Journal 3

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

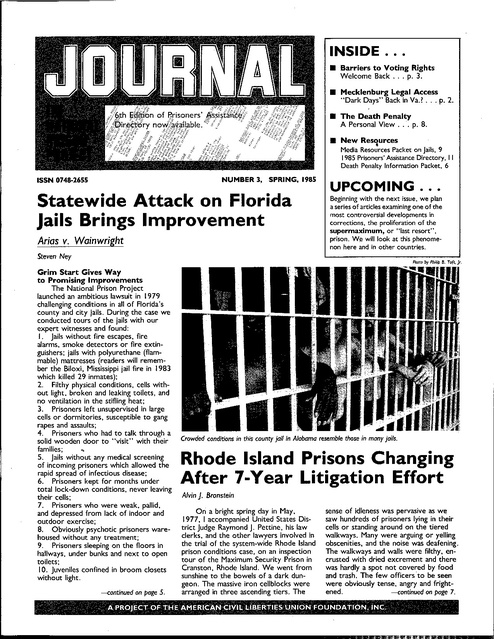

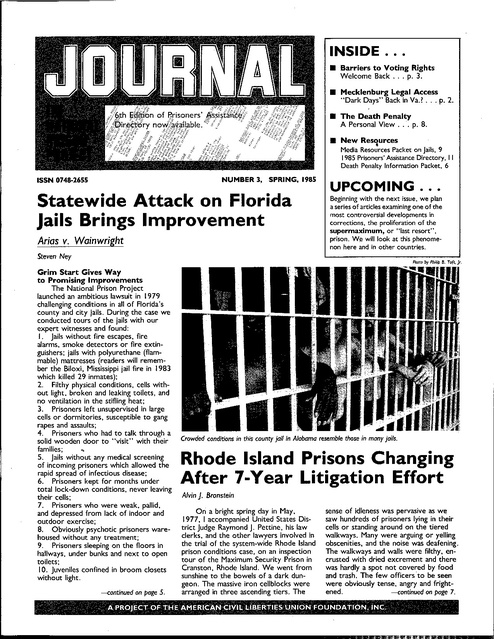

INSIDE ... • Barriers to Voting Rights Welcome Back ... p. 3. • Mecklenburg Legal Access "Dark Days" Back in Va.? ... p. 2. • The Death Penalty A Personal View .... p. 8. • NUMBER 3, ISSN 0748·2655 SPRING,1985 Statewide Attack on Florida Jails Brings Improvement Arias v. Wainwright New Res~urces Media Resources Packet on Jails, 9 1985 Prisoners' Assistance Directory. II Death Penalty Information Packet. 6 UPCOMING ... Beginning with the next issue, we plan a series of articles examining one of the most controversial developments in corrections. the proliferation of the supermaximum, or "last resort", prison. We will look at this phenomenon here and in other countries. Steven Ney Grim Start Gives Way to Promising Improvements The National Prison Project launched an ambitious lawsuit in 1979 challenging conditions in all of Florida's county and city jails. During the case we conducted tours of the jails with our expert witnesses and found: I. jails without fire escapes, fire alarms, smoke detectors or fire extingUishers; jails with polyurethane (flammable) mattresses (readers will remember the Biloxi, Mississippi jail fire in 1983 which killed 29 inmates); 2. Filthy physical conditions, cells without light, broken and leaking toilets, and no ventilation in the stifling heat; 3. Prisoners left unsupervised in large cells or dormitories, susceptible to gang rapes and assaults; 4. Prisoners who had to talk through a solid wooden door to "visit" with their families; " 5. Jails without any medical screening of incoming prisoners which allowed the rapid spread of infectious disease; 6. Prisoners kept for months under total lock-down conditions, never leaving their cells; 7. Prisoners who were weak, pallid, and depressed from lack of indoor and outdoor exercise; 8. Obviously psychotic prisoners warehoused without any treatment; 9. Prisoners sleeping on the floors in hallways, under bunks and next to open toilets; 10. juveniles confined in broom closets without light. -continued on page 5. Crowded conditions in this county jail in Alabama resemble those in many jails. Rhode Island Prisons Changing After 7-Year Litigation Effort Alvin j. Bronstein Ori a bright spring day in May, 1977, I accompanied United States District judge Raymond j. Pettine, his law clerks, and the other lawyers involved in the trial of the system-wide Rhode Island prison conditions case, on an inspection tour of the Maximum Security Prison in Cranston, Rhode Island. We went from sunshine to the bowels of a dark dungeon. The massive iron cellblocks were arranged in three ascending tiers. The sense of idleness was pervasive as we saw hundreds of prisoners lying in their cells or standing around on the tiered walkways. Many were arguing or yelling obscenities, and the noise was deafening. The walkways and walls were filthy, encrusted with dried excrement and there was hardly a spot not covered by food and trash. The few officers to be seen were obViously tense, angry and frightened. -continued on page 7. A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL.. I...IBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, INC. Judge Halts Meddling With Access to Clients Elizabeth Alexander Judge Robert R. Merhige, Jr., of the federal district court in Richmond, Virginia sharply reprimanded officials of the troubled Mecklenburg Correctional Center in the course of granting the National Prison Project a preliminary injunction. The injunction ordered a stop to practices at the super-maximum security institution that the judge found violated Mecklenburg inmates' constitutionally protected right of access to the courts. Since Mecklenburg's opening in 1977, the prison has been controversial. rectional officers were fired and another disciplined for abuse of inmates during a shakedown. In another incident, in part triggered by the July 26 events, inmates took nine employees hostage. The prison administration's reaction to the unrest at the prison included a decision to restrict lawyer access to in- mates. After the new policies were implemented, most inmates seen by the Prison Project staff had their hands shackled to their waists during interviews. Guards required the interview to be conducted with the doors to the interviewing room open. New policies limited the hours available for interviews and the length of time for individual interviews. In addition, for all practical purposes, only one contact lawyer-client interview could take place at a time, As a result of these new policies, lawyers and paralegals from our office who attempted~to interview Mecklenburg clients found that the eight-hour .round trip from Washington to the prison produced, on the average, only two Photo courtesy of Richmond Newspapers. Inc. Following the hearing, Judge Merhige decided that the Prison Project lawyers had shown by "conclusive evidence" that the new policies were an exaggerated response by the Mecklenburg officials to their security concerns at the prison. Opponents, including the