Journal 21

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

INSIDE ...

AIDS in Prison

Self-help groups form inside the

walls

p. 14

Highlights

Recent NPP litigation

ISSN 0748-2655

NUMBER 21, FALL 1989

Directs Bail Fund to Be Provided

Court Fines Rhode· Island

Officials Over Non-Compliance

Mark Lopez

Of all the prisons and jails throughout

the country straining under the impact

of the move toward longer and/or mandatory sentencing, tiny Rhode Island's

unified prison and jail system is feeling

the heat the most. In 1988, its incarceration rate grew by an unprecedented

34%, nearly double the national average.

No relief appears in sight for 1989

either, as growth is expected to exceed

40%, according to the Bureau of justice

Statistics. Prison officials are at wit's end

trying to find bedspace and provide services for their bloated population. Under

pressures from the Department of Corrections, the public and the court,

Rhode Island's elected officials promise

relief, yet seem paralyzed when it comes

time' to deliver. Whatever headaches this

causes Rhode Island officials, however, it

cannot compare to the inhumanity suffered by 500 or so pretrial detainees

who are forced to live in facilities and

under conditions designed for one-third

as many people. On April 6, 1989, the

matter came to a head.

Senior U.S. District judge Raymond j.

Pettine held that Rhode Island officials

had failed to purge themselves of a previously entered contempt order' by

bringing their pretrial facility, the Intake

Service Center (ISq, into compliance

with the court's longstanding orders limiting its population. Substantial fines

were imposed, and the defendants were

Only an order holding [Rhode

Island] officials in contempt

would spur them out of the

bureaucratic quicksand in

which they had become mired..

p. 16

There comes a time, however, when

flexibility must give way to enforcement

lest one party's failure to comply undermines the viability of the agreement

which the parties reached and the court

approved as a workable solution to the

problems presented. 3

The district court's decision to adjudge Rhode Island officials in contempt

was necessary to head off a "societal disruption" of serious magnitude, according

to judge Pettine. Only an order holding

these officials in contempt would spur

them out of the bureaucratic qUicksand

in which they had become mired, and

force them to take the action necessary

to meet the standards established in the

consent decree. 4

On August 17, 1989, in a per curiam

opinion, the First Circuit affirmed judge

Pettine's order in all respects for the

reasons set out in the district court's

two comprehensive opinions, supra. s

History of the Case

Mark Lopez is a staff attorney with the

National Prison' Project

Anyone remotely familiar with the hisdirected to use the accumulated monies

tory of the Rhode Island Adult Correcto prOVide bail for indigent low-risk pre- tional Institutions (ACI) knows that until

trial detainees, thereby effecting an imthe litigation of the late I970s it ranked

mediate reduction in the population at

.as one of this country's most antiquated

ISC. 2

and poorly managed prison systems. By

The state immediately appealed and

most accounts, prison officials had lost

was granted a stay by the First Circuit

control as violence and squalor beset the

Court of Appeals. On the appellate

prison. Nowhere was the impact felt

court's own motion, the appeal was exmore harshly than on the lives of pre-.

pedited and argument was heard in early trial detainees:

june. The stay was dissolved by the

The conclusion is inescapable that precourt of appeals shortly after the appeal

trial inmates are not provided minimally

was argued. The state raised the usual

adequate protection against assault, that

federalism complaints about the scope

they are exposed to punishment even

and intrusiveness of the relief granted by

worse than that endured by other inthe district court. In the ordinary case,

mates, and that they are incarcerated

perhaps they might have cause to comunder conditions far harsher than anyplain. But, no one who carefully studies

thing necessary to guarantee their presthe long history of this case can fail to

ence at trial.

.

see how fleXibly the district court has

Palmigiano

v.

Garrahy,

443 F.Supp.

treated its orders, precisely because it

956, 971 (D.R.I. 1977).

has the utmost respect for the varying

To alleviate the fear and suffering of

competencies of different branches of

pretrial detainees, the 1977 order regovernment as well as the differing

quired the state to remove all such perneeds and interests of the parties. For

-continued on next page

these reasons, it has repeatedly modified

and amended the orders at issue in response to the state's pleas for fleXibility.

3700 F.Supp. at 1193.

'Polm;g;ono v. Gorrohy, 700 F.Supp. 1180 (D.R.1.

1988).

2Polm;g;ono v. Gorrohy. 710 F.Supp. 875 (D.R.1.

1989).

. .

..

•

4/d.

SPolm;g;ono v. O;Prete, No. 89-1 +40 (I st Cir.

8117/89).

•

•

•

-continued from front page

sons from the existing Maximum Security Facility within three months and to

house them separately thereafter, with

no subsequent intermingling or contact

between detainees and sentenced

prisoners.

The Emergence of Overcrowding

at the ISC

Despite the explicit terms of the 1977

Order and the three-month timetable

that it announced, it was not until five

years later, in July 1982, that the state

succeeded in achieving full compliance

with the order's requirements for the

housing of pretrial detainees. With the

opening of the ISC in 1982, however,

detainees were at last no longer intermingled with sentenced offenders and

the constitutionally required physical

conditions imposed by the 1977 order

were momentarily met. Nevertheless,

old problems persisted and new problems loomed. In a "final report" on

compliance with the 1977 order issued

on October 20, 1983, the Special Master

appointed by the court to monitor the

ACI noted the overcrowding in the

newly opened facility. On the day it was

first occupied, one hundred of the ISC's

168 single occupancy cells were already

fitted with double bunks, and the facility's population consistently topped 200.

At the time of the Special Master's report, nearly 250 detainees were being

held in the ISC, and all concerned conceded that the magnitude of the overcrowding problem would only continue

to worsen.

[The state] fell into a

frustrating pattern of doing too

little too late.

Despite these early indications that

overcrowding would grow dramatically

worse, the state repeatedly failed to try

to solve the problem. Instead, it fell into

a frustrating pattern of doing too little

too late, and only after prodding by the

district court's many subsequent orders

designed to ameliorate the devastating

impact of overcrowding at the ISC. In

1985, for example, the court held an evidentiary hearing to examine the overcrowding crisis at the ISC and its impact

on the basic conditions of confinement

at the facility. The evidence adduced at

the hearing painted a disturbing portrait

of life inside the overstuffed facility.6

The court's frustration with the

state's intransigence was unmistakenly

·Palmigiano v. Garrahy. 639 F.Supp. 244 (D.R.1.

1986).

2

FALL 1989

It.

Senior U.S District judge Raymond j. Pettine

presided over the Palmigiano case from 1976,

when it was first fi'ed, until /989. He repeatedly urged state officials to remedy the hazardous overcrowding in Rhode Island's prisons.

"I have cajoled and waited as

though for Godot"-Judge

Raymond j. Pettine

expressed in its order growing out of

that hearing and imposing a 168-person

limit on the number of detainees in the

ISC:

The record shows that for nine years

this Court has employed all the artifices

it could conceive to have the defendants

cure the many constitutional violations it

found. I have been imperious, didactic,

and supplicatory; I have cajoled and

waited as though for Godot I have ever

been reluctant to interfere with the operation of the prison. However, the pattern is always the same: without monitoring, prison officials permitted the

kitchen to get into a deplorable state

. .. they failed to prOVide adequate medical staff for an increase in population of

which they have been aware for years;

indeed, repeated warnings from the Special Master have been in vain . . . even

in the areas that could easily have been .

corrected, nothing has been done ...

the veritable fortune that has been

poured into that institution will all be for

naught if positive firm steps are not immediately invoked.

The overcrowding must be confronted

before it becomes uncontrollable. A delay under the present conditions can

give rise to problems of staggering

magnitude. 7 Current Overcrowding at ISC

Today, 12 years after the original order,

years after overcrowding was first identified as critical at the ISC, and more

'Id. at 258; the cap was later increased to 250 persons by agreement of the parties.

than three years after the 1986 reaffirmation of the court's entire course of

dealing in this -case, Rhode Island officials

are still frozen in place, unable or unwilling to generate an effective response.

