Dp Info Ctr Death Penalty 2012 Year End Report

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

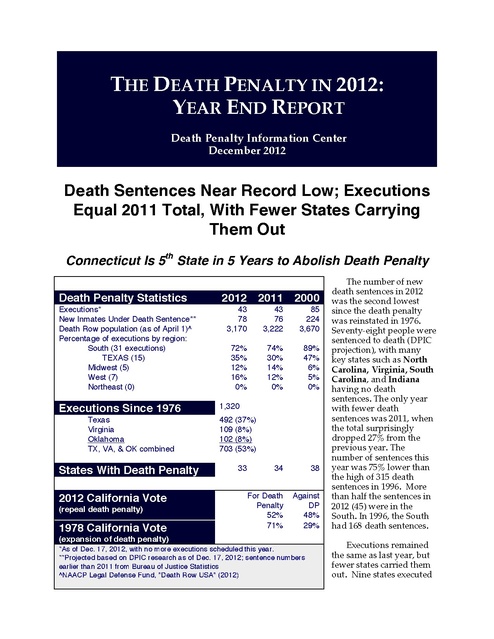

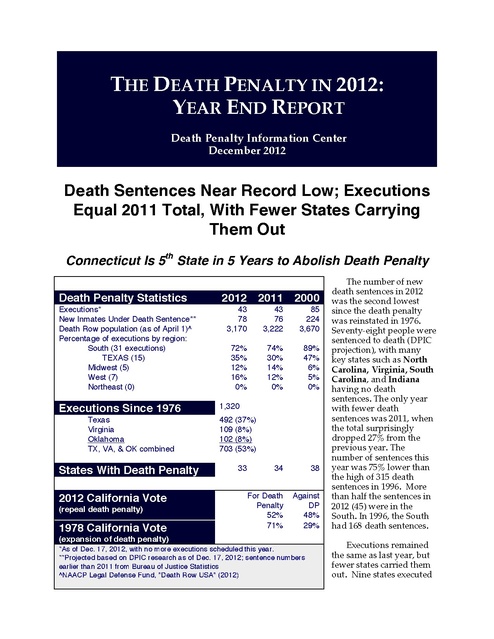

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2012: YEAR END REPORT Death Penalty Information Center December 2012 Death Sentences Near Record Low; Executions Equal 2011 Total, With Fewer States Carrying Them Out Connecticut Is 5th State in 5 Years to Abolish Death Penalty Death Penalty Statistics Executions* New Inmates Under Death Sentence** Death Row population (as of April 1)^ Percentage of executions by region: South (31 executions) TEXAS (15) Midwest (5) West (7) Northeast (0) Executions Since 1976 Texas Virginia Oklahoma TX, VA, & OK combined States With Death Penalty 2012 California Vote (repeal death penalty) 1978 California Vote 2012 2011 2000 43 78 3,170 43 76 3,222 85 224 3,670 72% 35% 12% 16% 0% 74% 30% 14% 12% 0% 89% 47% 6% 5% 0% 34 38 For Death Penalty 52% 71% Against DP 48% 29% 1,320 492 (37%) 109 (8%) 102 (8%) 703 (53%) 33 (expansion of death penalty) *As of Dec. 17, 2012, with no more executions scheduled this year. **Projected based on DPIC research as of Dec. 17, 2012; sentence numbers earlier than 2011 from Bureau of Justice Statistics ^NAACP Legal Defense Fund, "Death Row USA" (2012) The number of new death sentences in 2012 was the second lowest since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. Seventy-eight people were sentenced to death (DPIC projection), with many key states such as North Carolina, Virginia, South Carolina, and Indiana having no death sentences. The only year with fewer death sentences was 2011, when the total surprisingly dropped 27% from the previous year. The number of sentences this year was 75% lower than the high of 315 death sentences in 1996. More than half the sentences in 2012 (45) were in the South. In 1996, the South had 168 death sentences. Executions remained the same as last year, but fewer states carried them out. Nine states executed Year End Report 2012 p. 2 Executions by State Texas Arizona Oklahoma Mississippi Ohio Florida South Dakota Delaware Idaho Alabama Georgia Virginia South Carolina Missouri TOTALS 2012 2011 15 6 6 6 3 3 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 43 13 4 2 2 5 2 0 1 1 6 4 1 1 1 43 inmates in 2012—compared to 13 in 2011—equaling the fewest number of states to do so in 20 years. Just 4 states (Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Arizona) were responsible for over three-quarters of the executions in the U.S. Fewer Death Penalty States Connecticut became the fifth state in five years to abolish the death penalty. The legislation was passed after vigorous debate and with the support of many families of murder victims. Eleven inmates remained on death row since the law was not retroactive, though challenges to their sentences continue. The other four states that ended the death penalty recently are New Jersey, New York, New Mexico, and Illinois. In signing the repeal bill in April, Governor Dannel Malloy noted the role of victims’ families, "[T]he campaign to abolish the death penalty in Connecticut has been led by dozens of family members of murder victims, and some of them were present as signed this legislation today. In the words of one such survivor: ‘Now is the time to start the process of healing....'" I California Referendum California came close to following Connecticut in a November referendum in which almost half the electorate (48%) supported the total abolition of capital punishment in the state. This was a dramatic shift from the 29% of the public who voted against expanding the death penalty in 1978. Some of those who led the effort to end the death penalty were former supporters of the law and many came from law enforcement backgrounds, such as Gil Garcetti, former District Attorney of Los Angeles, Jeanne Woodford, former warden of San Quentin prison, George Gascon, former police chief and current District Attorney of San Francisco, and Darryl Stallworth, former Deputy District Attorney of Alameda County. Garcetti captured much of the frustration with California’s dysfunctional system: "Much like millions of other voters, I changed my mind on the death penalty when I understood that it serves no useful purpose, that spending $184 million annually on it is obscenely expensive, and that some of California's condemned are likely to be innocent." California has not carried out an execution in almost 7 years. It is not