Prison Project, charged that its Phase Program for troublesome inmates was an ill-conceived travesty of behavioral modification principles. Critics predicted that the program would ultimately backfire because the behavior of inmates assigned to the institution would deteriorate. Concern about the Mecklenburg program grew as persistent complaints of guard brutality circulated. In 1981 we filed suit against Mecklenburg and in April of 1983, after extensive trial preparation, we signed a settlement agreement with the Virginia Department of Corrections. The agreement was designed to make major changes in the prison's operations. By the spring of 1984, the lawyers on the case, Elizabeth Alexander, Alvin J. Bronstein, and local counsel Gerald Zerkin, were preparing to return to court, charging that the settlement agreement had never been implemented. Unfortunately, in May of 1984, six Death Row prisoners escaped from Mecklenburg, adding to the prison's considerable notoriety. During the summer of 1984, the prison remained on lockdown and was exceptionally tense. There were a number of incidents in which force was used on prisoners. Following one incident on July 26, two cor2 SPRING 1985 Mecklenburg Correctional Center in Boydton, Virginia. The National Prison Project of the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation 1346 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. JAN ELVIN Editor, NPP JOURNAL Washington, D.C. 20036 (202) 331-0500 ALVIN j. BRONSTEIN Executive Director STEVEN NEY Chief Staff Counsel EDWARD I. KOREN MARY E. McCLYMONT URVASHI VAID CLAUDIA WRIGHT SHARON R. GORETSKY Administrative Director and Research Associate BERYL JONES DAN MANVILLE Research Associate LYNTHIA SIMONETTE STAFF ATTORNEYS ADjOA A. AIYETORO ELIZABETH R. ALEXANDER SUPPORT STAFF BETSY BERNAT Editorial Assistant MELVIN GIBBONS The National Prison Project is a tax-exempt foundation-funded project of the ACLU Foundation which seeks to strengthen and protect the rights of adult and juvenile offenders; to improve overall conditions in correctional facilities by using existing administrative, legislative and judicial channels; and to develop alternatives to incarceration. The reprinting of JOURNAL material is encouraged with the stipulation that the National Prison Project JOURNAL be credited with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint be sent to the editor. The JOURNAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by the National Prison Project. Materials and suggestions are welcome. The National Prison Project JOURNAL is designed by james True. ..-----------~._---_ .. _- hours per day of actual visiting time with inmate clients. Because of the new policies, we were hindered in preparing our motion for contempt against the Mecklenburg officials for violation of the consent decree. We filed a motion for a preliminary injunction to halt the new policies. This motion was heard by judge Merhige in a full-day hearing on September 27. Following the hearing, judge Merhige decided that the Prison Project lawyers had shown by "conclusive evidence" that the new policies were an exaggerated response by the Mecklenburg officials to their security concerns at the prison. Indeed, judge Merhige found that security concerns were not the Mecklenburg officials' primary reason for imposing the new policies. Rather, a major reason for the new policies was "a perceived public relations gimmick-an attempt to find a scapegoat of some kind" for Mecklenburg's summer of troubles. judge Merhige referred to the very early prison case of Landman v. Royster, in which he had found Virginia officials in contempt of court for failing to stop Judge Merhige remarked from the bench that "the days of Landman v. Royster ... are dark days in the history of the Virginia Penal System, and I thought they were all over. I am not so sure now." ! I I practices he had enjoined at the Virginia State Penitentiary. judge Merhige remarked from the bench that "the days of Landman v. Royster . . . are dark days in the history of the Virginia Penal System, and I thought they were all over. I am not so sure now." judge Merhige then granted a preliminary injunction that gave our clients virtually all the relief sought in the motion. The injunction requires that Mecklenburg allow each lawyer 5 V2 hours of actual inmate interviewing time per day. The 90-minute.limit on individual interviews was struck down, as was the limit to one contact visit at a time. The order also required that client interviews take place in a manner assuring confidentiality, and limited the circumstances under which an inmate could be shackled during a legal interview. With the granting of the preliminary injunction. we have been able to proceed in our efforts to prove that Mecklenburg remains in violation of the settlement agreement. At the beginning of December. we filed a motion for contempt, and a hearing on that motion is tentatively set for hearing this spring. • Ex-Offenders Find Doors Closed On Voting Rights Judy Goldberg Nadine Marsh One of the unexpected results of a felony conviction in the United States is the loss of a