Growing Up Locked Down - Juvenile Solitary Confinement in NE, ACLU 2016

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

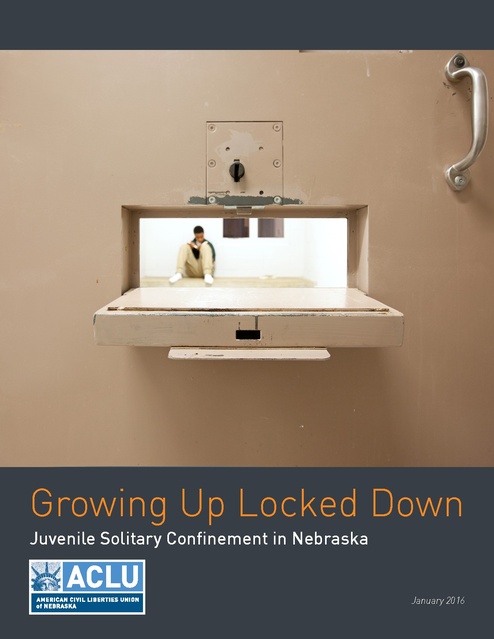

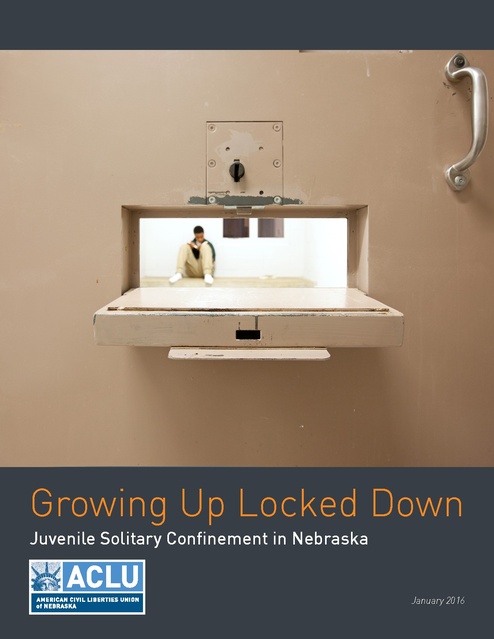

Growing Up Locked Down Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska January 2016 Growing Up Locked Down Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU OF NEBRASKA STAFF BOARD OF DIRECTORS Danielle Conrad Executive Director Gloria Romero-Downing (President) Leslie J. Seymore (National Board Representative) Christy Abraham (First Vice President) Linda Pratt (Second Vice President) Ashley Moffat (Secretary) Laurie Thomas Lee (Treasurer) Dwayne Ball Jim Bender Joan Birnie Tiffany Crouse James Dake Eileen Durgin-Clinchard Brenda Ealey Shelton Hendricks Rich Juro Nicholas Mirkay Peter Levitov Luis Sotelo Amy Miller Legal Director Tyler Richard Communications Director Maria Funk Director of Administration and Finance Christopher “Spike” Eickholt Government Liaison INTRODUCTION The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, nonpartisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual freedoms and civil liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. We serve over 2,000 members and supporters throughout our great state and represent more than 500,000 members nationwide. The ACLU is committed to protecting the constitutional rights of juveniles in detention. The use of solitary confinement violates juveniles’ rights under the following theories: §§ §§ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS §§ Photos cover, page 8, page 13: © Richard Ross www.juvenile-in-justice.com §§ Photos page 5, page 22: Phil Jarret, www.cleverchap.com Theresa Cusic, Law Clerk: University of Nebraska College of Law '17 conducted the research and data compilation that formed the bulk of this report. §§ §§ US Constitution 8th Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment US Constitution 5th Amendment guarantee of due process US Constitution 14th Amendment guarantee of due process Nebraska State Constitution Article I-9 prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment Nebraska State Constitution Article I-3 guarantee of due process Americans with Disabilities Act On any given day in Nebraska, juvenile justice facilities routinely subject kids in their care to solitary confinement. The solitary confinement of children is suspect from a legal and policy perspective. Solitary confinement can cause extreme psychological, physical, and developmental harm. For adults, the effects can be persistent mental health problems, or worse, suicide. And for children, who are still developing and more vulnerable to irreparable harm, the risks of solitary are magnified – protracted isolation and solitary confinement can be permanently damaging, especially for those with mental illness. It is time to scrutinize the use of solitary confinement on children. Nebraska should strictly limit and uniformly regulate isolation practices to ensure our state comports with best practices that provide positive outcomes for vulnerable youth and to ensure Nebraska quickly remedies potential systemic legal issues. Amy Miller, Legal Director: Amy is a graduate of Grinnell College and the University of Nebraska College of Law. Since 1999, Amy has guided the legal work of the ACLU. She is a frequent lecturer on civil rights and liberties for the Nebraska Bar Association, law schools and general audiences. This report and related research was made possible through the generous support of the Cooper Foundation. 2 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU of Nebraska | 3 Dylan Dylan spent 10 to 12 hours locked away from other youth when he was 14 and in an Omaha psychiatric facility. He had admitted that he felt suicidal or self harming. In response, his facility put him in “the quiet room.” “ It was set up to be the definition of insanity. Just the four white walls, the camera, the mattress. It was horrible. It felt horrible. It was more anxiety-producing because you’re not talking to anyone. If you can’t be lucky enough to fall asleep then you have nothing and it’s just waiting for the human being to come back to the door. It’s so upsetting, you’re alone with your thoughts. No one to talk it out with. Not even a window to look out of. In order to avoid being put back into the quiet room, Dylan lost all trust in the system and changed his future interaction with staff: “ So I learned to never say anything real after that to keep them happy. Even when I did feel terrible and wished I could talk about my depression or suicidal thoughts, I stayed silent. 4 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska REPORT OVERVIEW Before they are old enough to get a driver’s license, enlist in the armed forces, or vote, some children in Nebraska are held in solitary confinement for days, weeks—and even months. This practice occurs in every Nebraska juvenile justice facility, to varying degrees, but the overarching theme of overuse is consistent throughout the state. On any given day in Nebraska, juvenile justice facilities routinely subject the kids in their care to solitary confinement. Like adult prisons, juvenile facilities sometimes employ the most counterproductive and inhumane correctional practices—including extended periods of solitary confinement, room restriction, isolation, segregation, and seclusion. Isolation practices frequently involve placing a youth alone in a cell for several hours, sometimes for multiple days; restricting contact with family members; limiting access to reading and writing materials; and providing limited educational programming, recreation, drug treatment, or mental health services. Throughout this report, “solitary confinement” refers to any physical and social isolation of children in juvenile