous one — to marginalize and disempower

people of color.

Criminal consequences is not the only harm

of marijuana prohibition. There is a range of

potentially debilitating collateral consequences as

well, many of which persist even after marijuana is

decriminalized or even legalized. These can further

erode people’s civil rights by impacting housing

rights, parental rights, the administration of public

benefits, access to education, and immigration

status. For example, families who live in federally

subsidized public housing face eviction or family

separation if someone is accused of using marijuana

on their premises. Parents may lose their children

in family court proceedings if accused of using

marijuana. Disabled and poor recipients of public

benefits still face the threat of losing their benefits

for marijuana use. Immigrants can face deportation

for marijuana use. Because of the race-driven way in

which marijuana criminal laws have been enforced,

each of these potentially life-altering consequences of

criminalization has been borne disproportionately by

communities of color.

Conclusion

In 2020, we enter a decade marked by confusion

and contradictions when it comes to marijuana

policies. Today, marijuana is still categorized by

the federal government among the most dangerous

drugs with no medicinal value, and yet 37 states

have rolled back prohibitionist laws (11 states and

the District of Columbia have legalized recreational

use, 15 other states have decriminalized use, and

11 additional states have legalized it for medical

use only).37 People in neighboring states, such as

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

13

Illinois and Wisconsin, enjoy markedly different

rights given the conflicting legal status of marijuana

across their borders.38 Traveling from Illinois to

Wisconsin, someone who uses marijuana goes from

being a casual consumer protected by local law to

a potential target of criminal laws subject to lifealtering prosecution. And the injustice of the past

is a harbinger for today’s marijuana market. While

corporations, entrepreneurs, and governments in

some jurisdictions are making millions of dollars

in profits and revenues in the legal marijuana

industry, poor people in other jurisdictions are stuck

in handcuffs or jail cells, or with lifelong criminal

records for possessing or selling miniscule fractions

of what these powerful companies move daily. In

some states, there are even people serving sentences

of life without parole for marijuana convictions.39

Clearly, there is a long way to go to end the harms

of marijuana prohibition and ensure that racial

equity guides the implementation of legalization and

decriminalization efforts.

As we begin a new decade, it is time to assess the

progress and failures of this country’s marijuana

policies at the state and county level with regard

to racial justice. This report provides a new,

unprecedented examination of the state of marijuana

enforcement in the U.S. and the ramifications of

decriminalization and legalization efforts — on overall

arrests, and specifically on the racial inequities

perpetuated by this war. Using data on marijuana

arrests that local police departments provide the

FBI under the Uniform Crime Reporting Program,

alongside supplemented data obtained directly from

unreported jurisdictions, this report examines

nationwide and state trends in both arrests and

Black/white racial disparities. Keenly aware of the

consequential policy decisions made at local levels,

this report also examines how different counties

behave with respect to marijuana arrests and racial

disparities in such arrests. And as the number of

states implementing reforms in marijuana laws

has increased since our last report, we are able

to examine the potential impact legalization or

14

ACLU Research Report

This report

provides a new,

unprecedented

examination of the

state of marijuana

enforcement in

the U.S.

decriminalization policies have had on such arrests

and racial disparities.

Indeed, while there is some existing research

examining the potential fiscal and public safety

impacts of marijuana law reforms in select states

or jurisdictions, there is considerably less empirical

research on the impact of these reforms on people

of color. The scope of this report not only allows

for an examination of the national, state, and

local landscapes, it will provide new information

on the success — or failure — of these current laws

to address the racial inequities perpetuated by

marijuana prohibitions. As such, these findings offer

direction for policymakers, criminal justice leaders,

and advocates who seek not only to end the war on

marijuana, but to ensure that we do so in reparative

ways that allow us to confront the racial injustice

of the past by building a path forward with and for

the people and communities most deeply harmed by

marijuana prohibition.

Methodology and

Limitations

To document the incidence of marijuana and other drug arrests, this report uses data from

the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, supplemented by data obtained directly

from states, when necessary (i.e., Illinois, New York). The data is used descriptively to better

understand marijuana arrest patterns over time. In this section we describe our data sources,

usage, and limitations.

Data

• Uniform Crime Reporting Data [United

States]: Summarized Agency Data, 20172018. These datasets are publicly available

through the FBI’s Crime Data API.