freedom most of us consider fundamental to participation in a democratic society-the right to vote. Every state except Massachusetts. Vermont, and Utah disfranchises persons upon conviction of certain crimes. Because of a confusing patchwork of state laws. many ex-offenders find it difficult, if not impossible, to regain access to the ballot once they are released. This practice is based on state constitutional provisions which remove voting privileges upon conviction for such offenses as felonies. "infamous crimes". treason, or crimes involving moral turpitude. Some states include a shopping list of crimes. For example, the South Carolina Constitution denies the vote to: Persons convicted of burglary, arson, obtaining goods or money under false pretenses, perjury, forgery, robbery, bribery, adultery, bigamy, wifebeating, housebreaking, receiving stolen goods, breach of trust with fraudulent intent, fornication, sodomy, incest, assault with intent to ravish, larceny, murder, rape or crimes against the election laws . . . unless such disqualification shall have been removed by pardon. In 1974 the Supreme Court addressed the question of whether the right to vote was fundamental, and subsequently required that disfranchisement be based on a compelling state interest. In Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974), the Court held that Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment specifically permitted states to deny the vote to felons. This language which refers to "Participation in rebellion or other crime" now provides the constitutional basis for the wholesale removal of the ability to vote for tens of thousands of persons per year. The states' rationale for disfranchisement appears to be based on three concerns: that it will prevent potential voter fraud, that ex-offenders would vote for interests subversive to society, and that they have less interest in the political process than other citizens. These misgivings are based on the assumption that former felons are more likely to misuse the ballot. or that they are less concerned with the government than other segments of society. The premise is that leadership should be deter~ined by people of "sound" moral character; once a person has committed a crime, she or he has lost that character and must forfeit the right to participate in the governing process. The barriers to the ballot erected by many states convey the message that. although free, the ex-offender is not yet a welcome member of society. There are three basic means of rights restoration: I) pardons by Governors, 2) automatic restoration of rights upon release or completion of parole, and 3) a catch-all category of varying practices best referred to as "other." Twenty-six states now have some form of automatic restoration of the right to vote upon release or completion of parole and probation. I The conditions differ with state requirements. Some states. such as Arizona and Louisiana, adjust procedures according to the number of offenses committed by a felon. Eight states wait for a specific period before restoring rights. Six states -Iowa, Maryland, New jersey, New Mexico, Oklahoma and South Carolinaprovide restoration by a form of pardon issued by the Governor. The lack of any clear and reasonable nationwide standard on restoration of rights amounts to a violation of both the right to petition government and the right to equal protection. The remaining states use methods which vary in difficulty for the restoration of rights. These methods often involve evidence of good conduct or petitions presented to Boards of Pardons. -continued on next page. 'Arizona, Arkansas. Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho. Illinois, Indiana. Kansas. Louisiana. Michigan. Minnesota. Montana. Nevada. New York. North Carolina. North Dakota. Ohio. Oregon. Pennsylvania. South Dakota. Washington. West Virginia. Wisconsin. Wyoming. Source: Michele Dolfini, Study of the Process of Restoring Civil Rights to Ex-Felons in the Commonwealth of Virginia. 1984. II 11. . .s.p.R'.N.G.1.9.85_3 _ -continued from previous page. judges, registrars, etc. Two statesRhode Island and Mississippi-still have draconian laws requiring a vote of the legislature. Mississippi's law states: Section 253. The legislature may, by a two-thirds vote of both houses, of all members elected, restore the right of suffrage to any person disqualified by reasons of crime; but the reasons therfor shall be spread upon the journal$, and the vote shall be by yeas and nays. An examination of the procedures used by the Commonwealth of Virginia provides some indication of the scope and difficulty of the restoration problem. Each year Virginia removes voting rights from 750 felons who had formerly been registered to vote. At the same time the state releases roughly 3,000 felons from prisons, and of that number only 200, or 6%, have their rights restored. Virginia's first disfranchising provision, enacted in 1830, barred those convicted of an "infamous offense." The current Constitution disfranchises all persons convicted of felonies unless the 4 SPRING 1985 The barriers to the ballot