detention facilities. It does not refer to short intervention “time out” practices used to help a juvenile manage current acting out behavior. While temporary use of seclusion for a youth may be necessary to maintain the safety and security of that youth or other people, the use of solitary confinement on children in Nebraska is clearly overused, and can cause much more serious problems than those it is supposedly employed to solve. Additionally, our research has uncovered that frequently the reasons why young people are placed in solitary confinement can be for even relatively minor offenses, such as talking back to staff members, having too many books, or refusing to follow directions. This research gives rise to the concern that juvenile facilities in Nebraska are not utilizing best practices for the use of solitary confinement and 6 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska thus are risking serious mental health impacts for vulnerable youth. The ACLU of Nebraska generated the idea for this research in concert with a growing national conversation about the very specific harms of solitary confinement on juvenile brain development. Mental health professionals have established that the negative psychological impacts of solitary on the adult brain are greatly magnified on the developing juvenile brain and can lead to permanent damage. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatrists oppose the use of solitary confinement for juveniles.1 Experts at the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative recommend a juvenile be placed in solitary for no longer than four hours.2 Our partners at Voices for Children recently completed a multi-year study of the two youth centers run by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) at Geneva and Kearney.3 Their findings show these facilities are making some progress to decrease the average stay in solitary confinement but both facilities are still far in excess of best practices. For example, some facilities are holding children up to five days in restricted settings without peer contact, as described later in this report. While vitally important, this research of state facilities does not tell the full story of youth solitary confinement in Nebraska since it was limited to only the two DHHS-operated facilities. In 2015 the ACLU of Nebraska decided to conduct more comprehensive statewide research regarding all of the remaining juvenile detention centers in Nebraska to determine what, if any, their written policies are and their actual practices in regards to the use of solitary confinement. There are two other state facilities—the Nebraska Department of Corrections houses young male offenders at the Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility and houses young ACLU of Nebraska | 7 female offenders at the York Correctional Center for Women. There are also five county facilities located in Douglas County, Lancaster County, Sarpy County, Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services in Norfolk, and Scotts Bluff County. The results of our research demonstrates that these facilities are using solitary far more frequently and for far longer periods than their DHHS counterparts and far in excess of best practices. This report explains how solitary confinement harms children, catalogs solitary confinement policies used by Nebraska’s juvenile detention facilities, and outlines a path to reform that would decrease the use of solitary confinement in juvenile detention centers because we can and we must do better for our vulnerable youth in Nebraska. EXISTING NEBRASKA LANDSCAPE Nebraska far exceeds the national average for the number of youth residing in juvenile detention, correction, or residential facilities. In fact, Nebraska has the third highest per capita number of youth in juvenile facilities as ranked by the Annie E. Casey Kids Count Data Center.4 Additionally, our research reveals that Nebraska is also an outlier in terms of policies that permit lengthy periods of solitary confinement, with one shocking example of a policy allowing for the use of solitary for up to 90 days. Even more disturbing, some facilities surveyed have no policies governing solitary confinement or data to track usage of solitary confinement. As described below, most of Nebraska’s neighboring states restrict the use of solitary for youth along a range of 24 hours to 5 days. Approximately 8,000 juvenile cases are reported to the Nebraska Crime Commission each year.5 Thus, reform in this area is critical to improving the quality of life for the hundreds of vulnerable Nebraska children in detention facilities within the juvenile justice system.6 It is also important to note that the juvenile justice system has disproportionate impacts among communities of color: 55% of juveniles in detention in our state are children of color.7 Many young Nebraskans who are presently detained are not public safety threats and could potentially be rehabilitated through much less restrictive means or at the very least should not be subjected to mental anguish during their period of detention. These conditions of confinement can have long lasting effects on their ability to successfully transition back into their families, our communities, and the economy. RACIAL DISPARITIES IN NEBRASKA JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITIES 4 in 20 youth in Nebraska are youth of color. 