Sources

The marijuana possession arrest data presented

in this report was obtained from the FBI’s Uniform

Crime Reporting Program (UCR) Program. For the

years 2010–2016, the data was obtained through the

National Archive of Criminal Justice Data (NACJD).

We downloaded tables of data that included monthly

counts of each offense type for each agency that

reports to the UCR Program, for each racial group.

For the years 2017 and 2018, data was not available

through NACJD at the time of analysis. For these

years, we used the FBI’s Automated Programming

Interface (API) to retrieve the data. Data for

years 2017 and 2018 was last retrieved via API on

November 22, 2019.

• Uniform Crime Reporting Data [United

States]: Arrests by Age, Sex, and Race

[Alternative Title: ASR], 2011-2016. These

datasets are publicly available through the NACJD

and stored at the Inter-university Consortium for

Political and Social Research at the University of

Michigan.

In addition, population estimates for each county for

each year were obtained from:

• U.S. Census Bureau, “Annual County

Resident Population Estimates by Age, Sex,

Race, and Hispanic Origin,” April 1, 2010,

to July 1, 2018. This data was released in

June 2019 by the population division of the U.S.

Census Bureau. Raw data is available in CSV

format here, and a data dictionary describing the

variable definitions is available here. This dataset

estimates the population of each racial group of

each county on July 1 of the corresponding year.

While most states report to the UCR Program, some

do not, and thus data for Illinois and New York City

were obtained separately. We obtained arrest data for

New York City from “NYPD Arrests Data” (Historic),

published by the New York Police Department online

at NYC OpenData. This data was last updated on

May 16, 2019. Data for Illinois was obtained through

a Freedom of Information Act, 5 ILCS 140 (“FOIA”)

request submitted to the Illinois Department of

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

15

State Police, which acts as the central repository and

custodian for crime statistics from every policing

body in Illinois.

We also submitted FOIA requests to Washington,

D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD),

as well as to the Florida Department of Law

Enforcement, in November 2019. In December 2019,

Washington, D.C.’s Mayor’s Office of Legal Counsel

ruled in favor of a legal appeal submitted by the ACLU

and ordered MPD to begin producing responsive

records within five business days. Nevertheless,

the District of Columbia did not provide data in an

appropriate, timely manner for analysis in this report,

and Florida refused to provide any data at all.

Counting and Classifying Marijuana Arrests

The data used in this report (both UCR data and

supplementary state data) count one arrest for each

separate instance in which a person is arrested,

cited, or summoned for an offense. Because a person

may be arrested more than once in a year, the arrest

numbers used in this report do not reflect the actual

number of individuals who have been arrested; rather,

the arrest data shows the total number of times

that persons have been arrested, as reported by law

enforcement agencies to the UCR Program.

When someone is arrested for multiple crimes arising

from a single police interaction, the UCR Program

calls it a “multiple-offense situation.” As a general

rule, a multiple-offense situation requires classifying

each of the offenses committed into “Part I” and

“non-Part I” offenses. Part I offenses are the following:

Murder, Rape, Robbery, Aggravated Assault,

Burglary, Larceny (theft), Motor Vehicle Theft, and

Arson (fire). Marijuana possession is defined as a nonPart I offense, as are all drug offenses. The Hierarchy

Rule, as described in the FBI/UCR Handbook,

requires that in a multiple-offense situation involving

both Part I (e.g., Robbery — Other Dangerous

Weapon) and non-Part I offenses (e.g., Marijuana —

Possession), only the Part I offense, Robbery — Other

Dangerous Weapon, is classified and reported.

16

ACLU Research Report

The arrest for marijuana possession would not be

reported in this situation. Additionally, if a person is

arrested for multiple Part II offenses, the reporting

agency determines which offense is the most serious

and scores only that arrest. Thus, any marijuana

possession arrest recorded in the UCR data is an

arrest in which marijuana possession is the highest

charge for which that individual was arrested during

that police interaction. Any racial disparity observed

in marijuana arrests recorded in UCR data is thus not

a product of differential arrest rates for Part I crimes

or crimes that agencies deem more serious than

marijuana possession. According to the FBI, more

than 85% of all arrests are for a single offense.