The overcrowding at the ISC in recent months is more serious than it was

in December 1985, when the court

heard the testimony which resulted in its

May 12, 1986 Opinion and Order. On

December I, 1985, the population was

289, while on June 12, 1988, the population went up to 394. On February 20,

1989, the most recent deadline imposed

by the court, it still hovered at 390, and

on March 29, 1989, just days before the

court sanctioned the state, the population stood at 473. Since that time it has

housed an average population of 500 or

more. Thus, the present population at

ISC is three times the design rated capacity of 168, and double the population

ceiling of 250 agreed to by the parties.

1988 and 1989 Orders of Contempt

Confronted by the rising population, the

plaintiffs moved the court to adjudge the

defendants, the Governor of Rhode Island, and the director of the Rhode Island State Department of Corrections,

to be in civil contempt of three standing

orders of the court governing the housing of pretrial detainees at the ISC.

Plaintiffs' essential complaint was that

the Rhode Island officials were grossly

exceeding the population limit of 250.

As a coercive sanction, the plaintiffs

sought the imposition of fines and the

establishment of a bail fund, using these

funds to provide bond for the hundreds

of low-bail pretrial detainees who were

choking the system.

111

JOURNAL

OF THE

NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT

Editor: Jan Elvin

Editorial Asst.: Betsy Bemat

Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director

The National Prison Project of the

American Civil Uberties Union Foundation

1616 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 331·0500

The National Prison Project is a tax-exempt foundation·

funded project 0( the ACLU Foundation which seeb to strengthen

and protect the rights 0( adult and juvenile offende'" to improve

ovenJl conditions in correctKxlal facilities by using existing administrative. legislative and judicial channels; and to develop a1.

ternatives to incarceration.

The reprinting of jOUfWAL material is encou"lled with the

stipulation that the National Prison Project jOUfWAL be credited

with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint be sent fO the

editor.

The jOUfWAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by !he

National Prison Project. Materials and suggestions are welcome.

The National Prison Project jOUfWAL is designed by James

True. Inc.

1

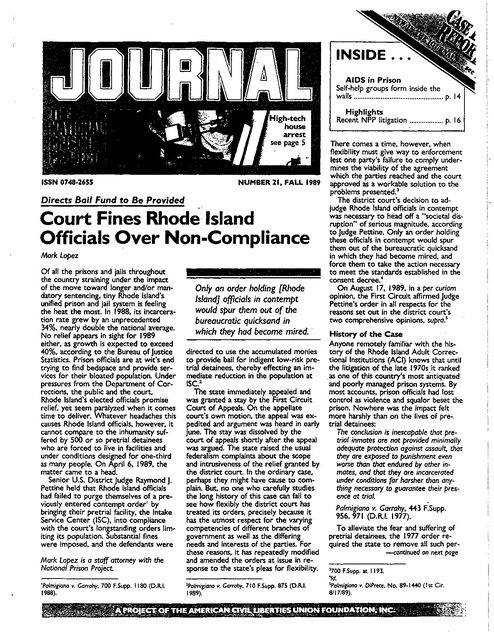

The recreation area for the A block at the Adult Correctional Institution in Rhode Island also contains beds for prisoners because of the severe

overcrowding.

In support of its position, plaintiffs

were able to point to the numerous

cases in which federal courts. in recent .

years, had not hesitated to exert the

power of contempt to coerce recalcitrant jail and prison officials to comply

with overcrowding orders. These cases

are testaments to the severe overcrowding crisis in this country. and are

at the same time evidence that the limits

of judicial tolerance have been reached. 8

The defendants countered that the

court should stay its hand because compliance with the population orders was

"Inmates of Allegheny County jail v. Wecht, 874 F.2d

147 (3rd Cir. 1989); Twelve john Does v. Distria of

Columbio, 855 F.2d 874 (D.C. Cir. 1988); Badgley

v. Santacroce, 800 F.2d 33 (2nd Cir. 1986); Morales

Feliciano v. Hernandez-Colon, 697 F.Supp. 26

(D.P.R. 1987); Albro v. Onondaga County, N.Y., 681

F.Supp. 991 (N.D.N.Y. 1988); Tate v. Frey, 673

F.Supp. 880 rN.D. Ky. 1987); United States v. State

of Michigan, 680 F.Supp. 928,1047·1054 rN.D.

Mich. 1987) (bench opinion of May 22 and May 28,

holding defendants in contempt); jackson v. Whitman, 642 F.Supp. 816 (D.La. 1986); Ruiz v. McCotter, 661 F.Supp. 1/2 (S.D. Tex. 1986); Toussaint

v. McCarthy, 597 F.Supp. 1427 (N.D. Ca. 1984);

Mobile County jail Inmates v. Purvis, 581 F.Supp. 222

(S.D. Ala. 1984); Miller v. Carson, 550 F.Supp. 543

(M.D. Fla. 1982).

The state completely

neglected to use less

burdensome measures ...

to alleviate overcrowding.

impossible given the unprecedented

growth caused by stricter bail and sentencing laws and the failure of the legislature to create new bedspace.

The Court's Response

While it is true that a finding of civil

contempt can be deflected by a showing

that compliance with the court's order

is factually impossible,9 the record in this'

case belies the state's claim. The evidence showed that Rhode Island officials

failed to achieve substantial and diligent

compliance with the district court's orders. For years Rhode Island had been

'U.S. v. Rylander, 460 U.S. 752, 757 (1983). If the

party sought to be held in contempt is literally un·

able to comply because compliance is not presently

within his power, the attempt at coercion embodied in a finding of contempt is meaningless. Shillitani v. U.S., 384 U.S. 364, 371 (1966).

aware of recurrent overcrowding at ISC.

and had not taken steps to eradicate the

problem. Not only had the state failed

to create sorely needed new space in

spite of its already swollen population

and projections for dramatic population

increases, it completely neglected to use

less burdensome measures available to it

to alleviate overcrowding. Most notably,

no pretrial diversion services are available to Rhode Island courts. These services would significantly reduce the number of detainees without creating a risk

to the public.

As a result of the state's inertia, there

are large numbers of persons detained

on bonds so insignificant that it seriously

calls into question the justification for

their confinement, except that they are

too poor to make bail. As hoped by the

plaintiffs, the district court's response to

the state's request for yet another

chance was short, but to the point:

Given this long history of delay, it is disingenuous for defendants to continue to

plead that the problem has grown too

overwhelming to deal with after systematically refusing to address this visibly

brewing crisis for so long. Such a blatant

--continued on next page

FALL 1989

3

--continued from previous page

. attempt to avoid responsibility for their

own patently apathetic behavior will not,

at this late date, rescue them from its

consequences. '0

The district court's conclusion is directly supported by the holdings of

three recent court of appeals decisions,

applying the test of impossibility to the

conduct of state officials in prison overcrowding cases. These courts have been

particularly strict in their interpretations

of this defense. The Third Circuit interpreted the defense of impossibility to

mean "physical impossibility beyond the

control of the alleged contemnor."11

"[T]he suggestion that it was physically

impossible for the Allegheny County to

obey the order in the respects in which

they were held to be in contempt is

sophistical. The county officials simply

chose to take no steps to provide the

warden and his staff the wherewithal to

comply."12

Similarly, the Second Circuit has held

that the impossibility defense is not

available where county defendants' compliance is hindered by political difficulties,

rather than physical impossibilities, in alleviating jail overcrowding. Il The court

held that the defendant county officials

could comply with a court-ordered cap

simply by refusing to accept more prisoners, and rejected the officials' argument that a refusal to accept new prisoners might place them in contempt of

sentencing state courts. The court stated

that the federal court's order regarding

prison population would be entitled to

obedience under the Supremacy Clause,

and that if a state court attempted to

hold the county in contempt, the federal

judgment "would provide a complete

defense." The court found this to be

true even though the judgment had been

entered by consent.'4

In concert with the Second Circuit, in

Twelve John Does v. District of Columbia,'s

the D.C. Circuit held that it would be

inappropriate to allow prison officials to

escape their obligations to reduce the

prison population by pleading impossibility. The court brushed aside the defendants' claim that significant increases in

the numbers of arrests and inmates precluded it from staying within the population limits. It also showed no sympathy

for the claim that political difficulties

prevented the construction of new prisons. In the end, the court held that conditions such as these do not establish a

. '''700 F.Supp. at 1197.