erected by many states convey the message that, although free, the exoffender is not yet a welcome member of society. Governor restores their right to vote. The restoration process requires that the ex-offender provide: • a list of all convictions, with date, court and sentence; • certified copies of all conviction orders; • certified copies of any term of probation, parole, or order reducing the sentence; • the name and address of last parole officer; • a letter from the parole officer; three letters of reference; • proof that all fines, restitutions and • court costs have been paid. This process is cumbersome and very expensive. The practice of withholding civil rights because of financial obligations negatively affects rehabilita- tion efforts in many ways. It is a heavy, sometimes unbearable burden. Former felons often struggle on the job market to get and maintain low paying jobs. Many of those who had court appointed counsel were declared indigent in order to receive it and it is highly unlikely their financial status improved while they were incarcerated. In addition, many are never notified that they owe court and counsel costs, so their bills increase as interest charges grow. Most unfairly, this repayment prerequisite means those better off will find it easier to get back into the mainstream while the poor and uneducated will have considerably more difficulty regaining citizenship. The process clearly needs reform. Recently the Governor's Commission to Improve Voter Registration in Virginia recommended streamlining the process and taking into account indigency or good faith efforts to repay the debt. It is not known whether these suggestions will be acted upon. The lack of any clear and reasonable nationwide standard on restoration of rights amounts to a violation of both the -continued on page 5. Florida Jails -continued from front page. In late 1981, we obtained a precedent-setting consent decree against the Florida Department of Corrections requiring that the Department take affirmative action to upgrade the conditions in the jails in conformity with state jail standards. In February, 1984, we returned for one of our periodic compliance tours of seven of the jails and were encouraged by the progress in certain counties: • Some counties had installed fire escapes, smoke detectors, fire alarms and other life safety equipment; polyurethane mattresses and padding had been removed; • Staff had been hired in some jails to provide around the clock supervision; • Several jails were screening incoming inmates and providing some ongoing medical care; • Some jails have hired nurses and are keeping medical records and referring prisoners to outside facilities for medical treatment; • Parking lots in some facilities are being converted into outdoor exercise areas so that prisoners are allowed some out of cell time; -continued from page 4. right to petition government and the right to equal protection. Numerous organizations involved in corrections have called for repeal of laws depriving convicted persons of civil rights. Progress has been slow. Between 1978 and 1984 only 4 states were added to the list of those which automatically restore rights upon completion of sentence or parole. Disfranchisement, one of the many severe consequences of conviction for a felony, is an inconsistent, excessive and disproportionate punishment. The blanket imposition of the loss of basic civil rights c1eaf'lly has no legal merit nor does it meet any community need, while it severely hinders efforts by ex-offenders to reconstruct their lives. The complexities in the applications process and the demands it makes on former felons, particularly repayment of debt, are excessive. While to deny former felons their civil rights may provide the public another means of retaliation upon persons who have deviated from the norm, it defeats the positive aims toward which the justice system should strive. • judy Goldberg is the Associate Director of the ACLU of Virginia. Ms. Marsh is an intern in that office. Some jails are utilizing community mental health facilities; • Overcrowding has been reduced in several jails through increased use of release on recognizance and lower bail schedules. This is not to say that Florida's jails are now constitutional, or that they have even entered the twentieth century. The court order is still not being complied with in many respects and we are in the process of filing for supplementary relief. Many of the same barbaric practices continue: prisoners are shackled in leg irons while inside their cells; many juveniles are left unsupervised; visiting is still being conducted through tiny holes in doors; entire floors are left without staff supervision; there is no daily sick call. In one jail we even found the minister doubling as the barber (better than the barber doubling as the doctor!). Nonetheless, Florida seems to be moving in the right direction as a result of our lawsuit. • Statewide Approach Presents Challenge Like most states, Florida has at least one jail in each of its counties-67 at last count, and in addition, it has more than I50 city and municipal