It should be noted that for data obtained from New

York City, the New York Police Department publishes

a data footnote that states, “Only valid arrests are

included in this release. Arrests that were voided

when further investigation reveals person did not

commit offense or it is determined no offense has

been committed are excluded from the data set.” As

such, NYC data may not be directly comparable to

other agencies that include arrests that were not

excluded from the dataset. Individual nuances in the

way police departments categorize arrests, due to

differences in state law, enforcement priorities, and

reporting capacity, are inherent in any interpretation

of UCR data, and will be discussed more in the

limitations section below.

Coverage

The UCR Arrests by Age, Sex, and Race dataset and

the Summarized Agency Data from the UCR API

include variables that indicate the population covered

by a particular agency. The FBI also provides an

“Agency Crosswalk file,” which shows which agencies

correspond to each county. To find each county total,

we summarized the total number of arrests and

the total population within each county. We then

compared the population of all the agencies reporting

data in a particular county to the total population of

that county to identify a coverage indicator.

The coverage indicator is a measure of how

completely the agencies within a given county have

reported their arrests to the UCR Program. For

each agency, we multiply the population covered by

that agency by the number of months reported, and

divide by 12. For example, if an agency that covered

50,000 people reported data for 12 out of 12 months,

the “reported population” of that agency is 50,000 *

12 / 12, or 50,000. However, if that same agency only

reported data for 10 out of 12 months of the year, its

reported population is 50,000 * 10 / 12, or 41,667.

Participation in the UCR Program varies widely.

Many counties have full participation, with all

local enforcement agencies in the county reporting

to the UCR Program, but some agencies within

some counties do not report data, or do not report

every month, due at times to budget and capacity

constraints. If an agency reports data for fewer than

12 months, we used the FBI’s methodology, described

below, to impute the missing arrest counts.

We impute data at the agency level, and summarize

coverage at the county level to get a coverage

indicator, or a measure of the countywide data

quality. While many counties have a coverage

indicator of 100%, some counties have missing

data, and the more data a county is missing, the less

confidence we can have in our estimates. If a county is

less than 50% covered, meaning that more than half

of its data is imputed, we do not report its individual

arrest counts or arrest rate estimates.

Imputation

The National Archive of Criminal Justice Data

(NACJD), part of the Inter-university Consortium

for Political and Social Research, imputes data for

missing agencies to aggregate to the county level.

We use the same procedure but also aggregate by

race to be able to examine racial disparities. Their

imputation procedure is described in full here, but

in brief, the following steps are used to estimate the

number of arrests for agencies with various types

of reporting procedures. First, data for any agency

reporting 12 full months is submitted as-is. Second,

data for an agency reporting three to 11 months is

multiplied by a weight of [12/months reported]. For

example, if an agency reports 50 arrests over six

months of data, 50 is multiplied by 12/6 (or 2) to

estimate that 100 arrests would have occurred over

a similar 12-month period. For agencies reporting

zero to two months, data is too sparse to be reliable.

These are first set to zero, and then data is estimated

using rates calculated from fully reporting agencies

located in the missing agency’s state and geographic

stratum. More about defining the geographic strata

is described by the NACJD, but, briefly, if an agency

covering a population of 15,000 fails to report data

to the UCR, then the arrest total for that agency is

imputed using the average number of arrests among

similarly sized agencies in the same state and year.

Finally, that agency-level data is aggregated to

the county level using the crosswalk file. The total

county-level reported population is aggregated and

divided by the county-level total population, including

nonreporting agencies, to arrive at the county-level

coverage indicator. Throughout this analysis, when

highlighting individual counties, we exclude counties

with a coverage of less than 50% — that is, counties

where arrests were imputed for more than 50% of

the population covered in that county. For example,

in 2018, 12.6% (381) of counties had less than 50%

coverage and were thus excluded from these analyses.

Though analysis of raw data undercounts the total

arrest counts because of agencies that do not report,

the results on the impacts of racial disparities

do not substantially vary from the results using

the methodology from our 2013 report. Thus,

for consistency with NACJD, we use the UCR’s

imputation methodology for this report.