"Inmates of Allegheny County Jail v. Wecht, 874

F.2d at IS2.

12ld.

'3See Badgley v. Santacroce, 800 F.2d at 36·38.

'·'d. at 37·38.

"855 F.2d 874.

4 FALL 1989

125 persons have been

released under the [Rhode

Island] bail release program.

lack of power to alleviate the overcrowding, even if that means release of

or refusal to accept prisoners. 16 judge

Pettine found no basis for departing

from this persuasive line of authority.17

The Sanctions

There is no question the federal courts

are authorized to impose heavy fines for

failure to comply with prison overcrowding orders,18 and in the ordinary

case, the prospect of being confronted

with heavy fines might compel compliance with a court order imposing a population ceiling. 19 This is not an ordinary

case, however, and the history and record of this litigation indicates that fines

alone would not suffice to reduce the

population. Rhode Island officials have

been admonished and threatened with

heavy fines before, and have chosen to

ignore the warnings. For this reason, the

district court directed that any fines collected from the state officials as a result

of further dilatory conduct in reducing

"Id. at 877.

17Rhode Island's attempt to introduce evidence of

good faith, diligence and Eighth. Amendment con·

siderations by arguing that conditions were constitutional despite the overcrowding proved equally

unavailing. The district court correctly opined that

good faith is not a defense to civil contempt, McComb v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 336 U.S. 187, 191

(1949), and that contempt proceedings do not

open to reconsideration the legal or factual basis

of the order alleged to have been disobeyed and

thus become a retrial of the original controversy.

700 F.Supp. at 1195, citing Maggio v. Zeitz, 333

U.S. 56, 69 (1949). Prison overcrowding cases supporting this propoSition include Twelve John Does v.

District of Columbia, 855 F.2d at 878, n.30; Badgley

v. Yarelas, 729 F.2d 894, 899 (1984); Ruiz v. McCotter, 661 F.Supp at 125.

'·See Inmates of Allegheny County Jail, 874 F.2d at

152 ($25,000 fine); Twelve john Does, 8S5 F.2d at

875-876 (imposition of population cap and fine of

$2S0 per day for each dorm at which the limit was

surpassed); Badgley, 800 F.2d 33 (fine of not less

than $5,000 for each inmate admitted over population cap).

"Numerous district court decisions have done the

same. See cases cited n.8, supra.

the population be set aside to finance a

bail fund to be used for pretrial detainees under certain terms and conditions

to be developed later. 2o

The Supreme Court has recently recognized the authority of a district court

to utilize fines collected under a contempt sanction to assure compliance

with the court's orders. In Local 28 of

Sheet Metal Workers v. ££O.C.,2' the

Court upheld the district court's imposition of contempt sanctions, including a

fine to be used in a fund designed to increase nonwhite membership in a union

apprenticeship program. The Court

noted that the district court had "carefully considered" the proper standard in

exercising its broad remedial powers

and imposing the fines, and that the district court had properly concluded "that

the Fund was necessary to secure [defendantsl compliance with its earlier

orders."h

Even before Local 28 was decided,

federal courts have ordered the payment

of funds into a bail fund to relieve overcrowding of pretrial detainees. For instance, in Mobile County Jail Inmates v.

Purvis,23 an Alabama federal district court

ordered the county officials to pay into

the court accumulated contempt fines,

and the court used the fines to provide

fees to pay bail bonds for low-bond pretrial detainees. The court noted that, despite its reluctance to involve itself in

such matters, it "must find some way to

achieve compliance with its orders. Although the court has given the defendants over two years in which to find and

implement the solution, they remain far

from compliance."24 Significantly, in deciding to establish the. bail fund with accumulated fines, the court relied on U.S.

District judge Morris Lasker's order in

the Rikers' Island case, Benjamin v. Malcolm,2S in which he ordered $2,000,000

in accumulated fines to be used to pay

for certain low-bond pretrial detainees

not charged with violent crimes.

The success of this approach is perhaps no more evident than in Philadelphia where city officials have been required to prOVide bail for the larrest

numbers of low-bond detainees? The

2"710 F.Supp. at 887.

2'478 U.S. 421,106 S.Ct. 3019 (1986).

221d.

23

581 F.Supp. 222 (S.D. Ala. 1984).

24/d. at 225.

liNo. 75 Civ. 3073 (S.D. N.Y. 1983).

USee also, Harris v. Perns/ey, No. 82-1847 (ED. Pa.

6/6/88) (instructing Philadelphia officials to provide

BailCARE screening process in place

there is comprehensive. All inmates released through the program have to satisfy requirements relating to lack of serious criminal record. references. verified

residence and surety. If the bailee does

not comply with the terms of release.

such as drug. alcohol or employment

counseling. bail is revoked and the inmate is returned to prison pending trial.

The BailCARE program has been working extremely well. As of January 31.

1989. 22.059 cases were reviewed and

1.321 inmates were released by BailCARE. The program has placed 1.288 inmates in treatment. training and education programs. The rate of appearance in

court of those released through the program through December '31. 1988 was

88%. Upon appearance in court, only

39% of BailCARE cases have resulted in

conviction. 27

The evidence is not all in yet in

Rhode Island where 125 persons have

been released under the bail release

program. The experience in Philadelphia,

however. is compelling evidence of how

safe and effective this sanction is for

achieving compliance with court-ordered

population limits. We are hopeful that

this success can be repeated in Rhode

Island. 28

Conclusion

During the long and tortuous history of

this case. Rhode Island officials have

done nothing to remedy constitutional

violations except when they were

coerced into doing something by the

court. Left to their own devices, they

have exceeded the design capacity of

168 at the ISC, they have exceeded the

cap of 250 that they agreed to, they

have gone to 300, 350, 400, 450, and

500, and, unless reigned in, they will

surely go above 600 in the foreseeable

. future. They will continue to jam human

bodies into this facility until, like the overstuffed suitcase, it bursts at the hinges.

Judge Pettine unquestionably acted correctly in an effort to enforce his order

and to prevent the situation from ending

in tragedy. •

funds sufficient to obtain the release of low·bond

pretrial detainees).

27Harris v. Per.'1s/ey. No. 82-1847 (available on Westlaw: WL 16269) (order expanding pool of eligible

detainees).

28Similar court-ordered bail programs to alleviate

overcrowding in county jails are also in place in

Puerto Rico and Newark. New Jersey. Morales Feliciano v. Hernandez Colon. No. 79-4 (PG) (D.P.R.

4/28/88); Essex County Jail Inmates v. Fauver, Civ.

No. 81-1945 (D.N.J. 5/10/89).

Electronic Monitoring:

Humane Alternative or Just

Another "Gizmo"?

Russ Immarigeon

"Opposition to the beepers has been

sparse. Civil libertarians seem split on

the issue. At a national ACLU convention, I took an unscientific, informal poll

among activists I met Though many

said beepers herald an Orwellian state •

of affairs, others argued that beepers

represent a humane alternative to institutional confinement Such ambivalence

is understandable. One can hardly second-guess the prisoner who would rather

surrender a modicum of privacy at home

than.1ose all privacy. At the same time,

though, beepers appear beneficent only

because our existing correctional system

is so horrible. Beepers can be justified

only because Americans have not embraced solutions to crime that go beyond

isolating criminals in metal cells."

Community supervision was

often seen as nothing more

than a slap on the wrist

program. Recently, an internal department of corrections management information paper found that probation officers did not perceive electronic

monitoring "to improve the level of supervision over the surveillance prOVided

by IPS in any meaningful way, since curfew checks routinely performed by IPS

officers was thought to be very effective

in keeping track of probationers' whereabouts."2 The report recommended that

electronic monitoring not be used as an

additional form of surveillance in IPS

-Keenen Peck, former chairperson,

cases.