clear when executions will resume, as challenges to lethal injection and the fairness of the death penalty remain. Polls showed a growing awareness among voters of the high cost of capital punishment—amounting to $4 billion since its reinstatement there in 1977. Executions Thirty-six percent fewer states carried out executions in 2012 than in 2011. More than half the states (29) in the country either do not have the death penalty or have not carried out an execution in five years, and almost half (23) have been without executions in ten years. All executions in 2012 were by lethal injection, and all used a relatively new drug, pentobarbital, either alone or in combination with other drugs. Only 16% of the executions this year stemmed Year End Report 2012 p. 3 from the murder of a black victim, even though blacks are the victims in about 50% of murders in the U.S. A study released this year in Connecticut, which abolished the death penalty, by Professor John Donohue of Stanford University found that minority defendants whose victims were white were three times more likely to receive a death sentence than white defendants whose victims were white. One common theme running through the histories of many of those facing execution this year was the presence of severe mental illness. The Supreme Court has banned the execution of those with intellectual disabilities (mental retardation) and those with no rational understanding of their punishment (insanity). However, there is no exclusion for people with diagnoses such as schizophrenia, acute paranoia, or bi-polar disorder. Lower courts feel hampered by the lack of precedent in this area, many governors are hesitant to grant clemency, and state legislatures have yet to address this issue. At least ten of those executed or scheduled to be executed this year showed signs of severe mental illness. In Tibbals v. Carter the Supreme Court will decide the narrow question of whether appeal deadlines should be extended if an inmate is too mentally incompetent to assist his attorneys. However, the larger question of whether some defendants should be automatically excluded from the death penalty because of their severe mental illness at the time of their crime remains unresolved. Some inmates with severe mental illness received stays of execution in 2012, including John Ferguson in Florida, Marcus Druery in Texas, and Abdul Awkal in Ohio. Others, however, with compelling histories of mental illness were executed: • Garry Allen was executed in Oklahoma on November 6 despite a diagnosis of schizophrenia and dementia caused by seizures, drug abuse, and a gunshot wound to his head. The Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board had recommended a commutation, but DEATH ROW INMATES BY Year End Report 2012 p. 4 STATE (April 1, 2012) California 724 Florida 407 Texas 308 Pennsylvania 204 Alabama 200 N. Carolina 165 Ohio 150 Arizona 132 Georgia 100 Louisiana 90 Tennessee 88 Nevada 80 Oklahoma 66 U. S. Government 60 S. Carolina 56 Mississippi 53 Missouri 47 Arkansas 40 Oregon 37 Kentucky 35 Delaware 18 Idaho 14 Indiana 14 Virginia 12 Nebraska 11 Connecticut* 11 Kansas 10 Utah 9 Washington 9 U.S. Military 6 Maryland 5 South Dakota 5 Colorado 4 Montana 2 New Mexico* 2 New Hampshire 1 Wyoming 1 Total death row 3,170 Six inmates in the national total received two death sentences in different states *Abolished death penalty for future cases Governor Mary Fallin denied clemency. Allen murdered his wife 26 years ago, after she had left him and taken their two children. • Arizona executed Robert Moormann on February 29. His attorneys said he killed and dismembered his adoptive mother after years of sexual abuse. At his trial, a defense psychologist testified that Moormann suffered from organic delusional syndrome, pedophilia, and schizoid personality disorder, and was unable to appreciate the nature and consequences of his actions. Moormann was born to a 15-year-old girl who drank heavily, engaged in prostitution, and died at age 17. In school he showed evidence of mental retardation and attended special education classes. He was first committed to a mental institution when he was 13. • Edwin Turner was executed in Mississippi on February 8. Turner had a long family history of mental illness: his greatgrandmother and grandmother were committed to state hospitals; Turner’s mother attempted suicide twice; and his father was killed in an explosion that some believe was a suicide. Turner had also attempted suicide