Calculating Rate Ratios

Racial disparities in policing and enforcement of

marijuana possession laws can be quantified by

comparing arrest rates in the Black population to

arrest rates in the white population. By dividing the

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

17

rate in the Black population by the rate in the white

population, we can estimate if Black people are more

likely than white people to be arrested for marijuana

possession, and, if so, how much more likely. Below is

the formula used to calculate the rate ratio:

RR=Ba/Bp / Wa/Wp

Where RR is the Black-to-white rate ratio of arrests

for marijuana possession; Ba/Bp is the rate of arrest

in the Black population, and Wa/Wp is the rate of

arrest in the white population.

State Profiles

We used the following additional methods for the 49

state profile sheets included at the end of this report.

When identifying the top counties with the largest

racial disparities per state, we generally only included

counties with: a population of at least 30,000, a Black

population of at least 1%, a data coverage ratio of

at least 50%, and at least 25 arrests for marijuana

possession. We applied this inclusion criteria to

avoid highlighting counties with outlier rates due

to very small populations and numbers of arrests.

Because states vary widely in their demographics, it

was imperative to modify the inclusion criteria in

select cases, which are also noted in each state profile

sheet. For states with less than a 1% Black population

overall, we included counties for the ranking if they

met all criteria outside of the Black population

criterion. We extended this rule to Hawai‘i, where

we only obtained data for two counties. In Vermont,

very few counties made more than 25 marijuana

possession arrests in 2018, so we lowered that cutoff

to 10 marijuana possession arrests. Additionally,

because Alaska is less densely populated, we

broadened the population criteria to include counties

in Alaska with a population of at least 20,000 and

at least 10 marijuana possession arrests. Those

counties were excluded from consideration when

identifying the top counties per state with largest

racial disparities, but were included in other aspects

of analyses for the state profiles and the entire report.

18

ACLU Research Report

Each state profile includes a county-level map.

On that map, counties for which we received no

data (roughly 50 counties across all 49 states) are

indicated by stripes. In addition, there were five

counties that arrested multiple Black people for

marijuana possession and zero white people. The

measure of racial disparities in these counties is

mathematically infinite, so while we do not report

numeric rate ratios for these counties, they are

colored in red in the county-level maps, indicating

racial disparities above the national average.

Similarly, the counties that reported zero Black and

white possession arrests (roughly 125 counties) are

colored in grey, indicating racial disparities below the

national average.

Limitations and Considerations

This report, which analyzes data from 2010–2018,

in combination with our previous report assessing

data from 2000–2010, offers an unprecedented

look at the national, state, and county landscape

of marijuana enforcement over the past nearly two

decades. However, as with all research, there are

some limitations to the data. Here we present those

limitations, along with a few key areas to consider

when interpreting the findings of this report.

Limitations of Missing Data

The ambition of the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting

Program in attempting to harmonize arrest data

from more than 18,000 agencies across the country

makes it the most comprehensive data source for

understanding arrests in the U.S., but gaps remain.

This section describes our attempts to deal with

those gaps, their comparability to UCR data, and the

extensibility of this analysis to previous work.

As mentioned previously, not every agency reports

data for each month. The imputation method

described previously is used by the FBI to fill in

gaps in county-level crime data, but these methods

are simple and do not account for fundamental

differences between reporting agencies and

nonreporting agencies. Though a majority of the

FBI’s agencies and an even larger majority of the

agencies covering large populations like cities

had 100% coverage in the years we analyzed, we

were unable to determine whether systematic

biases existed between reporting agencies and

nonreporting agencies with regard to population

demographics. The lowest unit of measurement at

which demographic data by race was available was

the county level, not the agency level. It is conceivable

that the demographics of agencies with full UCR

reporting are different from those with little or no

UCR reporting. If arrest rates in populations in

these nonreporting agencies differ systematically

from arrest rates in reporting agencies, it is likely

that our estimates are imprecise. Systematic

differences could bias the results of our analysis in

either direction. However, given the consistency

of the racial disparities in every state and nearly

every county in the nation, we feel that despite this

variation in agency reporting, additional data is

unlikely to change the direction of the findings — that

is, to remove the measured effect of racial disparities.

Nevertheless, we do not report estimates for counties

in which less than 50% of the population is covered by

a reporting agency.