Capital Area Chapter of the ACLU

Georgia has not yet decided to abanof Wisconsin I

don its use of electronic monitoring;

Nonetheless, the report is important beThe electronic monitoring of criminal of- cause it is the first empirical evidence

fenders, first proposed in the mid-I 960s

expressing dissatisfaction about the social

as a visionary method of keeping certain

policy of using electronic monitoring as a

offenders from being imprisoned. never

method of meeting particular prograril

really caught on until twenty years later

objectives. Previous research findings

when states such as Florida, Georgia,

placed heavy emphasis not on its approMichigan and Texas, mired deeply in sky- priateness or even its effectiveness but

rocketing prison populations, began using on the technical adequacy of monitoring

it to augment their intensive and comde.vices manufactured by various

vendors.

munity supervision programs.

Strong support still exists for elecGeorgia Report Calls for Halt in

tronic monitoring. At the federal level.

Use of Electronic Monitoring

for instance, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, the National Institute of Justice, .

In the 1980s, Georgia became a bellwether state for criminal justice reforms' the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and the

U.S. Parole Commission are all now enthrough its use of intensive supervision,

couraging, implementing. and/or evaluatboot camp, and other initiatives. Like

ing its use. Some states, like New Jersey

many Southern states, Georgia has aland Utah, remain committed to using it.

ways relied heavily on imprisonment.

Other states, such as Maine and New

However. overwhelming prison populaYork. are either considering using it, or

tions, the threat of court intervention,

have demonstration projects which they

several state study commissions, and an

are evaluating to see if further use is

innovative probation division have

turned Georgia into a state which every- warranted.

However, because of Georgia's leadone, including many Northern states, lisership in recent years in criminal justice

tens to when it acts.

Georgia started using electronic moni- innovations, this finding is likely to spark

discussion about the relative merits and

toring several years ago to augment its

further use of electronic monitoring

intensive probation supervision (IPS)

devices.

-<ontinued on next page

Russ Immarigeon, a regular contributor to

NPP JOURNAL, lives in Portland, Maine.

'Keenen Peck. "High-Tech House Arrest," The

Progressive. 2(7). Ouly 1988). p.26.

2Billie S. Irwin, "IPS with Electronic Monitoring

Option." (Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of

Corrections), (April 1989). p.16.

FALL 1989

5

-continued from previous page

Electronic Monitoring Spreads

Across the Country

In the 1980s, criminal justice policymakers were forced to take a careful look at

how probation and parole agencies could

help alleviate prison overcrowding. In

the process. these agencies were frequently put on the defensive. Long ignored, community supervision was often

seen as nothing more than a slap on

the wrist and, right or wrong. efforts

were set in motion to strengthen (or

"toughen up") the image and services of

these agencies.

This "credibility crisis" prOVided fertile soil for electronic monitoring. According to the National Institute of justice., which has closely monitored its

growth, 21 states used electronic monitoring to supervise 826 offenders in

1987; by 1988, electronic monitoring

expanded to 33 states supervising 2,277

offenders, a three-fold increase from the

previous year. Florida and Michigan alone Electronic monitoring, in use in 33 states, always accompanies another form of correctional interaccount for nearly one-half of these

vention such as house arrest or intensive supervision.

electronically-monitored offenders.

Electronic monitoring is used under a

jail overcrowding was not reduced by

•

variety of arrangements: in federal, state,

the program; only three of 35 offenders

Researchers found that jail

county and private agencies; by pretrial,

were terminated from the program but

probation, and parole agencies; and by

none were violated for new crimes; disovercrowding was not reduced

adult as well as juvenile offenders. It is

trict

court judges reported they did not

by the [electronic monitoring]

never used as a sole sanction; instead, it

use home incarceration as an alternative

program.

always accompanies another form of corto jail; and, nevertheless, the program

rectional intervention (house arrest,

was not used as a method of "widening

home confinement, intensive supervision,

the net of social control."s

urine testing, etc.). Indeed, some observ- in Indiana and Oklahoma. However, no

Offenders participating in a house arers argue that electronic monitoring

evidence currently exists telling us if

rest/electronic monitoring program in

should be viewed as just a surveillance

electronic monitoring prevents or deters Clackamas County. Oregon were monitored, on average, for 33 days. They

technology. used to support another

crime, decreases or increases the seversanction, and not as an intermediate or

achieved a highly successful completion

ity of imposed sanctions. or affectS pubother type of sanction. In any case, oflic safety.

rate (90%) and only one of the ten profenders are monitored by either active

gram violators committed a new crime.

"The limits of electronic monitoring

or passive systems and, on average, they

The study found that electronically monare evident." a recent New York study

are supervised for a short period of time reported. "No EM system can give initored offenders were less likely to re(in 1988, $Iightly more than half of these formation on a defendant's activities

cidivate than work release offenders.

offenders were supervised for six weeks

within the house. No system can track

However, post-treatment periods of obor less). In most programs, offenders pay what the defendant is doing during the

servation were different for both groups

various fees or charges (up to $15 per

time he is scheduled to be at work. Fur- and nearly all of the re-arrests were for

day). In some programs, as many as half

petty crimes, Le., probation violations,

ther. a passive monitoring system allows

its clients fail to meet program requirethe real chance that a defendant may

misdemeanor disturbances, and traffic ofments; however, infractions of program

leave his home without authorization

fenses. The cost of electronic monitoring

and never be detected.....

rules, rather than new crimes, are the

fell in between regular probation and jail

most common reason for violation. 3

incarceration.6

A brief review of several other studIn short, these studies have no comies suggests some of the limits and conparison group and they rely on informatradictions of electronic monitoring.

Research Findings on Electronic

tion from a small number Qf cases inOffenders participating in a home inMonitoring

carceration/electronic

monitoring

proComprehensive research on electronic

'J. Robert Lilly. Richard A. Ball, and Jennifer

gram in Kenton County, Kentucky bemonitoring is scarce. A number of indiWright,

"Home Incarceration with Electronic

May

1985

and

December

1986

tween

vidual programs have conducted or

Monitoring in Kenyon County, Kentucky: An Evalwere primarily male, nonviolent propsponsored evaluation research concernuation," in Belinda R. McCarthy (ed.), Intermediate

erty offenders. Researchers found that

ing program implementation, and the

Punishments: Intensive Supervision, Home ConfineNational Institute of justice has funded

ment, and Electronic Monitoring, (Monsey, NY:

evaluations of electronic monitoring use

'Martin B. Mcindoe and Patrice Dlhopolsky. "SufCriminal Justice Press). (1987), pp.189-203.

3Annesley K. Schmidt, "Electronic Monitoring of

Offenders Increases." Nlj Reports, No. 212 Oanuary/February 1989). pp.2-S.

6

FALL 1989

folk County Probation Department Electronic

Monitoring Demonstration Grant: First Year Evaluation (1988-89)," (Yaphank. NY: Suffolk County

Probation Department), (1989).

"Annette Jolin. "Electronic Surveillance Program

Clackamas County Community Corrections Evaluation," (Oregon City, OR: Clackamas County Community Corrections). (1987).

volving low-risk offenders. Nevertheless,

research on electronic monitoring, like

the intervention itself, raises some curious questions. On the one hand, we still

know very little about the effects of

electronic monitoring. The Georgia

study mentioned earlier is perhaps the

only investigation which uses control

group data (data for this study were collected as part of a multi-state study of

intensive supervision programs being

conducted by The Rand Corporation). It

suggests direct supervision by probation

officers is potentially more effective than

supervision by technological device. This

fits well with what many practitioners

are saying. "Frankly stated," a probation

official in New York recently argued,

"the primary need for improving probation outcomes is to increase human resources--more officers, not just more

gizmos."

On the other hand, because electronic

monitoring seems to offend our sense of

civil liberties in a way that human forms

of intervention do not, questions (such

as the influence of electronic monitoring

on the families of offenders or even the

clarity of purpose of this form of supervision) are being raised simply because 'of

this discomfort. While this is true for

other interventions as well, observers

are asking questions which have not yet

been answered. Electronic monitoring is

being used in vastly different circumstances, anc;l sufficient comparative research

has not yet been done.

We don't know if electronic

monitoring is prodUcing more

problems than it may be

solving.