several times, including one instance at age 18 that left his face permanently disfigured. His attorneys argued that he was mentally unbalanced at the time of his crime and continued to be so at his execution. At least 38 scheduled executions were stayed in 2012, including 3 stays issued by the U.S. Supreme Court. Four inmates were granted clemency this year, one each in Delaware (defendant suffered severe childhood abuse) and Georgia (life without parole not available as a sentencing option when defendant was sentenced), and 2 in Ohio (one defendant’s limited mental capacity; one, inadequate representation). Pennsylvania prepared to carry out its first non-consensual execution in 50 years with the lethal injection of Terrance Williams (pictured, at age 17). However, significant evidence emerged that Williams, who had just turned 18 at the time of his crime, had been sexually abused by the man he killed-information improperly withheld from his attorneys. A Pennsylvania judge stayed the execution, granting him a new sentencing hearing, though that ruling is being challenged. Death Sentences Death sentences are predictors of the future of the death penalty in the U.S. The number of sentences has steadily declined since 1998. Last year, there were fewer than 100 death sentences, for the first time since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. This year, the number remained well below 100. If two cases to be finally adjudicated by the end of the year result in death sentences, the number of new sentences is projected to be 78, a slight increase Year End Report 2012 p. 5 from last year’s total of 76, but still 25% less than 2010 and 65% less than 2000. In the future, fewer death sentences will mean fewer executions as well. Death Sentences 1977 -‐ 2012 350 Death Sentences 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Years For the eighth consecutive year, Texas executed more people than it sentenced to death, foreshadowing a decline in executions in the future. There were no death sentences in Houston, which used to be referred to as the “capital of capital punishment.” Prominent death penalty states in the South, including North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia (which has been second to Texas in executions) remarkably had no death sentences and no executions in 2012. Georgia had two death sentences and no executions; Louisiana had one sentence and no executions. Death sentences, like executions, were largely clustered in a few states. Just four states (Florida (21), California (14), Texas (9), and Pennsylvania (7)) accounted for 65% of the country’s death sentences. Within states the use of the death penalty is often concentrated in only a few counties. This substantial financial burden is generated by a small minority but borne by all the taxpayers. Innocence In September, Damon Thibodeaux was freed from death row in Louisiana after an extensive investigation, including DNA testing, with the cooperation of Jefferson Parrish District Attorney Paul Connick. Thibodeaux at first confessed to killing his cousin after a nine-hour interrogation but recanted a few hours later, saying his confession was coerced. Thibodeaux became the 141st person to be exonerated and freed from death row since 1973, and the 18th person released through DNA evidence. Attorney Barry Scheck of New York’s Innocence Year End Report 2012 p. 6 Project noted, “People have a very hard time with the concept that an innocent person could confess to a crime that they didn’t commit. But it happens a lot. It’s the ultimate risk that an innocent man could be executed." Missouri convened a special hearing to review the case of Reggie Clemons, who has been on death row for 19 years. Clemons' conviction was based partly on his confession to rape, which he said was beaten out of him by the police. Because of doubts about the validity of his conviction, a special master was appointed to determine whether the prosecution committed misconduct; a report will be made to the state’s Supreme Court in 2013. In Texas, the family of Cameron Willingham has petitioned the Board of Pardons and Paroles to grant him a posthumous pardon based on new evidence that has emerged since his execution in 2004. Willingham was sentenced to death for the murder of his three children in a house fire in 1991. At his trial, investigators testified that Willingham had intentionally set the fire, but the basis for that conclusion has since been completely discredited. Experts