We use a different imputation methodology in this

report than was used in our previous report, which

was published in 2013. Our imputation procedure

follows the FBI’s procedure exactly, while the

previous study used a weighting procedure at the

county level rather than imputation at the agency

level to account for missing data. The outcomes do

not change substantially whether one uses countylevel weighting or agency-level imputation, so we

selected the better-known procedure for this report

to ensure our methodology is more transparent and

replicable. For the same reasons, we provide access

to the data and code with this updated report. This

report’s methodology differs only in minor ways from

those of the earlier report, but we present 2010 data

here for comparison in the states and counties where

the methodology implemented here results in slightly

different values than in our previous report. For the

purposes of examining trends between 2000 and 2018,

these two reports can go hand-in-hand, but it is not a

goal for our 2010 estimates of racial disparities in this

report to perfectly match those used with a different

imputation methodology. Rather, the consistent

overall findings between the two reports, despite

the slight variations in methodology, are a signal

that these findings are robust to multiple different

imputation methods.

Despite our repeated attempts (as detailed

previously) to obtain data from every jurisdiction for

this report, including those that do not report to the

FBI’s UCR program, we were unable to do so. The

District of Columbia refused to provide data in an

appropriate, timely manner for analysis in this report,

and Florida refused to provide any data at all. Thus,

findings from this report are limited to 49 of the 50

U.S. states.

Race and Ethnicity Data Limitations

Although nationwide the criminalization of

marijuana has been largely targeted at Black and

Latinx individuals, UCR data only allows for an

exploration of disparities between Black and white

people, and not between Latinx and white people.

Similar to many federal data collection efforts,

UCR data does not identify Latinx individuals as a

distinct racial group, but as an ethnicity. “Ethnicity”

variables are available in UCR data codebooks,

ostensibly to distinguish between Hispanic and nonHispanic individuals of each race, but these variables

are missing so frequently that we were unable

to employ them in this analysis. As such, Latinx

individuals of all races are likely miscoded in various

ways. While Afro-Latinx people are likely to be coded

as Black in policing data and treated as Black by

police, non-Black Latinx people may often be counted

as white by reporting agencies. This miscoding

likely leads to an underestimation of the true rate

of racial disparities experienced by people of color

at the hands of police. Arrests of Latinx individuals

coded as white in the data likely artificially

inflate the number of white arrests, leading to an

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

19

underestimation of the disparity between Black and

white arrest rates.

We are mindful that in addition to Black and Latinx

groups, racial bias in policing and drug enforcement

may negatively affect other racial or ethnic groups,

such as Native and Indigenous populations, Arab

and Middle Eastern populations, Asian populations,

Pacific Islander populations, and those with multiple

racial/ethnic identities (e.g., biracial), among others.

The UCR data classifies individuals’ race as “Black,”

“white,” “Asian,” “American Indian or Alaska Native,”

“Native Hawaiian,” or “unknown.” As such, future

research using UCR data could examine racial

disparities beyond just Black and white populations,

and such analysis might be particularly warranted

in jurisdictions with significantly large populations

of those who have experienced racially biased

policing — for example, examination of disparities in

arrest rates between Native Americans and whites

in Montana. Disparities for bi- or multiracial people

cannot be examined with UCR data, however. The

UCR Program employs a “check one” approach

to race, and does not allow for an individual to be

coded as more than one race. Furthermore, Arab

and Middle Eastern people are not identified by the

UCR Program. Thus, researchers must turn to other

data sources in order to examine arrest rates for

multiracial and Arab or Middle Eastern individuals.

Considerations about Causality

This report presents descriptive statistics, providing

information about numbers of arrests, rates of

arrests, and racial disparities in those rates. Though

we provide this information for states that have

legalized and decriminalized marijuana — both before

and after these reforms were enacted — we have not

performed the requisite statistical controls that

would be required to establish a causal link between

these laws and the subsequent changes in arrest

rates and racial disparities. Indeed, in many states

and counties, arrest rates dropped between 2010

and 2018 despite the fact that marijuana possession

remained illegal in these localities, demonstrating

that many other factors besides legalization drive

20

ACLU Research Report

arrest rates. Further research, both quantitative and

qualitative, is warranted to more clearly understand

and document the effects of marijuana reforms, and

may be best done at the individual state and/or

county level.

