Infamous Punishment The Psychological Consequences of Isolation, NPPJ,1993

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

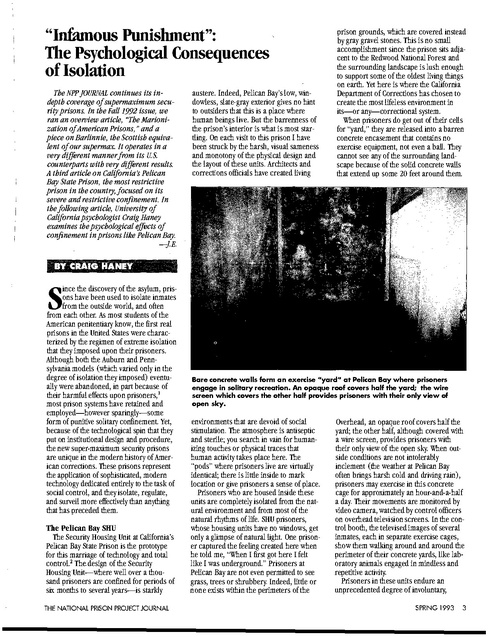

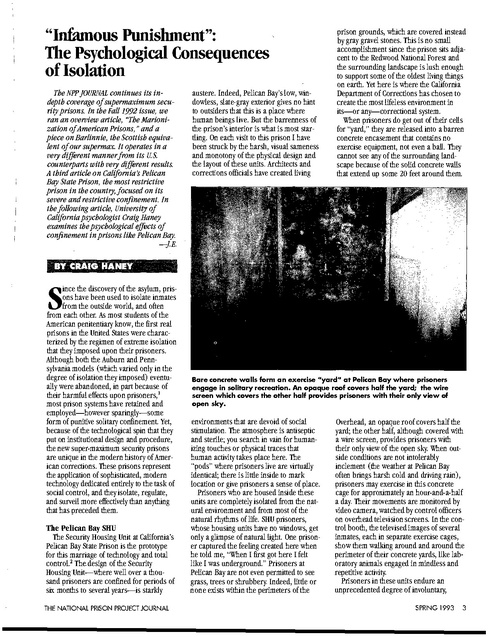

"Infamous Punishment": The Psychological Consequences of Isolation The NPP JOURNAL continues its in depth coverage of supermaximum secu rity prisons. In the Fall 1992 issue, we ran an overview article, "The Marioni zation of American Prisons," and a piece on Barlinnie, the Scottish equiva lent of our supermax. It operates in a very different manner from its U.S. counterparts with very different results. A third article on California's Pelican Bay State Prison, the most restrictive prison in the country, focused on its severe and restrictive confinement. In the following article, University of California psychologist Craig Haney examines the psychological effects of confinement in prisons like Pelican Bay. -JE. austere. Indeed, Pelican Bay's low, win dowless, slate-gray exterior gives no hint to outsiders that this is a place where human beings live. But the barrenness of the prison's interior is what is most star tling. On each visit to this prison I have been struck by the harsh, visual sameness and monotony of the physical design and the layout of these units. Architects and corrections officials have created living prison grounds, which are covered instead by gray gravel stones. This is no small accomplishment since the prison sits adja cent to the Redwood National Forest and the surrounding landscape is lush enough to support some of the oldest living things on earth. Yet here is where the California Department of Corrections has chosen to create the most lifeless environment in its-or any-correctional system. When prisoners do get out of their cells for "yard," they are released into a barren concrete encasement that contains no exercise equipment, not even a ball. They cannot see any of the surrounding land scape because of the solid concrete walls that extend up some 20 feet around them. B'Y CRAIG, HANEY S ince the discovery of the asylum, pris ons have been used to isolate inmates from the outside world, and often from each other. As most students of the American penitentiary know, the first real prisons in the United States were charac terized by the regimen of extreme isolation that they imposed upon their prisoners. Although both the Auburn and Penn sylvania models (which varied only in the degree of isolation they imposed) eventu ally were abandoned, in part because of their harmful effects upon prisoners, 1 most prison systems have retained and employed-however sparingly-some form of punitive solitary confinement. Yet, because of the technological spin that they put on institutional design and procedure, the new super-maximum security prisons are unique in the modern history of Amer ican corrections. These prisons represent the application of sophisticated, modern technology dedicated entirely to the task of social control, and they isolate, regulate, and surveil more effectively than anything that has preceded them. The Pelican Bay SHU The Security Housing Unit at California's Pelican Bay State Prison is the prototype for this marriage of technology and total control. 2 The design of the Security Housing Unit-where well over a thou sand prisoners are confined for periods of six months to several years-is starkly THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL Bare concrete walls form an exercise "yard" at Pelican Bay where prisoners engage in solitary recreation. An opaque roof covers half the yard; the wire screen which covers the other half provides prisoners with their only view of open sky. environments that are devoid of social stimulation. The atmosphere is antiseptic and sterile; you search in vain for human izing touches or physical traces that human activity takes place here. The "pods" where prisoners live are virtually identical; there is little inside to mark location or give prisoners a sense of place. Prisoners who are housed inside these units are completely isolated from the nat ural environment and from most of the · natural rhythms of life. SHU prisoners, whose housing units haye no windows, get only a glimpse of natural light. One prison er captured the feeling created here when he told me, "When I first got here I felt like I was underground." Prisoners at Pelican Bay are not even permitted to see grass, trees or shrubbery. Indeed, little or none exists within the perimeters of the Overhead, an opaque roof covers half the yard; the other half, although covered with a wire screen, provides prisoners with their only view of the open sky. When out side conditions are not intolerably inclement (the weather at Pelican Bay often brings harsh cold and driving rain), prisoners may exercise in this concrete cage for approximately an hour-and-a-half a day. Their movements are monitored by video camera, watched by control officers on overhead television screens. In the con trol booth, the televised images of several inmates, each in separate exercise cages, show them walking around and around the perimeter of their concrete yards, like lab oratory animals engaged in mindless and repetitive activity. Prisoners in these units endure an unprecedented degree of involuntary, SPRING 1993 3