now believe the fire was accidental. The other evidence presented at Willingham's trial included the testimony of a jailhouse informant who later recanted his assertion that Willingham admitted to the crime. A comprehensive investigation by Prof. James Liebman of Columbia University, published in the Human Rights Law Review, of another Texas execution concluded Carlos DeLuna was innocent and had been wrongly convicted on the basis of unreliable testimony. Strong evidence pointed to a man named Carlos Hernandez, who looked like DeLuna and had bragged about the murder. Hernandez had a history of violent crimes, including ones similar to the crime for which DeLuna was executed. Liebman wrote that DeLuna was convicted "on the thinnest of evidence: a single, nighttime, cross-ethnic eyewitness identification and no corroborating forensics." Deterrence Research A report released in April by the National Research Council, associated with the National Academy of Sciences, concluded studies conducted over the past 35 years claiming a deterrent effect from the death penalty are “fundamentally flawed,” “should not be used to inform deliberations requiring judgments about the effect of the death penalty on homicide,” and “should not influence policy judgments about capital punishment.” Professor John Donohue of Stanford Law School and a research associate for the National Bureau of Economic Research said such past unreliable studies “have now been properly interred.” (The report is available from The National Academies Press, www.nap.edu.) Contrary to the predictions of some death penalty proponents, the murder rate in the U.S. has declined even as the death penalty is being used less. In October, the FBI released its annual Uniform Crime Report for 2011, showing another drop in the country’s murder rate. Since 2000, when the murder rate was 5.5 murders per 100,000 people, the rate has declined about 15% to 4.7. The lowest murder rate among the four geographical regions was in the Northeast, which uses the death penalty the least; it also had the largest decrease in its murder rate from the previous year. The highest rate was in the South, which executes the most people. Public Opinion According to the 2012 American Values Survey conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, Americans are now evenly divided on whether the death penalty or life without parole Year End Report 2012 p. 7 is the appropriate punishment for murder. The survey, released shortly before the elections, found that 47% of respondents favored life without parole, while 46% favored the death penalty. Life without parole was favored by African-Americans (64%), Hispanic-Americans (56%), women (52%) and millennials (ages 18 to 29) (55%). Support for the death penalty was strong among Republicans (59%), Tea Party members (61%), and white Americans (53%). In one demographic, views on the death penalty differed from those on other social issues: nonCatholic conservatives favored the death penalty by almost 20 percentage points (56-37%), but Catholic conservatives supported life without parole (51-44%). New Voices Each year new voices, including leaders in law enforcement and former supporters of the death penalty, speak out against the death penalty. Below are some of the voices heard this year: George Gascon served for 30 years as a police officer, including as a police chief in Arizona and California, and currently is the District Attorney of San Francisco. Although he formerly supported the death penalty, Gascon now believes it should be replaced with life without parole: “I have had the opportunity to observe and participate in the development and implementation of public safety policies at every level. I have seen what works and what does not in making communities safe. Given my experience, I believe there are three compelling reasons why the death penalty should be replaced. (1) The criminal justice system makes mistakes and the possibility of executing innocent people is both inherently wrong and morally reprehensible; (2) My personal experience and crime data show the death penalty does not reduce crime; and (3) The death penalty wastes precious resources that could be best used to fight crime and solve thousands of unsolved homicides languishing in filing cabinets in understaffed police departments across the state.” Editorial: “For most of its 162 years as a state, California has had laws on the books authorizing the death penalty. And for nearly all of its 155 