11 in 20 youth in Nebraska Juvenile Facilities are youth of color. Source: Kids Count Data Center 8 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU of Nebraska | 9 THE OVERUSE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT HARMS NEBRASKA CHILDREN The overuse of solitary confinement for children is highly suspect from both a legal and policy perspective. Solitary confinement can cause extreme psychological, physical, and developmental harm. For adults, the effects can be persistent mental health problems and even result in suicide. Children are more vulnerable as they are still developing physically and mentally-thus, the risks and impacts of solitary are magnified and more pronounced – particularly for kids with disabilities or kids with histories of trauma and abuse. The research cited below draws heavily from two national ACLU reports on juvenile solitary confinement: “Growing Up Locked Down: Youth in Solitary Confinement in Jails and Prisons Across the United States” (2012) and “Alone and Afraid: Children Held in Solitary Confinement” (2014). §§ Psychological Damage Mental health experts agree that long term solitary confinement is psychologically harmful for adults – especially those with pre-existing mental illness.8 The effects on children are even more severe due to their unique developmental needs. 9 §§ Increased Suicide Rates A tragic consequence of the solitary confinement of youth is the increased risk of suicide and self-harm, including cutting and other acts of self-mutilation. According to research published by the Department of Justice, more than 50% of all youth suicides in juvenile facilities occurred while young people were isolated alone in their rooms, and more than 60% of young people who committed suicide in custody had a history of being held in isolation.10 §§ Denial of Education and Rehabilitation Access to regular meaningful exercise, to reading and writing materials, and to adequate mental health care – the very activities that could help troubled youth grow into healthy and productive citizens – is hampered when youth are confined in isolation.11 Failure to provide appropriate programming for youth inhibits their ability to grow and develop normally, to access legal services, and to contribute to society upon their release.12 §§ Stunted Development Young people’s brains and bodies are developing, placing youth at risk of physical and psychological harm when healthy development is impeded.13 The evidence is undisputed that youth require regular exercise and activity to support growing muscles and bones.14 Additionally, since many children in the juvenile justice system have disabilities or histories of trauma and abuse, solitary confinement can be even more harmful to the child’s future ability to lead a productive life.15 10 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Lisa was placed in solitary confinement in an Omaha psychiatric facility after threatening self-harm at age 14. “ The room had mesh over the window so you couldn’t look outside. It was an empty room with a cement floor, just plain white walls. There was no mat, nothing in there with you, the room was totally stripped bare. When they closed the steel door, I’d hold onto the door jamb, trying to make it impossible for them to shut me in. Ironically (because I was in solitary for self harm), I survived my time alone by just falling back on hurting myself. I’d bite my own cheeks and tongue, banging my head on the wall. Lisa is now a psychologist and mother. She works with young people with behavioral health problems, motivated in part by her desire to ensure no juvenile goes through what she did. “ Being locked down alone just reinforced the unhealthy beliefs I already had so I heard “You’re a freak, you don’t belong in the world and you don’t belong around other people.” What are the facilities trying to accomplish? If it is to manage somebody’s behavior so they don’t harm themselves or someone else, it doesn’t work—it just creates more isolation, anger and separation and hopelessness. We need to be cognizant of how many traumatic and difficult, violating experiences these youths have already had. Solitary just re-traumatizes them. Much of what was done to me was out of ignorance, not evil, but I want people to recognize that we can change things for the better. Lisa CONSTITUTIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LAW PROVIDE SPECIAL PROTECTIONS FOR CHILDREN Recent Supreme Court jurisprudence makes clear that youth and adults must be treated differently in the context of crime and punishment. For example, we no longer permit juveniles to be given the death penalty nor life without parole.16 As the United States Supreme Court wrote in abolishing life without parole for juveniles, “…developments in psychology and brain science continue to show fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds.”17 In addition to these Supreme Court opinions on the difference between youth and adults, there is a growing trend among lower courts in cases specifically regarding juveniles in solitary confinement. For instance, two young men who experienced mental health deterioration while held in solitary confinement in juvenile facilities in New Jersey prevailed against the state in a $400,000 settlement.18 Similar lawsuits have been filed with successful resolutions in Illinois, New York and Ohio.19 International human rights law also distinguishes between youth and adults, mandating that youth who commit crimes receive rehabilitative punishments appropriate to their age and status.20 According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, solitary confinement of youth is cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment and in some cases, torture.21 The ACLU’s research in Nebraska shows that Nebraska facilities fail to comply with constitutional and human rights law. RESEARCH IN NEBRASKA In order to fully evaluate the policies and use of solitary confinement in Nebraska youth detention facilities the ACLU began by identifying current written policies from each facility. Next, the ACLU conduced an open records request, asking each facility to provide logs showing length of stay and frequency of use of