lockups. Because the conditions were generally acknowledged to be deplorable, the problem we addressed was how to improve conditions throughout the state without the incredibly expensive and time consuming job of suing each jail separately. While individual jail cases have led to significant improvements in local conditions, given the hundreds of jails in the state and the limited resources at our disposal, we thought that a statewide approach might represent a dramatic breakthrough. The legal stumbling block was to find a way of linking all of the separately run jails into a statewide class action. Unlike a state prison system, which is run by a state level Department of Corrections, the fact that the jails were operated independently by dozens of local governments presented a difficult obstacle to a statewide lawsuit. Fortunately a legal handle was within our grasp. In Miller v. Carson, 563 F.2d 757 (5th Cir. 1977), the Court of Appeals found that Florida Secretary of Corrections, Louis Wainwright, was liable for causing unconstitutional conditions in the Duval County Oacksonville) jail, by virtue of a state law which gave him supervisory responsibility over local jails. That statute made Wainwright responsible for establishing minimum standards for jail conditions, inspecting jails for compliance with the standards, and enforcing the standards by filing suit in state court either to remove prisoners from noncomplying jails or to close the jail. The Court noted that when a state official's violation of state law "causes the imposition of cruel and unusual punishment, a federal cause of action arises under § 1983." The logical sequel to Miller which we developed was Arias v. Wain wright I , a class action against Wainwright alleging that he was responsible for causing constitutional violations throughout the state's jails arising from his failure to carry out the sta~utory obligations outlined above. Prosecuting Arias, Hurdle by Hurdle In prosecuting Arias, we had to overcome a number of legal and factual obstacles. First, we faced the question of class certification. The defendants claimed that there was no typical or common claim to link the plaintiffs and therefore there was no bona fide class. We responded that while it was true that the jails were separately run and that particular conditions varied from jail to jail, there was a common thread which linked all of the inmates and jails, namely the state-run inspection and enforcement scheme. Thus, the claim common to all inmates was Wainwright's alleged failure to carry out his supervisory duties. As it turned out, Wainwright later consented to class certification, apparently for reasons of convenience. Since he was being sued in a number of local jail cases and was seeking to avoid having to appear and defend in different forums, he moved to stay those cases based on his status as a defendant in the statewide case. By certifying our case as a class, he was able to ward off some of those other individual claims against him. 2 A second hurdle was Wainwright's claim that since he didn't actually run the jails, he shouldn't be sued alone and that unless the counties were joined as -continued on next page. 'We were assisted in Arias by local counsel Randall Berg and Rod Petrey from the Florida justice Institute, William Sheppard, a jacksonville civil rights lawyer, by the Washington law firm of Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering (Lynn Bregman, Stuart Taylor and Ted Killory) and AI Hadeed, a Gainesville civil rights lawyer. 2The ACLU of Texas along with the National Prison Project is involved in a similar statewide jail case against the Texas Commission on jail Standards. The district court granted statewide class certification status over the vigorous opposition of the Attorney General's office. Bush v. Viterna, Civ. Act. No. A-SO-CA-411 (W.D. Tex). The Magistrate recently recommended that the district court deny the defendants' motions to dismiss and/or abstain. SPRING 1985 5 1 -continued from previous page. indispensable party defendants the case should be dismissed. We successfully countered by pointing out that the relief we were seeking would run solely against Wainwright-an injunction requiring him to carry out his standard setting, inspection and enforcement duties. While the counties might be affected by the lawsuit as a result of increased enforcement activities, for example, by being required to install fire safety equipment, this would not require every county to be named as a defendant. They could protect their interests by defending against enforcement actions in state court and by utilizing Florida's Administrative Procedure Act to participate in rule-making proceedings. The court agreed with us and denied the motion to dismiss. Any injunction, the court noted, would have "no greater financial impact on the local governments than they should ordinarily expect ... provided ,~he facilities are lawfully operated . . . . Another serious issue involved the extent of proof. Would we have to demonstrate that the conditions in each of the jails were unconstitutional? If so, there would