We do not yet know if electronic

monitoring is needed to change criminal

behavior. Moreover, we don't know if

electronic monitoring is producing more

problems than it may be solving. With

increased surveillance, more offender violations (not necessarily new crimes)

will naturally occur. Do we want to

have a system which measures success

by the number of immediate failures it

captures rather than the number of

long-term successes it produces~

The future role of electronic monitoring in the administration of criminal justice remains uncertain. What can be said

is that electronic monitoring has neither

reduced correctional crowding nor lessened U.S. emphasis on incapacitation.

At present, few clear statements of

policy exist concerning the use of elec·

tronic monitoring. The American Civil

Liberties Union, the American Correctional Association, and the American

Probation and Parole Association have

discussed or are working on policies but

none currently exist. The American Bar

Association is apparently the only national criminal justice organization to

have promulgated any standards for the

use of electronic monitoring. FollOWing

lines set by the ABA Standards for Criminal Justice. the ABA Section on Criminal

Justice cautiously posits that I) electronic monitoring be the least restrictive

alternative, 2) it not be reqUired as a

condition of probation, and 3) a person

should not be forced to pay for it.?

State-level advocacy organizations are

also wary about using electronic monitoring. The New York Campaign for

Common Sense in Criminal Justice, for

instance, suggests that electronic monitoring should not be used for pretrial

defendants, for offenders who would not

ordinarily receive an incarcerative sentence, or without "support services that

can help participating offenders develop

the skills and personal resources needed

to lead a crime-free Iife."s

American Bar Association Criminal Justice Section.

"Principles for the Use of Electronically Monitored

Home Confinement as a Criminal Sanction," (August 1988). pp.I-2.

"The Campaign for Common Sense in Criminal Justice can be reached at the Correctional Association of New York. 135 East 15th Street. New

York, NY 10003.2121254-5700,

7

-continued on next page

A Brief History of,. , J

. . ° M °t • . · , r "

.'EI

. ect r:()nlc.. om On~~;):;,~;;

Ralph Schwitzgebel's electronic,.'~.~.!

monit()ring device never caught on... '"

By thelllid.1980s, however, rapidly ;::;'c~

.'

. ' .. . .

\'»* 'rising'jail and prison populations,.:,'~:~

.' . The use of electronic mOlli't()~i~g;"';-loomed large in most jUrisdictions.;,.;)C'i

'for the supervision or surveillarlce .o~';

Criminal justice policies, partic~larlyt;:;;~

criminal offenders was first champi.. :.. . on volatile issues like prison use, have:)~~

. , onedin law and behavioral science ... .

centered on politically safe solutions.;;i~l

journals just more than twenty years ,

In. this con.text; elect

.. rooni.c.•. ·monit..or.ilig.. ·;~~J~.;

ago. Ralph K. Schwitzgebel, the bestbecame very attractive becauseState!;i:it~

known early advocate, saw these de· . . and loCal governments could stilf.· ;:F.tt~