solitary for an 18-month period, covering January 2014 through June 2015 in order to evaluate implementation of the policies and actual use of solitary confinement. The findings of this research are outlined in the following pages. It is important to note at the outset that the Douglas County Youth Center and Scotts Bluff County Detention Center responded to our requests and indicated that they do not even keep time logs which would permit us to calculate the usage rates. This disappointing lack of data in two major youth facilities raises concerns and demonstrates a clear need for meaningful statewide reforms. Experts do not distinguish between “room restriction” where a juvenile is confined alone in their cell and “solitary confinement” in a special locked unit—the mental health impacts are the same. Our requests from the facilities encompassed all forms of isolation from peers. Some facilities reported they use room restriction for periods, then permit the juvenile to attend classes before placing the juvenile back in room restriction. In contrast, some facilities impose room restriction or solitary confinement without any periods out of isolation. The data below incorporates all isolation as reported by the facilities without differentiation. ACLU of Nebraska | 13 INVENTORY OF NEBRASKA JUVENILE DETENTION FACILITIES & SOLITARY CONFINEMENT POLICIES Nebraska currently has nine juvenile detention centers. Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center - Kearney Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center - Geneva Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility and Nebraska Correctional Center for Women22 Two state youth centers run by the Department of Health and Human Services 1 Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center at Kearney - males 2 Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center at Geneva - females Douglas County Youth Center Two state facilities run by the Nebraska Department of Corrections 3 Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility - males 4 Nebraska Correctional Center for Women - females Lancastser County Youth Services Five county facilities 5 Douglas County Youth Center 6 Lancaster County Youth Services 7 Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services Center (Norfolk) 8 Sarpy County Juvenile Justice Center 9 Scotts Bluff County Detention Center As evidenced in the policy inventory below it is apparent that young people are held in solitary confinement as a form of punishment for major and minor rule violations; they are held in solitary as a safety precaution to protect them from adult inmates; they are held in solitary to promote prison management; and sometimes, they are held in solitary for medical purposes. The myriad of ways a young person can be placed in solitary is accompanied by time limit variations that reflect facility-unique policies. Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services Center (Norfolk) These policies demonstrate a disturbing lack of uniformity at each of Nebraska’s juvenile detention centers. It should be noted that juveniles in the custody of the Department of Corrections have been adjudicated as adults—but that label does not change the fact they are still under the age of 18 with the same vulnerabilities and ongoing brain development as their counterparts in the custody of DHHS. 14 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Sarpy County Juvenile Justice Center Sarpy County has not promulgated any policies which limit time that youth may be subjected to solitary confinement. Scotts Bluff County Detention Center ACLU of Nebraska | 15 EXAMPLES OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT USE IN NEBRASKA FACILITIES A young Nebraskan’s experience with solitary confinement is completely arbitrary and dependent upon the facility in which he or she is placed. For example, a youth who serves his or her time at the Geneva or Kearney Youth Rehabilitation Center could expect to spend no more than 5 days in solitary confinement, while a youth who spends his time at Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility could expect to spend up to 90 days in solitary confinement for a major rule violation. Solitary logs from Lancaster County Youth Services demonstrate the seemingly often arbitrary and subjective use of solitary confinement as a form of punishment. The lack of state-wide standards leaves facilities with far too much discretion, often resulting in the use of solitary confinement for improper or unnecessary purposes. These are among the more trivial reasons a youth has been placed in solitary. 16 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU of Nebraska | 17 USE OF SOLITARY CONFINEMENT IN NEBRASKA JUVENILE FACILITIES The ACLU conduced an open records request, asking each facility to provide logs showing length of stay and frequency of use of solitary for an 18-month period, covering January 2014 through June 2015. A full data table is available on page 31. NORTHEAST NEB JUVENILE SERVICES CENTER (in Madison County) County Facility, 2014-2015 Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) 1064 189.16 52 24 NEBRASKA CORRECTIONAL YOUTH FACILITY (in Douglas County) State Facility, 2014-2015 The Douglas County Youth Center and Scotts Bluff County Detention Center were unable to provide us with data about their use of solitary. Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) GENEVA SARPY State Facility, 2012-2014 County Facility, 2014-2015 Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) 54.24 43.78 5.1 6.17 Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) KEARNEY LANCASTER State Facility, 2012-2014 County Facility, 2014-2015 Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) 186 20.80 5 0.06 18 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Time Served in Solitary (days) Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) 2121.04 187.66 90 24 12.18 1.76 0.43 0.13 455.85 14.15 10 0.25 ACLU of Nebraska | 19 Jacob was a status offender who was put in the Douglas County Youth Facility on three occasions from the time he was 15 to 17. On each stay, he was placed in lockdown. His first stay in lockdown was “for his own good” because he had a broken ankle. What might have been a few weeks in lockdown turned into three months after he pounded the door and swore, begging them to release him—he was charged with “inciting a riot.” His second and third visits to solitary lasted over three months each and arose after he was attacked by older detainees who were gang members. Jacob received no therapeutic value from being placed in solitary confinement. He wasn’t regularly visited by a mental health counselor and says he wouldn’t have opened up even if he had been: “Therapy probably wouldn’t have worked—I wasn’t going to open up to the people who put me in a cage.” Douglas County had two forms of lockdown in 2008 during Jacob’s time there—one on a separate solitary unit and one in his normal cell where he could look out his window at his peers but not interact with them. “ It was 23 hours a day alone, no TV or radio. You were in there with one book, a blanket, a mat and a toothbrush. No art materials, no hobby items—everything was considered contraband. No classes or school while on lockdown. They’d bring you a packet of handouts but it was up to you whether you wanted to complete it or not. One hour a day, I’d be taken out and I could go to the gym but I was by myself even in the gym. I developed a pacing habit. I still do it now. I’d pace from one wall to the next. I’d pace and pace and imagine I was in one of the books I was reading. Nighttimes, you’d get a little crazy. They kept the light on and would wake us up every hour to check on you so you’d never get any good sleep. Jacob now volunteers as a mentor for troubled youth and children in foster care. He wants to ensure no other child spends long months in solitary: “ These kids weren’t born tough or angry. These kids were dealing with abandonment and depression and abuse. Lockdown brings out all these demons. And if you don’t know how to deal with demons—you’re a kid, you don’t even know how to deal with normal emotions yet—then you’re sitting there by yourself, nowhere to go and every negative thing you’ve been told about yourself seems to be coming true. Every time I look at the news, someone I was in jail with or someone I mentored is going to prison for life. They go to the system for correction—they go in as sheep—and they come out as wolves. If a factory pumped out a bad product over and over again, you wouldn’t blame the product, you’d go back to the factory and try to fix that 20instead. | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Jacob ACLU of Nebraska | 21 INVENTORY OF POLICY REFORM IDEAS AND SOLUTIONS Nebraska can and must do better for our vulnerable youth. Alternatives to solitary confinement produce positive results and less damage to children. As such, this report includes an inventory of best practices and successful models for reform that should be considered by Nebraska policymakers, thought leaders, regulators, and facility managers. National best practices for managing youth uniformly include strict limitations on the duration of and procedures for placing youth in isolation.23 The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends that solitary confinement be used only as an immediate safety mechanism.24 The Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative narrows that window to only 4 hours.25 This is because the negative effects of the prolonged isolation of youth, whether intended to protect or punish, far outweigh any purported benefits. Indeed, despite its pervasive use and well known harms, prolonged isolation serves no correctional purpose.26 There is no research to support the prolonged isolation of children as a therapeutic tool or to promote positive behavior. In fact, interactive treatment programs are more successful at reducing behavior problems and mental health problems in youth, while isolation provokes and worsens these problems.27 States all across the country are safely and successfully limiting the solitary confinement of juveniles in custody. Reports indicate that state juvenile justice agencies have implemented policy changes in recent years increasingly limiting isolation practices, with a majority of state agencies limiting isolation to a maximum of five days.28 Several of Nebraska’s neighboring states, including South Dakota29, Minnesota30, Iowa31, Missouri32, and Arkansas33 have policies that limit the use of isolation to five days or less. 22 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Six states – Alaska34, Connecticut35, Maine36, Nevada37, Oklahoma38, and West Virginia39 – by statute have limited certain forms of isolation in juvenile detention facilities. In some of these states, lawmakers have passed substantive bans on punitive isolation or on isolation for periods longer than 72 hours. In others, such as Nevada, strict reporting requirements have been implemented, to monitor the system-wide use of isolation. Meanwhile, other states have adopted more systemic models that eliminate the need for isolation. New York, for instance, has moved completely away from using isolation by implementing the “Sanctuary Model,” which emphasizes trauma-informed care in lieu of punitive responses to youth misbehavior.40 Recently, Illinois has taken an important and progressive step in prohibiting solitary confinement of juveniles, as well as implementing policies that tightly limit and regulate any separation of youths from the general population