be little advantage to filing one case rather than hundreds. Or, could we proceed by proving a general pattern and practice of violations? Because we settled the case prior to trial, we didn't get a definitive ruling, but the Magistrate did indicate that it would not be necessary to prove violations in every jail. In any event, from the evidence we accumulated during depositions of the inspectors and review The legal stumbling block was to find a way of linking all of the separately run jails into a statewide action. of their own records, it was easy to show that there were widespread violations-e.g., many jails did not have a contract with a medical doctor, did not prOVide incoming medical or mental health screening, did not provide inmates with exercise. And Wainwright could hardly deny that he had failed to exercise his enforcement duties since he had never sued a single jail; he had in fact made an intentional decision not to resort to court proceedings to enforce the law. Another critical issue arose when Wainwright claimed that the jails were off limits to our expert witnesses. He claimed that he lacked authority to allow our experts into the jails because the sheriffs, not the state of Florida, were 6 SPRING 1985 This is not to say that Florida's jails are now constitutional, or that they have even entered the twentieth century. in charge of the jails. We argued that under Rule 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Wainwright had sufficient "control" over the jails to allow access by our experts. This control, we asserted, derived from Wainwright's power under state law to have his own inspectors inspect the jails. We simply wanted our experts to stand in the shoes of his inspectors who could visit the jails at any time. The Court disagreed with our analysis but said we had a remedy available, namely to bring separate proceedings against the jails for the limited purpose of access, which is allowed pursuant to Rule 34(c). That is what we did, simply by filing petitions for access, and the counties consented to the expert tours. After receiving the favorable opinion from the Court denying all of Wainwright's motions to dismiss, and following extensive document reviews and tours of the jails which demonstrated that our allegations had a strong factual basis, Wainwright initiated settlement discussions. We finally reached agreement on a consent decree which reqUired Wainwright to carry out thorough and complete inspections of each jail at least twice each year and required him to "vigorously, promptly, effectively and thoroughly" exercise his enforcement responsibilities by taking non-complying counties into court. We put some teeth into that obligation by requiring Wainwright to initiate court action within seven days after he was notified of the existence of an "aggravated violation," that is, one that "appears to pose a substantial and immediate danger to life, health or safety." The inadequacy of the jail standards presented one of the most difficult aspects of the case, and we spent dozens of hours negotiating with Wainwright to resolve it. Ultimately we were able to upgrade the standards in key respects: increased space standards were set to reduce overcrowding; some medical screening was instituted, as well as daily sick call, and comprehensive medical care; compliance with fire safety and public health codes was required along with improved classification of inmates. Despite these significant improvements, no agreement was reached on other important issues such as exercise, time out of cell, contact visiting, phone calls and new construction. 3 Therefore, one area 3Wainwright recently promulgated changes in the of the original complaint, the adequacy of the standards, remains open for possible further negotiation, litigation or both. In this part of the case as well as others, the Florida Sheriffs Association played an important behind the scenes role. While not named as defendants, the Sheriffs perceived the case as a vehicle for upgrading the jails by providing more resources and attention from county government, and helped us make some improvements. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, they never went as far as we had hop~d. Since the decree was entered, we have begun to see gradual improvement in the conditions of some of Florida's jails. The inspection staff has been increased, and the inspectors are conducting somewhat more thorough inspections. On the critical issue of fire safety, Wainwright, under pressure from us, has worked out arrangements to have the State Fire Marshall inspect county jails. And for the first time, Wainwright has exercised his enforcement powers by bringing nine counties into state court because of serious jail violations. Some counties are responding to this pressure by hiring staff and developing alternatives to incarceration (release on recognizance, bonding, and prqbation). While we advocate further development of less costly alternatives to incarceration, or renovation of existing jail space, some counties unfortunately are contemplating expensive new construction as the way to meet