Considerations about Timeframe

This report examines arrest rates from 2010

through 2018. Although 2018 was the most recent

year in which data was available, it still did not

allow for an examination of the present state of

marijuana enforcement. Inevitably, data analyses

and reporting must always lag somewhat behind,

preventing any research from being as current as

desired; as such, the findings provided in this report

can only reflect practices as of 2018. In 2018 and

2019, three states (Vermont, Michigan, and Illinois)

legalized marijuana possession, and three others

(Hawai‘i, New York, and New Mexico) decriminalized

possession. As data is made available for 2019 and

subsequent years, future analysis is warranted to

explore the potential effects of the more recent laws

as well as the longer-term impacts of pre-2018 laws.

Marijuana Arrests

Despite an increasing number of states legalizing or decriminalizing marijuana, law

enforcement made well over half a million marijuana arrests in 2018, more than for any

other drug, and more than for all violent crimes combined as reported by the FBI.40 As

expected, states that have legalized or decriminalized marijuana possession have seen

a decline in marijuana possession arrests. However, as of 2018, the national downward

trend appears to have leveled off, even as the number of states that have legalized or

decriminalized marijuana has increased.

The National Landscape

As indicated in Figure 1, between 2010 and 2018,

marijuana arrests in the U.S. trended weakly

downward, with rebounds in 2013, 2016, and

2017. By 2018, arrest rates were higher than in

2015, despite additional states having legalized

and decriminalized during that timeframe. In

no year did they drop below 500,000. In 2018

alone, there were an estimated 692,965 marijuana

arrests — the vast majority of which (89.6%) were

for possession (see Figure 2). As shown in Figure

3, marijuana possession arrest rates have dropped

by approximately 15% from 2010 to 2018, resulting

in a decrease in the national arrest possession

rate, from 250.52 per 100,000 in 2010 to 203.88 per

FIGURE 1

National Arrests for Marijuana and All Other

Drugs (2010–2018)

All other drug arrests

900,000

800,000

700,000

600,000

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data

Note: Florida and Washington, D.C. did not provide data.

FIGURE 2

National Arrests for Marijuana Possession and

Sales (2010–2018)

100,000 people in 2018.

As shown in Figure 4, marijuana arrests still

account for more drug arrests in the U.S. than

any other drug class.41 Marijuana arrests also

accounts for more arrests than for all violent crime

combined.42 In 2018, 43.2% of all drug arrests were

for marijuana offenses (see Table 1).

600,000

400,000

200,000

Marijuana sales

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data

Note: Florida and Washington, D.C. did not provide data.

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

21

State and County Landscape

FIGURE 3

Marijuana Possession Arrest Rate per 100k

People (2010–2018)

Since most drug law enforcement occurs at the state

and local level, it is crucial that an examination of

marijuana possession arrests focus on state and

county data.

400

300

200

States

100

0

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data and U.S. Census Data

Note: Florida and Washington, D.C. did not provide data.

FIGURE 4

Number of Arrests by Drug Type (2000–2016)

1,000,000

Marijuana

750,000

Opium and Cocaine

500,000

250,000

Synthetic Narcotics

0

2000

2005

2010

2015

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data

Note: This graph excludes data from New York City, Illinois, Florida, and Washington,

D.C., which were not available at time of this analysis.

TABLE 1

National Arrests for Marijuana and All Drugs

Year

Total

Marijuana

Arrests

All Drug

Arrests

% All Drug

Arrests That

Were for

Marijuana

2010

831,849

1,556,916

53.4%

2011

768,390

1,488,628

51.6%

2012

734,019

1,469,273

50.0%

2013

856,263

1,702,249

50.3%

2014

679,188

1,453,543

46.7%

2015

595,127

1,369,543

43.5%

2016

611,026

1,445,215

42.3%

2017

702,778

1,613,926

43.5%

2018

692,965

1,603,316

43.2%

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data

22

ACLU Research Report

Not surprisingly, arrest rates vary greatly between

states. Here, we provide a comparative assessment;

specific profile sheets for every state are available in

the State Profiles section of this report.43

The national marijuana possession arrest rate in

2018 was 203.88 per 100,000. State arrest rates

ranged from 707.34 arrests per 100,000, in South

Dakota, to 4.52 arrests per 100,000 people, in

Massachusetts (see Appendix, Table A for data for all

states). Not only did South Dakota have the highest

arrest rate in 2018 (see Figure 5), it also had the

greatest growth, with a 176% increase in marijuana

possession arrests from 2010. Although nationally

there was a decline in marijuana possession arrests,

arrest rates actually increased in 17 states (see Table

2).