.

~~~ngasren.:=:ti:::;::=.~~~.

~ O~~.~'= i~~i~.n~.i~. ~.ta~ 7y.•,: ':.•~.~

recent account of Schwitzgebel's views is

contained in Ralph Kirkland Gable. "Application of Personal Telemonitoring to Current Problems In Corrections," Journa/ of

Crimina/Justice, 1<4(2), (1986), pp.167-176.

'Information in this section comes from an article, "Electronic Monitor Turns Home Into Jail,"

The New York Times, (February 2, 19&4).

r.Th• e.·.'.• >•.:. .• :. . .•. • .•. .. r.e.

. s

th

. United States imprisoned people far::;2:",cost.i-."';· ...

" . :;"l::'~~1

too long, he argued, and imprison-:;,:.);:~,::· .•. In Apr,i1' 1983.' Judge J.ac.k love.'. Of . ·.:.:.:;..~~.:.'

ment was of no humanitarian and <:..-OC:::···.. the State District Court in Albuquer;;~~

dubious therapeutiC value.

'" ". . .. que, New Mexico, sentenced fourmi-:'2~

.. '. "Recent developments in elec-';

nor offenders to wear small elec:-::":::1\"""

. tronic technology," Schwitzgebel'.,

tronic transmitting devices instead.9

noted in mid· I968, "greatly increase'

going to jail ()r payingafine.Judg~t:r~

the possibility of deterring the com- • Love,felt<thatthe;:rnorito'[swould'

mission of certain types of offenses in, .'.• low(>rO,~tiorl 0fficers~c:i·~eep,t~c.,:

the community. When specific,of- ;,;.,,~;,;oL~;of(,I1d~'~er~by assur:ir,'l8

~en~ingbehaviors can be prevente~~~~H'i;;,:,," 'gp'(I'~'~;con:lI;il~JU~~:

It will no longer be necessary tO~:'.~~$R':.t;;:y;01_..

el.ove also was hesitant.

imprison an offender in order to'" ;' '~''',;a®'L'minor,:()ffendersand feltf

protect the community,'"

·;··:·:;'.:"".·m;:'th;j,~n.. ..deVices could help alleviate'

Schwitzgebel recognized, howevenJ;'tiail 'C~() .:ding/.'

. '.

that civil liberties and ~ther concerns .,.. Judge Love's experiment was genwere of great importance. In fact. he

erally accepted in Albuquerque, and it

argued that "effective administrative .'

received considerable 'local and na.

safeguards" should be developed be·

tional media coverage. But it also received some criticism. Judge William

fore electronic devices were widely

used in public, Monitoring, he sug·

Short, who presided over Albuquer•.

gested, might require joint approval

que's Metropolitan Court, told a

by criminal justice release agencies

reporter that the devices could be

applicable in some situations but

and independent civil liberties groups

or be permitted only when the proc·

shouldn't be used as an alternative to

ess of using these devices could show

jail. "If a person's crime and record.

"long-term therapeutic benefits."

are such that he should get probation," the judge said, "then he should

have an honest chance to prove to

'Ralph K. Schwitzgebel. "Electronic Altersociety that he can behave on his

natives to Imprisonment," Lex et Scientia,

own. If he deserves jail. he should go

5(3). Ouly-September 1968), p. 99. A more

to jail,"l.

'

FALL 1989

7

-<ontinued (rom previous page

Because electronic monitoring is generally used on a catch-as-catch-can basis.

there is little sense of how this method

of responding to criminal offenders affects the way we respond to criminal offending in general.

A recent British experiment. however. suggests that electronic monitoring

could potentially affect the way sentencers align criminal penalties. The experiment attempted to assess how the use

of electronic monitoring could .affect the

proportional use of imprisonment.

Electronic monitoring is

generally used on a catch-ascatch-can basis.

Participants in the study indicated that

electronic monitoring was more appropriate for accused offenders awaiting

trial than as a sentencing option and that

the use of electronic "tagging" would affect the comparative use of other sanctioning options. Specifically, the study

suggested that the use ~f fines (more

commonly used in the U.K.) would increase as a replacement for both probation and imprisonment when electronic

tagging was also used. Moreover, the

study found that such monitoring would

generally be used as an intermediate option between "lenient" release and "restrictive" incarceration. 9

The whole business of a hierarchy of

penalties is probably more widely accepted within the British context, however. The British concept of a sentencing

tariff. the development of a proportional

and escalating range of penalties. is

largely unknown in this country. The

American concept of a "going rate" for

criminal penalties based on local legal

culture emerges informally and rather

conveniently within a larger court and

legislative context undefined by conscious sentencing policy.

In the United States. the phrase "intermediate sanction" or "intermediate

punishments" will likely gain further currency in the next few years. IO However,

'Sally M. Frost and Geoffrey M. Stephenson. "A

Simulation Study of Electronic Monitoring as a Sentencing Option," The Howard Jaurnal. 28(2), (May

1989). pp.91-104.

,oMichael H. Tonry and Richard Will have written

a monograph. Intermediate Sanctions, which will be

published shortly by the National Institute of Justice. In addition, Tonry, who has written extensively about sentencing reform, has teamed up

with NorvaJ Morris of the University of Chicago

Law School to write a.book, Between Prison and

Probation: Intermediate Punishments in a Rational

Sentencing System, which will be published by Oxford University Press in January 1990.

8

FALL 1989

Policymakers are still unsure: will electronic monitoring alleviate prison overcrowding or widen the

net o( social control?

intermediate sanctions. like the original

were clearly centered on intensifying ofpresumptive sentencing proposals made

ficial supervision of defendants and ofin the late 1970s, are undoubtedly subfenders. not displacing these people

ject to the same sort of misapplication

from imprisonment. More recent applithat effectively co-opted and abated

cations of electronic monitoring, howmost attempts at implementing the guide. ever. are stressing decarceration. Oklaing principles of this earlier effort to rehoma, for instance, is now using

form sentencing practices.

monitoring devices to supervise persons

Presumptive sentencing, as originally

who are released from prison early beproposed, promised to shorten terms of cause of overcrowding.

imprisonment as well as reduce disparity

More to t~e point. Edmund B.

among imposed sentences. In general,

Wutzer, director of the New York

longer sentences resulted. Significantly.

State Division of Probation and Correcearly proponents of intermediate sanctional Alternatives. recently told a legislatively-sponsored public hearing on the

tions are far from knee-jerk supporters

role of electronic monitoring in the

of innovations such as electronic

monitoring.

.criminal justice system that "electronically monitored house arrest should be

utilized exclusively as a post-dispositional

Conclusion

alternative to incarceration and its appli"At present," Michael Tonry and

cation should be restricted to felony ofRichard Will wrote in a report for the

fenders for whom no other alternative.

National Institute of Justice, "electronic

or combination of alternatives. would

suffice to divert the individual from

monitoring is too often used in house

arrest and intensive supervision probaconfinement."

tion programs to monitor persons conFurthermore. Wutzer observed that

"our perspective that electronic monivicted of minor crimes and who present

few meaningful risks to public safety. For toring be employed as an alternative of

last resort is founded largely on the consuch offenders. electronic monitoring is

an expensive redundancy whose justifica- cept that electronically monitored home

tions must be political and public relaconfinement must be implemented in a

tions and not prophylactic.""

manner consistent with proportionality

Early electronic monitoring programs

in sentencing and in a way that does not

denigrate the value of other. already operational alternatives. If this new sanc"Michael Tonry and Richard Will, Intermediate

tion is imposed in cases where other alSanctions, (Castine. ME: unpublished report preternatives are now or could be applied.

pared for the National Institute of Justice), (1988).

p.19.

-continued on page sixteen

)

)

)

HIGHLIGHTS OF MOST

IMPORTANT CASES

Remedies-Closing of Facilities/Pretrial

Detainees/Contemptffotality of

Conditions/Crowding

Despite doctrines of deference to prison authorities, federal courts remain willing to use

their wide-ranging equitable powers to ensure

minimallv decent conditions of confinement. In

Inmates ofAllegheny County v. Wecht, 874 F.2d

147 (3rd Cir. 1989), the Court of Appeals upheld an order that the jail be closed. Although

conditions had improved since the beginning of

the 13-year-old litigation, the district court had

concluded that its prior orders had been "ineffective" to ensure constitutional conditions and

that "more stringent remedies" were required,

adding, "As a jail, time has passed this building

by." 699 F.Supp. 1137,1146-48 (W.O. Pa. 1988).

On appeal, the court held that the order was to

be reviewed by the usual abuse of discretion

standard as long as the record supported the

finding of constitutional violations. It added

(at 153): "When the totality of conditions in a

jail violates the Constitution a district court need

not confme itself to the elimination of specific

conditions.... Rather, the nature of the overall

violation determines the permissible scope of an

effective remedy.... Aremedy cannot, however,

go beyond the constitutional violations found."

[Citations omitted.) The court also upheld contempt fines for violations of population caps and

mental health stalfmg requirements, holding that

the impossibility defense to contempt refers to

"physical impossibility beyond the control of the

alleged contemnor." That standard was not met

here because the orders were directed to all the

defendants, including county officials, who "simply chose to take no steps to provide the Warden and his staff with the wherewithal to comply." (152)

In an even longer-running case, Palmigiano v.

DiPrete, 710 F.Supp. 875 (D.RI. 1989), the district court held that the Governor and the director of the Department of Corrections had failed

to purge themselves of contempt by complying

with prior orders, including population limits,

governing detention conditions. Their long-term

proposals were not responsive to the court's demand for immediate population reductions to

remedy long·standing violations of those orders.

The court held that the state executive branch

may be held accountable for implementing court

orders regarding state prison conditiOns, brushing aside their arguments that they lack "plenary