minimal standards. • Death Penalty Information Packet Update Available The Institute for Southern Studies has released the second edition of its "Death Penalty Information Packet." This new edition has been updated, revised, and redesigned. It contains I I fact sheets, up-todate statistics, and answers to new questions. The cost of each packet is $2, plus 50 cents each for shipping and handling. The cost is $1.50 per packet for orders of 10 or more. Send check payable to the Institute for Southern Studies, P.O. Box 531, Durham, N.C. 27702. regulations requiring, for the first time, two hours of outdoor exercise per week. and "reasonable" access to a telephone. Photo courtesy Rhode fslond Department of Corrections. "Old Max" as it looked in May of 1978. As a result of over seven years of National Prison Project litigation, conditions such as this have been eliminated. Rhode Island's Prisons -continued from front page. Rhode Island is one of the few states that has a unified detention system where the state is responsible for holding pre-trial detainees. There are no local jails. As we walked through the oldest and darkest part of "Old Max" where the men awaiting trial were kept in their filthy cells most of the day, I told one of the judge's law clerks (who was, literally, gagging) that he was witnessing the presumption of innocence on a firsthand basis. On August 10, 1977, Judge Pettine issued his opinion and order in the case.' 'Palmigiano v. Garrahy, 443 F.Supp. 956 (D.R.1. 1977). After pages of factual findings which detailed the filth, "maddening" noise levels, fire hazards, antiquated and unhealthy plumbing, heating and ventilation, and cockroach, rat and mouse infestation, he concluded that "Maximum presents an imminent public health, fire and safety hazard." He found that "staff [were] so accustomed to conditions of deterioration that they had become inured to what they lived with," and, that "on the basis of living conditions alone, Maximum is clearly unfit for human habitation. " The court also found that, as a direct consequence of the "failure of the classification system," the enforced idleness" and the lack of staff control, "rampant violence and endemic fear of violence" existed in the prison system, and that the prison officials had "knowingly and recklessly permitted a reign of terror to develop and exist." Inmates were "forced to live in constant fear of violence and sexual assault." Based upon evidence presented at the trial, Judge Pettine found: "A study of reported incidents of violence during 1975 and 1976 indicates approximately 155 assaults, rapes and major fights per year; 330 other incidents of violence, personal harm to inmates, or mutinous acts; 35 fires; and over 400 reported drug violations per year." The court went on to detail other gross constitutional violations at other facilities and in medical and mental health -continued on next page. SPRING 1985 7 n .. s --Continued from previous page. care throughout the system. Finally, Judge Pettine entered a detailed remedial order which required, inter olio: that the Rhode Island authorities house pre-trial detainees separate from sentenced prisoners, that the maximum security prison be closed within a year, that all prisoners be accommodated in conditions meeting minimum standards, and that a special master be appointed, empowered to monitor compliance. Seven years later the old maximum security prison in Rhode Island remains in use, although not the whole building and with many fewer prisoners. Until January of 1984, the Department of Corrections was still subject to regular inspection by a special master and he can still be called upon by the court on an as-needed basis. As recently as the summer of 1983, the Rhode Island Governor and the Director of Corrections were held in contempt of earlier decrees. Court proceedings still continue . on the basis that some conditions for prisoners remain below the constitutional minima set by the court in 1977. There have been some dramatic changes, however. The Director of Corrections in 1977 (to whom the judge presumably referred in his opinion when he stated that "there is a complete absence of effective leadership or management capability") has been dismissed by the Governor on the recommendation of the special master. Prior to 1977 there was virtually no written administrative policy; now there are agreed procedures and standards for almost every aspect of the prison regime with copies of manuals furnished to prisoners. Two entirely new prisons have been built and brought into use-one for pre-trial detainees and a small (96 bed) high security facility-and a substantial work release center opened. There has not been a serious incident of violence at "Old Max" in more than three years. Had the population of Rhode Island's prison system remained at the 1977 level, the hundred year old maximum security prison mght have been closed, if not within the year ordered by the court then at least by 1982, when the two new facilities opened. But by 1982 Rhode Island's average daily prison population had risen by over fifty percent and has since exceeded the 1977 