In terms of total raw numbers of arrests, Texas had

the highest total number of marijuana possession

arrests, with an estimated 70,017 arrests in the year

2018 alone (see Appendix, Table B). In 12 states,

marijuana arrests accounted for more than half

of all drug arrests in 2018, with Wyoming having

the highest percent of all drug arrests that were

for marijuana possession, at 58.6% (see Appendix,

Table B for total number of all drug arrests and total

number of marijuana possession arrests by state).

Counties

Not only do states vary widely in marijuana

enforcement, but even within states there remains

a range in how marijuana offenses are treated at

the county level. Individual district attorneys and

police departments have a substantial amount of

discretion in deciding who gets arrested, charged,

FIGURE 5

States With Highest Marijuana Possession Arrest Rates per 100k (2018)

South Dakota

South Carolina

Wyoming

West Virginia

Georgia

Louisiana

Nebraska

New Jersey

Tennessee

Utah

Missouri

North Dakota

Idaho

Wisconsin

Arkansas

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data and U.S. Census Data

and convicted for drug possession. In some cases,

municipalities have passed their own ordinances

related to marijuana use and enforcement.

Table 3 lists the 20 counties with the highest

marijuana possession arrest rates in 2018. Four

of the top five counties are in South Carolina, the

state with the second highest arrest rates for

marijuana possession. Less predictably, three

Maryland counties are represented in the top 10,

even though Maryland decriminalized certain

amounts of possession in 2014. Although these

counties had the highest arrest rates in 2018,

other counties have had greater increases in

their rates over time, such as Prince George and

Charlottesville City in Virginia and Lawrence,

Alabama. See Table 4 for a list of the 20 counties

with the greatest increases since 2010.

States That Legalized or

Decriminalized Marijuana

Possession

Since our last report in 2013, several states have

legalized or decriminalized marijuana offenses.

Although these laws vary in their specific elements

and implementation, we examine if — and how

TABLE 2

States With Increases in Marijuana Possession

Arrest Rates (2010–2018)

Arrest Rates per 100k

State

% Change

Total Arrest Total Arrest in Total

Rate (2010) Rate (2018) Arrest Rate

South Dakota

256.17

707.34

176.1%

Utah

150.64

343.37

127.9%

North Dakota

180.64

332.52

84.1%

Wyoming

384.56

592.89

54.2%

South Carolina

440.57

673.26

52.8%

Arkansas

215.85

322.12

49.2%

West Virginia

299.85

447.32

49.2%

Idaho

225.02

332.16

47.6%

New Jersey

253.75

369.54

45.6%

Ohio

184.03

248.68

35.1%

New Mexico

168.15

225.71

34.2%

Virginia

236.12

314.33

33.1%

Pennsylvania

180.45

226.52

25.5%

Tennessee

283.50

343.94

21.3%

Georgia

361.87

428.81

18.5%

Louisiana

349.32

412.48

18.1%

Wisconsin

289.37

324.37

12.1%

Source: FBI/Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data and U.S. Census Data

A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform

23

— these laws have affected arrest rates and, in a

subsequent section, racial disparities in arrests.

As of March 2020, 11 states and Washington,

D.C. had legalized marijuana possession and an

additional 15 states had decriminalized marijuana

possession (see Appendix, Table C). At the time

of this report, however, the most current data

available was from 2018, and thus, for the following

analyses, we considered only states that legalized or

decriminalized before 2018. See Table 5 for the listing

of such states.44 We also provide a full listing of the

legal status of marijuana possession for all states and

D.C. as of March 2020 in the Appendix (Table C).

Legalized States

In 2018, on average, legalized states had the lowest

arrest rates for marijuana possession compared

to other states.45 Although legalized states also

had lower rates of possession arrests even before

legalization, the over-time trends make it clear that

legalization has made a difference overall. Figure

TABLE 3

TABLE 4

Top 20 Counties for Marijuana Possession

Arrest Rates per 100k people (2018)

Top 20 Counties for Largest Increases in

Marijuana Possession Arrest Rates per 100k

people (2010-2018)

Possession

Arrest Rates

County

County

2010

Rate

2018

Rate

%

Increase