power to appropriate funds or enact legislation

..." (n.14). It gave equally short shrift to their

"unforeseen circumstances" argument, which it

said "shocks the sensibilities of this Court" in

view of the long history of overcrowding and

failure to address it. "This Court simply fails to

grasp the logic by which a problem recognized

for years is rendered unanticipated because it

has worsened." (884)

The court proceeded to levy the fines set prospectively in its previous order of 550 a day per

person held over the population cap. At 887: "A

federal court may, in the exercise of its eqUitable

power, order that fines it has imposed as sanctions for civil contempt be used to remedy the

problem underlying the contempt finding....

Even more to the point, federal courts faced

with prison overcrowding of crisis proportions

have exercised their equitable powers to order

that fines collected as contempt sanctions be

used to pay the bail of indigent detainees,

thereby effecting an immediate reduction in the

population." The court therefore ordered that

5164,250 of the accrued 5289,000 in fines b~

used as a bail fund. The remaining fines were

suspended, to be levied if full compliance is not

obtained. (Ed. note: The Court of Appeals af·

firmed this decision on August 17, 1989, C.A.

No. 89-1440.)

Procedural Due Process-Administrative

Segregation

ACalifornia federal court has set a constitu·

tional standard for the frequency of periodic review of placement in administrative segregation.

In Toussaint v. Rowland, 711 F.Supp. 536 (N.D.

Cal. 1989), the court held that the necessity for

continued segregation must be reassessed every

90 days and that a 120-day delay between reviews denies due process. This decision appears

to be the first to set a firm constitutional standard on the question. Previous decisions had upheld periods ranging from a month to 90 days

without expressly disapproving any interval

much shorter than a year. See MCQueen L'. Tabah, 839 F.2d 1525, 1529 (11th Cir. 1988)

(eleven months without review stated a due process claim); Tyler v. Black, 811 F.2d 424, 429

(8th Cir. 1987) (90 days "approaches constitutionallimits"); Toussaint v. JfcCarthy, 801 F.2d

1080, 1101 (9th Cir. 1986) (twelve months

without review denied due process); Clark v.

Brewer, 776 F.2d 226, 234 (8th Cir. 1985)

(weekly hearings for two months and monthly

hearings thereafter upheld); .'rfims v. Shapp, 744

F.2d 946, 952-54 (3rd Cir. 1984) (30-day review

adequate). The court made additional rulings

concerning due process in administrative segregation discussed .below.

The defendants have appealed, but no decision

is expected until well into 1990.

Religion

Recent federal appellate decisions on prisoners' religious rights reveal deep divisions in

the application of the Supreme Court's decision

in O'Lone v. Shabazz. The SLxth Circuit, in Whitney v. Brown, 882 F.2d 1068 (6th Cir. 1989),

struck down as unconstitutional a de facto prohibition on congregate Passover Seders and on

Sabbath services that resulted from newly imposed movement restrictiOns in a Michigan

prison.

The Whitney court held that the Passover

Seder claim "may easily and significantly be distinguished from O'Lone" because it involved six

inmates and a ceremony that takes a few hours

once a year, as opposed to the larger number of

Muslim inmates in O'Lone who wished to be released from work for Jumu'ah services every Friday. Regarding the Sabbath service claim, on

which the district court had ruled for prison officials, the court considered and directly rejected

A PROJECT OF THE

.\..\IERIC....' i Cl\1L LIBERTIES CSIOS

FOI:SDATION. ISe.

Since September of 1984, attorneYs andO;t'm

other criminal justice practitioners have ,.' ,:"j

turned to the National Prison ProjectjOUR:li

NAL for timely, comprehensive, and accuratei

coverage of prison issues.

.. .

...,k~l

ThejOURNAL covers the latest news on.2~~

AIDS in prison, overcrowding and its effeets;;;~

corrections litigation, and much more. We:;:';j

cover topics in depth and with an analysis':';J1

that you simply will not find eIsewhere:,;i;i~

With this issue we are happy to introd!lS~J

far::~;::~eat~{~:'::,1;:ce:::;;;ri~:J

federal court opinions wqich are relevant' t.9~~

corrections litigation. Each opinion is indet~

to. ?ne..or more ~bject ~atter. headnotes;.an

. ,.,. <'..$1

penodlcally we will publIsh a compIete-<·/;~Y~

index.

".. ·,/~'t~

Case Law Report is prepar~d by J~~BoSI~

ton, a staff attorney at the Prisoners Rights;f~

Project, Legal Aid Society of New York. A.··.· ,1f'j

graduate of New York University Law SChoO~'i

Boston has co-authored Counsel for fbi PoOti'l

Criminal Defense in Urban America, and ed;:;l

ited the revised second edition of the Pris-,;;}{

oners'SelfHelp Litigation Manual. '<:r~~

Boston, who has been involved in pris-t<.dJ

oners' rights litigation since the early 1970s,!~

is "a lawyer's lawyer," according to Ed Komij

of the Nation:l;l Prison Project He is well>;

known as someone to whom experienced ..;:

lawyers will go for information and advice.

We guarantee that his concise, authoritative

reports on recent court' decisions will become an indispensable source of important

new legal developments for you and your

colleagues.

prison officials' security arguments. They had asserted that the Jewish inmates were in danger of

attack and there was potential for escape or the

smuggling of contraband. However, the court

noted that there was no evidence in the record

of escape attempts or of any unusual vulnerabilitv of these inmates to attack. and that inmates

found with contraband had been disciplined individually. Since there was much movement of

inmates from complex to complex for other purposes, the court termed it "inconsistent and irrational" to prohibit a few inmates to travel to Sabbath services, and also stressed the "glaring

inconsistency" of the defendants' practice of letting prisoners in the ma.ximum security complex

FALL 1989

9

assemble a minyan by having an outside rabbi

bring in civilian volunteers while prohibiting attendance by prisoners from other complexes.

More generally, the court stated (at 1074):

"Perhaps the greatest weakness in the prison officials' arguments is their misunderstanding of

Turner and O'Lone as holding that federal courts

will uphold prison policies which can somehow

be supported with a flurry of disconnected and

self-conflicting points. They seem to read Turner

and O'Lone as saying that anything prison officials can justify is valid because they have somehow justified it. In an argument typical of their

conclusory approach to the problem, the prison

officials maintain that the Passover Seders should

be banned because '[alny time the normal rou·

tine of an institution is altered, the good order

and security of that facility are potentially compromised.' ... The fact remains, however, that

prison officials do not set constirutional stan·

dards by fiat."

The Second Circuit took a very different ana·

Iytical approach in Fromer v. Scully, 874 F.2d 69

(2d Cir. 1989), which upheld a rule limiting

beards to one inch in length as applied to an Or·

thodox Jewish prisoner. The court stated, "We

believe that Turner and O'Lone call for greater

deference to the judgment of prison officials

than was given by the district court." (73)

The district court had held that it was "not

persuaded" of the logical connection between

the prison officials' concern for identification

and the beard rule; the appellate court stated

that there was no burden of persuasion on the

defendants. The Circuit also rejected the plain'

tiffs' arguments concerning inconsistencies in the

prison officials' security arguments. The plaintiff

had argued that the rule was irrational because

only a complete prohibition on beards would

serve the defendants' interest in identification;

the court "reject[edl that approach as leading to

perverse incentives for prison officials not to

compromise with inmate desires lest all future

demands be compared with the compromise

rather than with minimal constitutional require·

ments." (74) The court also rejected the argument that defendants' concern about contraband

hidden in beards was irrational as long as pris·

oners could hide contraband in their clothing,

and was unmoved by the fact that the defendants

produced no evidence of contrab~d found in

beards, holding that it could not "second-guess

reasonable efforts" at anticipating future security

problems. (75) It held that the plaintiff had alter·

native means of religious observance, such as

obeying dietary laws. It disapproved the district

court's unsupported assumption that there are

few Orthodox Jews in state prisons, holding that

the defendants had no burden to produce evidence on that point. Finally, it found that the alternative of periodically rephotographing inmates who grow beards had more than de

minimis costs, financially and administratively.

Ironically, the Fromer court relied in part on

the Sixth Circuit's prior decision in Pollock v.

Jlarshall, 845 F.2d 6;6 (6th Cir. 1988), in

which short shrift was given to a Native American prisoner's religious objection to haircutting.

Other post·O'Lone Circuit decisions addressing

religious rights in the context of a factual record

include: McCorkle v.johnson, 881 F.2d 993

(ll th Cir. 1989) (restrictions on Satanic literature upheld); Siddiqi v. Leak, 880 F.2d 904 (7th

10

FAll 1989

Cir. 1989) (screening mechanism for outside religious organizations upheld);]ohnson·Bty v.

Lane, 863 F.2d 1308, 1312 (7th Cir. 1988) (in'

mate-led religious services could be prohibited);

SapaNajin v. Gunter, 857 F.2d 463 (8th Cir.

1988) (Sioux prisoner's rights were violated

where only available medicine man was a member of a sect of "institutionalized deviants"; de·

fendants required to provide some services by

other medicine men); Cooper v. Tard, 855 F.2d

125 (3rd Cir. 1988) (ban on unsupervised group

prayer in high-security unit upheld); Williams v.

Lane, 851 F.2d 867, 877-78 (7th Cir. 1988)

(denial of group worship and other religious

rights to protective custody inmates was unconstitutional); Reed v. Faulkner, 842 F.2d 960 (7th

Cir. 1988) ("conjecture" concerning violence

resulting from wearing of dreadlocks did not

justify ban; plaintiffs' evidence of arbitrary enforcement of the ban shifted the burden of justi·

fication to the defendants); Kahty v.jones, 836

F.2d 948 (5th Cir. 1988) (prison officials need

not accommodate plaintiJfs request for an indivi·

dualized religious diet).

were inadequately trained in the use of "canine

force" based on evidence "that police dogs must

be subject to continual, rigorous training in Jaw

enforcement techniques," that officers "resorted