years as a newspaper, The Bee has lent its support to those laws and use of capital punishment to deter violence and punish those convicted of the most horrible of crimes. That changes today. The death penalty in California has become an illusion, and we need to end the fiction – the sooner the better. The state's death penalty is an outdated, flawed and expensive system of punishment that needs to be replaced with a rocksolid sentence of life imprisonment with no chance of parole.” Justice Lubbie Harper, Jr., of Connecticut’s Supreme Court came to the conclusion that the state’s death penalty has been applied unconstitutionally. “It is clear to me both that capital punishment violates our state’s constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment and that this punishment is systematically plagued by an unacceptable risk of arbitrary and racially discriminatory imposition that undermines the fairness and integrity of Connecticut’s criminal justice system as a whole.” Jim Petro, a former Attorney General of Ohio, strongly supported the death penalty as a state legislator, believing it was a deterrent and Ohio would save money using it. However, he recently concluded, "Neither of those things have occurred, so I ask myself, 'Why would I vote for it again?' I don't think I would. I don't think the law has done anything to benefit society and us. It's cheaper and, in my view, sometimes a mistake can be made, so perhaps we are better off with life without parole." Year End Report 2012 p. 8 Conclusion Use of the death penalty in 2012 continued to decline, with fewer states endorsing capital punishment, relatively few death sentences being imposed, and executions being carried out at only half the rate of the late 1990s. Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina--traditional death penalty states--had no death sentences or executions this year. Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana had no executions. The projected number of death sentences this year is 78, slightly higher than in 2011, but sharply lower than any other year since 1976. Only 9 states carried out an execution, indicating the isolation of this practice. Even in Texas, death sentences over the past few years have been at a historic low. Five states have abolished the death penalty in the past five years. Connecticut became the latest state to join 16 other non-death penalty states. Although voters in California narrowly chose to continue the death penalty, support there is much lower than it was 35 years ago. Other states, like Maryland, Colorado, and New Hampshire, appear to be moving closer to legislative votes like Connecticut’s. I cannot stand the thought of being responsible for someone being falsely accused and facing the death penalty. For me this is a moral issue...I don't want to be part of a system that sends innocent people…to the death penalty. -Sen. Edith Prague (voting to abolish Connecticut’s death penalty) When a law is so rarely imposed, and the rationale for its imposition discredited, its continued use is placed in doubt. Many criminal justice experts have changed their position and no longer support the death penalty. The remnant of the punishment that continues often falls on mentally ill defendants and those sentenced many years ago pursuant to practices no longer commensurate with current legal standards. In a time of grave fiscal concerns, the high cost of the death penalty is providing an additional rationale for its reconsideration. Based on these trends, the death penalty appears to be an increasingly irrelevant component of our criminal justice system. Death Penalty Information Center Washington, D.C. (202) 289-2275 dpic@deathpenaltyinfo.org www.deathpenaltyinfo.org The Death Penalty Information Center is a non-profit organization serving the media and the public by providing information and analysis on capital punishment. The Center provides in-depth reports, conducts briefings for journalists, promotes informed discussion, and serves as a resource to those working on this issue. Richard Dieter, DPIC’s Executive Director, wrote this report with assistance from DPIC staff. Further sources for facts and quotations in it are available upon request. The Center is funded through the generosity of individual donors and foundations, including the Roderick MacArthur Foundation and the Open Society Foundations. The views expressed in this report are those of DPIC and should not be taken to reflect the opinions of its donors.