for safety reasons.41 Best practices suggested by the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative and the Performance Based Standards Initiative permit brief periods of isolation as long as they are supervised.42 The American Correctional Association standards would also permit solitary confinement but with approximately equivalent living conditions and privileges including more staff attention rather than less.43 Nebraska policymakers should consider establishing and implementing uniform statewide policies for the use of solitary confinement which can be applied to all our juvenile facilities. As more states begin to move away from solitary confinement for youth, Nebraska should consider banning solitary as ACLU of Nebraska | 23 well. Establishing clear policies, ensuring strong education and implementation efforts at the agency and facility level, and providing for effective ongoing oversight are critical elements of successful reform. Such legislation could include reforms that place limitations on when and how solitary can be used: §§ Solitary confinement is not to be used as a disciplinary measure or as punishment except after all other less-restrictive options have been exhausted, in extreme circumstances, which must be documented, and should not be used for four hours or longer. §§ Any juvenile placed in disciplinary or punitive room confinement must be provided due process protections, including the opportunity to know the reason for the decision, to appeal the decision in writing and with an advocate present. §§ Solitary confinement of a juvenile for longer than four hours should be approved by the director of the juvenile facility and documented in writing. A mental health professional should also provide an assessment of the youth placed in solitary confinement for over four hours. §§ The staff member who authorized the use of seclusion should file a written report with the head of the institution or facility setting forth the circumstances of the action and the reason for the use of seclusion. §§ Each juvenile facility should ensure clear documentation regarding the usage of solitary confinement, including all of the following data points: 1) The name and age of the person subject to solitary confinement. 2) The date and time the person was placed in solitary confinement. 3) The date and time the person was released from solitary confinement. 4) A description of circumstances leading to use of solitary confinement. 5) A description of alternative actions and sanctions attempted and found unsuccessful. §§ Mandating that all staff working in youth facilities have training in youth development, mental health, and de-escalation techniques as part of the academy and annual refresher training. Staff need more positive skills to deal with kids, especially kids with backgrounds of abuse and trauma, so part of reform is empowering staff to do their job better. 24 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska STATES THAT HAVE REFORMED JUVENILE SOLITARY Use of solitary limited to 5 days Use of solitary limited to certain offenses Moved away from solitary for youth ACLU of Nebraska | 25 CONCLUSION Solitary confinement and isolation of children is psychologically and developmentally damaging and can result in long-term problems and even suicide. Nebraska’s laws, policies, and practices must be reformed to ensure that conditions in the juvenile justice system are effective and safe – and that they prioritize protection and rehabilitation. Working together we firmly believe that meaningful reforms have the capacity to ensure improved conditions of confinement curing potential constitutional violations for Nebraska youth, mitigation of risk and legal liability for the State and counties which have jurisdiction over juvenile detention facilities, and most importantly improved outcomes for vulnerable children in Nebraska now and well into the future. 26 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU of Nebraska | 27 ENDNOTES 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (April 2012), https://www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/solitary_confinement_of_juvenile_offenders.aspx. Juvenile Detention Facility Assessment, Standards Instrument: 2014 Update. Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Voices for Children, Data Snapshot: Nebraska’s Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Centers (2015), available at http://issuu.com/voicesne/docs/yrtc_data_snapshot. Kids Count Data Center, a Project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation: Youth Residing in Juvenile Detention, Correctional and/or Residential Facilities (Oct. 2015), http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/42-youthresiding-in-juvenile-detention-correctional-and-or-residential-facilities?loc=1&loct=2#ranking/2/any/true/867/ any/17599. Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Juvenile Court Reporting, http://www.ncc. nebraska.gov/statistics/data_search/jcr.htm (last visited Nov. 18, 2015). Kids Count Data Center, supra note 4, at http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/42-youthresiding-in-juvenile-detention-correctional-and-or-residential-facilities?loc=29&loct=2#detailed/2/29/ false/36,867,133,18,17/any/319,17599. Kids Count Data Center, supra note 4, at http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/8391-youthresiding-in-juvenile-detention-correctional-and-or-residential-facilities-by-race-and-hispanicorigin?loc=29&loct=2#detailed/2/29/false/36,867,133,18,17/4038,4411,1461,1462,1460,4157,1353/16996,17598. Craig Haney, Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and “Supermax” Confinement, 49 Crime & Delinq. 124, 130, 134 (2003). Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2012), https:// www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/solitary_confinement_of_juvenile_offenders.aspx; see also Sandra Simkins, Marty Beyer & Lisa Geis, The Harmful Use of Isolation in Juvenile Facilities: the Need for PostDisposition Representation, 38 WASH. U. J.L. & POL’Y 241, 257-61 (2012). Id. at 259; see also Christopher J. Mumola, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 210036, Suicide and Homicide in State Prisons and Local Jails (2005), available at http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/shsplj.pdf. Andrea J. Sedlak & Karla S. McPherson, Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, NCJ 22729, Conditions of Confinement: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (2010), available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227729.pdf. Centers for Disease Control, “Effects on Violence of Laws and Policies Facilitating the Transfer of Youth from the Juvenile to the Adult Justice System,” (2007), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5609.pdf and “The Dangers of Detention,” Justice Policy Institute, (2006), available at http://www.justicepolicy.org/images/ upload/06-11_REP_DangersOfDetention_JJ.pdf. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, supra note 9. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, How Much Physical Activity do Children Need?, http://www.cdc.gov/ mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5609.pdf. American Academy of Pediatrics, Policy Statement: Health Care for Youth in the Juvenile Justice System, 128 PEDIATRICS 1219, 1223-24 (2011), available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/ early/2011/11/22/peds.2011-1757.full.pdf (reviewing the literature on the prevalence of mental health problems among incarcerated youth);Andrea J. Sedlak, Karla S. McPherson & Monica Basena, Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, NCJ 240703, Nature and Risk of Victimization: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (2013), available at http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/240703.pdf (finding that 56 percent of youth in custody experience one or more types of victimization while in custody, including sexual assault, theft, robbery, and physical assault). Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010) (outlawing life without parole for juveniles); Roper v. Simmons, 453 U.S. 551 (2005) (outlawing capital punishment for juveniles). Graham v. Florida, at 68. Jeff Goldman, N.J. To Pay Half of $400K Settlement over Solitary Confinement of Juveniles, The Star-Ledger, Dec. 10, 2013. Julie Bosman, Lawsuit Leads to New Limits on Solitary Confinement at Juvenile Prisons in Illinois, New York Times, May 5, 2015, at A11. For other lawsuits successfully resolved to limit or ban solitary confinement, see, e.g., Consent Decree, C.B., et al. v. Walnut Grove Corr. Facility, No. 3:10-cv-663 (S.D. Miss. 2012) (prohibiting solitary confinement of children); Settlement Agreement, Raistlen Katka v. Montana State Prison, No. BDV 2009-1163 (Apr. 12, 2012) (limiting the use of isolation and requiring special permission); Mo. Sup. Ct. Rule 129.04 app. A § 9.5-9.6 (2009) (placing limits on “room restriction exceeding twenty-four hours.)” For Ohio litigation, see DOJ 28 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 Summary of the Case and Settlement, http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2014/May/14-crt-541.html; see also Order, United States v. Ohio, No. 2:08-cv-475 (S.D. Ohio, May 20, 2014), available at http://www.childrenslawky.org/ wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Doc-400-1-Agreed-Order.pdf For New York litigation, see Stipulation for a Stay with Conditions, Docket No. 11-CV-2694 (SAS), Peoples v. Fischer, No. 2:11-cv-02694-SAS, Doc. 124 (Feb. 19, 2014 S.D.N.Y.), available at http://www.nyclu.org/files/releases/Solitary_Stipulation.pdf International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Arts. 10, 14(4), opened for signature Dec. 16, 1966, S. Exec. Rep. 102-23, 999 U.N.T.S. 171 (entered into force Mar. 23, 1976) (ratified by U.S. June 8, 1992) (“ICCPR”); Convention on the Rights of the Child, Arts. 3(1), 37, 40(3)-(4), opened for signature Nov. 20, 1989, 1577 U.N.T.S. 3 (entered into force Sept. 2, 1990) (“CRC”). The United States signed the CRC in 1995 but has not ratified the treaty. Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Interim Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ¶ 77, U.N. Doc. A/66/268 (Aug. 5, 2011) (by Juan Mendez), available at http://solitaryconfinement.org/uploads/ SpecRapTortureAug2011.pdf While theoretically young women adjudicated as adults will be housed in York at the women’s prison, there are few young female detainees at any given time so this report’s statistics only reflect the young men in custody at the Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility. See, e.g., American Correctional Association, “Performance Based Standards Juvenile Correctional Facilities” (4th ed. 2009); Performance Based Standards Learning Institute, “PbS Goals, Standards, Outcome Measures, Expected Practices and Processes” (2007), available at http://sccounty01.co.santa-cruz.ca.us/prb/ media%5CGoalsStandardsOutcome%20Measures.pdf; Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, “A Guide to Juvenile Detention Reform: Juvenile Detention Facility Assessment” (2014) at 117, available at http://www. prearesourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/library/aecf-juveniledetentionfacilityassessment-2014.pdf (“Staff never use room confinement for discipline, punishment, administrative convenience, retaliation, staffing shortages, or reasons other than a temporary response to behavior that threatens immediate harm to a youth or others”). American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, supra note 9. Voices for Children, supra note 3. See, e.g., Linda M. Finke, RN, PhD, Use of Seclusion is Not Evidence-Based Practice, 14 J. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 4, (2001), available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2001. tb00312.x/full; Steven H. Rosenbaum, Chief, Special Litigation Section, Remarks before the Fourteenth Annual National Juvenile Corrections and Detention Forum (May 16, 1999), available at http://www.justice.gov/crt/ special-litigation-section-cases-and-matters-1 Simkins et al., supra note 9, at 257-58. Performance Based Standards, Reducing Isolation and Room Confinement, at 4-6 (Sept. 2012), available at http://pbstandards.org/uploads/documents/PbS_Reducing_Isolation_Room_Confinement_201209.pdf. (“… very few state agency policies permit extended isolation time for youths and the majority limit time to as little as three hours and a maximum of up to five days.” at 4). South Dakota Department of Corrections: Juvenile Discipline System, available at http://doc.sd.gov/documents/ about/policies/Juvenile%20Discipline%20System.pdf Minnesota Department of Corrections: Discipline Plan and Rules of Conduct, available at http://www.doc.state. mn.us/DocPolicy2/html/DPW_DisplayINS.asp?Opt=303.010RW.htm. Iowa Administrative Code: Juvenile Detention and Shelter Care Homes, available at https://www.legis.iowa.gov/ docs/ACO/chapter/441.105.pdf Missouri Standards for Operation of Juvenile Detention Facility, available at https://www.courts.mo.gov/file/ AppendixA-JuvenileDetentionStandards02-14.pdf Arkansas Juvenile Detention Facility Standards, available at http://www.sos.arkansas.gov/rulesRegs/ Arkansas%20Register/2014/dec2014/006.26.14-002.pdf Alaska Delinquency Rule 13 (Oct. 15, 2012) (banning isolation of juveniles for “punitive” reasons, but defining “secure confinement” as permissible for “disciplinary” reasons and when there is a safety or security risk). Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 46b-133 (d)(5) (officials supervising children who have been arrested may not place “any child at any time” in “solitary confinement,” but the statute does not define “solitary confinement”); Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 17a-16(d)(1) (West 2014); Conn. Agencies Regs. § 17a-16-11 (2014) (for post-adjudication youth in Connecticut, the use of “seclusion” is governed by a statute and corresponding regulations requiring periodic authorizations and thirty-minute checks). Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 34-A § 3032 (5) (including segregation in the list of permissible punishments for adults, but not in the list for children; however, while state law prohibits “confinement to a cell” and “segregation” as punishment in juvenile correctional facilities, the state’s rules permit “room restriction” for juveniles, evevn for minor rule violations). ACLU of Nebraska | 29 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Nev. Rev. Stat. § 62B (children may be subjected to “corrective room restriction” only if all other less-restrictive options have been exhausted and only for listed purposes, and no child may be locked alone in a room for longer than 72 hours). Okla. Admin. Code, 377:35-11-4, Solitary Confinement (noting that solitary confinement of youth is a “serious and extreme measure to be imposed only in emergency situation”). W.V. Code §49-5-16a, Rules governing juvenile facilities (solitary confinement may not be used to punish a juvenile and except for sleeping hours, a juvenile may not be locked alone in a room unless that juvenile is “not amenable to reasonable direction and control.”); but see W.V. Div. Juvenile Serv., Pol’y No. 330.00, Institutional Operations, at 9, available at http://www.wvdjs.state.wv.us/Portals /0/Files/330.00%20-%20Resident%20 Discipline.pdf (permitting up to ten days room confinement as a sanction for some offenses). See Sanctuary Network, The Sanctuary Model, http://www.sanctuaryweb.com/network.php (listing systems and facilities that have adopted the Sanctuary Model for juvenile justice). Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, Discipline and Grievances, available at http://www.aclu-il.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/RJ-v-Jones-IDJJ-confinement-procedures-filed-4-20-15.pdf Performance Based Standards, supra note 28, at 4-6. American Correctional Association, Performance Based Standards Juvenile Correctional Facilities 51 (4th ed. 2009) (Standard 4-JCF-3C-01). Use of Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Juvenile Facilities Time Served in Average Length Longest Single Stay in Shortest Single Stay in Solitary of Stay in Solitary Solitary Solitary (days) (hours) (days) (hours) Lancaster (County Facility) 455.85 14.45 10.00 0.25 2014 314.55 14.92 10.00 0.25 2015 141.30 13.51 7.00 0.50 Sarpy (County Facility) 12.18 1.76 0.43 0.13 2014 6.39 1.60 0.43 0.13 2015 5.80 1.99 0.42 0.13 Northeast NE Juvenile Services Center (County Facility) 1064.00 189.16 52.00 24.00 2014 1064.00 189.16 52.00 24.00 Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility (County Facility) 2721.04 187.66 90.00 24.00 2014 1179.04 179.09 28.00 48.00 2015 1542.00 194.78 90.00 24.00 Kearney (State Facility) 186.00 20.80 5.00 0.06 2012 120.31 5.00 7.44 23.17 2013 1689.10 3.50 0.06 23.49 2014 17.15 2.55 0.67 15.73 Geneva (State Facility) 54.24 43.78 5.10 6.17 2012 40.43 5.10 24.27 83.33 2013 7.61 1.89 8.42 26.42 2014 6.20 1.99 6.17 21.58 The Douglas County Youth Center and Scotts Bluff County Detention Center were unable to provide us with data about their use of solitary. 30 | Growing Up Locked Down: Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska ACLU of Nebraska | 31 Growing Up Locked Down Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska 402.476.8091 gethelp@aclunebraska.org www.aclunebraska.org