to the use of canine force more frequently than

did canine units in other municipalities," that the

city's ratio of bites to apprehensions was viewed

as an indicator of an "irresponsible use of force,"

and that canine officers "often used excessive

force to apprehend individuals suspected only of

minor misdemeanor offenses." (1556)

Ajury could have concluded that this inadequate training reflected city policy because can·

ine force frequently resulted in injury to the sus·

pect, force reports were fJ..led in each such case,

these reports were "then reviewed by supervisory officials - inclllding the municipality's former chief of police-to whom the City had delegated policyrnaking authority."

The court also held that the exclusion of evi·

dence of pending lawsuits alleging excessive

force was "almost certainly erroneous" since

these were relevant to the question of the City's

notice of the unconstitutional conduct.

Communication and Expression

The federal courts continue to defend a pris·

oner's right to criticize his keepers. In Meriwether v. Coughlin, 879 F.2d 1037 (2d Cir.

1989), damages were a1flIllled for inmates who

were transferred for complaining publicly about

alleged mismanagement and corruption and airing their grievances at a meeting with the Superintendent. The court stated, "Prison officials have

broad discretion to transfer prisOners ... They

may not, however, transfer them solely in retaliation for the exercise of constitutional rights."

879 F.2d at 1046. The jUry rejected the officials'

claim that the transferred inmates had been in·

volved in planning an insurrection. The prisoners

also received damages for assaults by guards in

the course of their transfers.

This post· Thornburgh v. Abbott decision is

. consistent with the approach of numerous recent pre·Abbott decisions in First Amendment

retaliation cases. See Todaro v. Bowman, 872

F.2d 43 (3rd Cie. 1989) (discipline for letters

complaining about jail); Cale v.johnson, 861

F.2d 943 (6th Cir. 1988) (discipline for complaints about food); see also Frazier v. King, 873

F.2d 820 (5th Cie. 1989) (nurse's disclosure of

prison nursing standards violations was protected expression). Complaints made through of·

ficial grievance processes are particularly worthy

of protection. See Sprouse v. Babcock, 870 F.2d

450,452 (8th Cie. 1989) (analogizing grievances

to lawsuits);]ackson v. Cain, 864 F.2d 1235,

1248-49 (5th Cir. 1989); Wildberger v. Bracknell, 869 F.2d 1467 (lIth Cir. 1989); but see

Williams v. Smith, 717 F.supp. 523 (W.O. Mich.

1989) (retaliatory disciplinary charge of which

the prisoner was cleared did.not violate substan·

tive due process).

Municipalitiesffraining

In an important early application of the Can·

ton v. Harris standards for municipalliabiIity,

the Eleventh Circuit has upheld a jury verdict

against a city based on inadequate police train·

ing. In Kerr v. City of West Palm Beach, 875

F.2d 1546 (lIth Cie. 1989), the court held that

a jury could have concluded that police officers

OTHER CASES WORTH

NOTING

U.S. COURT OF APPEAlS

Attomeys' Fees and Costs/fransportation to

CourtslIn Forma Pauperis

Sales v. Marshall, 873 F.2d 115 (6th Cir. 1989).

Writs of habeas corpus ad testificandum are generally issued under the habeas corpus statutes and not

the All Writs Act, and there is no authority for imposing the costs of transportation to court on a prisoner·plaintiff. (But these costs may be awarded

against the plaintiff for transportation of prisoner

witnesses.) Expenses of the defendants' deposition

of the plaintiff may be taxed as costs against the in

forma pauperis plaintiff, subject to a determination

that the plaintiff is able to pay the costs.

When a prison is reqUired to produce an inmate

for proceedings in which the prison is not a party

(here, a state prisoner's suit based on events in the

county jail), the prison may not seek transportation

costs without having timely intervened.

Habeas Corpus

Sheppard v. State of La. Board ofParole, 873

F.2d 761 (5th Cie. 1989). The plaintift's parole was

revoked because he failed to pay 543 a month in pa·

role supervision fees. His challenge to the constitu·

tionality of the fee statute's application to him was

barred by Preiser v. Rodriguez, even though he

sought damages and a declaration and not release.

because if he were successful the basis for his incarceration would be undermined

In Forma Pauperis

In re Funkhouser, 873 F.2d 1076 (8th Cir. 1989).

If a prisoner is required to pay a partial filing fee.

the court should treat the case in the same manner

as one not filed in forma pauperis. There should be

no further proceedings concerning whether the

complaint is frivolous; this determination should be

made before a partial ruing fee is reqUired. The

court of appeals chastises the magistrate ("We deem

it extraordinary ...") for a 17-month delay in determining the plaintiffs' eligibility for IFP status, in a

case involVing serious constitutional claims in which

the pro se plaintiffs had rued a motion for a prelimi·

nary injunction. The magistrate is directed to con·

suit with the chief judge "to adopt procedures

which would ensure immediate processing of all

motions of prisoners to proceed in forma pauperis

in a reasonable and timely manner."

Discovery

Greenberg v. Hilton International Co., 875 F.2d

39 (2d Cir. 1989). At 42: "In the future, requests for

costly statistical compilation useful only for profes·

sional analysis should be accompanied by reasonably

precise representations as to counsel's intentions

with regard to preliminary analysis and to retention

of an expert. Those resisting such discovery can

then be given the option of producing only that

data necessary to preliminary analysis with more

elaborate production to follow if the preliminary

analysis indicates that more sophisticated examina·

tion would be useful."

Procedural Due Process-;-Disciplinary

ProceedingslHabeas CorpuslFederal Officials

and Prisons

Greene v. Meese, 875 F.2d 639 (7th Cir. 1989).

The plaintiff, a federal prisoner, alleged that he had

been subjected to repeated disciplinary sanctions in

retaliation for rejecting guards' homosexual solicita·

tions and resisting searches that had "homosexual

overtones," and sought damages, restoration of good

time and parole eligibility.

Because the relief sought by the plaintiff would

shorten his confinement, he was required to exhaust

his administrative remedies with respect to each dis·

ciplinary conviction he challenged, even if it was

likely that he would lose.

The fact that the plaintiff also sought damages did

not alter this result. At 642: "A prisoner may not cir·

cumvent the requirement ofcomplete exhaustion

by first suing for damages or a declaratory judgment

and then using a favorable judgment in that suit as a

basis for requesting a reduction in the length of his

imprisonment."

Remedies/Attorneys' Fees and Costs

Muckleshoot Tribe v. Puget Sound Power <S:

Light Co., 875 F.2d 695 (9th Cir. 1989). For a set·

tlement to waive attorneys' fees, the waiver must

appear in the settlement and must "clearly accomplish" that purpose. It is not necessary for the plain·

tiff to reserve the fees question. If poor draftsman·

ship frustrates that purpose, the defendant may

resort to extrinsic evidence and prevail "if it can

show clearly that the parties mutually intended" a

fee waiver. (698) Dismissal of the complaint with

prejudice does not serve as a fee waiver.

Statutes of LimitationslMunicipalities/

Staffing-Training

Jferritt v. County ofLos A.ngeles. 875 F.2d 765

(9th Cir. 1989). 'Xbere the plaintiff in a police misconduct case sued the city within the limitations pe·

riod but onlY identified the individual officers after

the statute had run, state law ':John Doe" tolling

rules which did not require notice to the officers

during the limitations period should have been

applied.

The evidence did not support municipal liability

for inadequate use of force training. "Each prospec'

tive deputy is given, prior to his academy training. a

two-day training session regarding the department's

policies on the use of force. TWellty percent of the

academy training, which may last from four to six

months, addresses the use of force. Some ten percent of specialized post-academy training continues

the deputy's education regarding use of force."

(770) The omission to train regarding a "very rare"

situation does not amount to deliberate indifference.

Personallntegrity/Clothing

Felts v. Estel/e, 875 F.2d 785 (9th Cir. 1989).

Where a jailed criminal defendant was not prOVided

with civilian clothes until sLx days into his trial, due

process was denied. At 786: "[T]he state is under an

affirmative duty to provide civilian clothing in a

timely fashion and, if no such clothing is in its possession, to prOVide reasonable funds for the pur·

chase of acceptable attire." The court reserves the

question of what constitutes "suitable clothing" and

whether the answer is different if the defendant is

representing himself.

Medical Care/Suicide Prevention!Qualified

Immunity

Danese v. Asman, 875 F.2d 1239 (6th Cir. 1989).

Jail officials were entitled to qualified immunity in a

jail suicide case. Although the rights to be free of

deliberate indifference to medical needs and of un·

justified intrusions on personal security were clearly

established, these are not "particularized" enough to

put the defendants on notice of their obligations on

these facts. At 1244: "The 'right' that is truly at issue

here is the right of a detainee to be screened cor·

rectly for suicidal tendencies and the right to have

steps taken that would have prevented suicide."

This is different from medical care cases involVing

deliberate indifference to prisoners who request

care.

Prior case law "only establishes the general prin·

ciple that supervisors are liable for grossly negligent

or nonexistent training that leads to the violation of

constitutional rights; It does not say that suicide

procedures and training must be provided." (1245)

Management, Safety and SecuritylUse of

ForcelPersonallnvolvement and Supervisory

LiabilitylDamageslEmergency

Bolin v. Black, 875 F.2d 1343 (8th Cir. 1989).

After a disturbance in which an officer was stabbed

to death, officers engaged in retaliatory beatings.

The assistant corrections director could be held

liable based on testimony that placed him in clear

view of the beatings and the fact that he took no action. The facts establish both deliberate indifference

and tacit authorization, either of which is sufficient

to support liability.

The associate warden could be held liable based

on evidence that he "knew or should have known