level by over ninety percent. During the period since 1977 the court has held back from drastic remedies. The deadlines originally ordered for the closure of "Old Max" and for the segregation of detainees were repeatedly extended by Judge Pettine. Despite written reports from the master to the effect that the defendants were dragging their feet because they were confident 8 SPRING 1985 , The old law of an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind. . -Martin Luther King, Jr. The Death Penalty Is Still Wrong L.e. Dorsey On December 5, 1984, Melvin died on an operating table in a Dallas, Texas hospital from a shotgun blast to the stomach. He had argued with Anderson Price, a 67 year old man, who grabbed his shotgun. Reports from the Crimes Against Persons Division of the Dallas Police Department said Melvin struggled with Price for the gun, and was shot during the strusgle. Because of the ongoing investigation, no additional information was available. Oh, yes, the body was at the city morgue and could be claimed by the next of kin. Melvin Louis Braison was born June 20, 1948, to Mr. and Mrs. Leroy "the court will not step in and order them to close the facility down forthwith," the judge was unwilling to decree measures which would, in effect, compel the release of large numbers of prisoners. Deadlines for closure were extended for various reasons: I) pending the outcome of a state referendum in 1980 on a special bond issue to pay for the expansion of the new high security unit (it was overwhelmingly rejected by the voters); 2) awaiting the opening of a prison under construction, or 3) on the basis of reports from the master indicating that although conditions were not fully in compliance with agreed standards, they were greatly improved. For many years the administrators believed that they were in a hopelessly unworkable situation. Despite an influx of funds for the first two years after the court decree in 1977, they began thereafter to receive only minimal financial support from the legislature partly because this was a period of serious financial problems for the state. The dramatic rise in the number of persons committed by the courts, the product of tougher bail conditions and sentencing, made it totally unreasonable from their standpoint to close "Old Max." They saw themselves as sandwiched between a legislature unwilling to increase the budget, sentencers increasingly committing offenders to custody, and counsel for the prisoners pressing for full implementation of an aging decree which the administrators perceived to have been overtaken by events. Beginning in 1981, more funds did become available to the prison officials enabling them to plan, for the first time, to try to comply with the court decree. And, shortly thereafter, they began to work with counsel for the prisoners on a cooperative, rather than adversarial, basis with both sides haVing a common objective of a constitutional prison system. Matters changed even more substantially in 1983 when the voters approved a state bond referendum which gave the Department of Corrections $5.5 million dollars to completely renovate and update "Old Max." After a series of hearings in 1984, the court created a new timetable for bringing that facility into full compliance with its . earlier decrees and also established a reporting mechanism to ensure that the various facilities did not fall below constitutional requirements because of population pressures. I toured "Old Max" recently with the same environmental health expert who had testified that the facility was unfit for human habitation in 1977. He found it difficult to believe that it was the same place. In addition to the work that had been done on fire safety, lighting, plumbing, electrical wiring, ventilation and other physical conditions, the cellblock areas were spotlessly clean and there were no prisoners there. They were all out of the housing area, busily engaged in some activity-recreation, industries, vocational training or educational programs. The Lieutenant who escorted us, and who had been at the prison since before 1977, commented on what a relaxed place it now was to work in and how easy it was to get along with prisoners. The Warden said: "We used to treat them like animals and they behaved like animals. Now they have a decent place to live and work and they behave like decent men." Most important, prisoners regard "Old Max" as the preferred housing in the Rhode Island system. Litigation may not be the perfect vehicle for social change, but seven years of judicial involvement in this state's prison system has made a difference. • Braison. He was the youngest of three brothers born to the union. He was Black, male, poorly educated, and was employed at the time of his death. He had travelled to Dallas almost three years earlier, looking for work and a new beginning. He'd left behind a wife and two daughters. Born in the Mississippi Delta on a government agricultural experiment farm, he came into a world of poverty and difficulty. When his father came to fetch his maternal grandmother to care for the mother, new baby and the two toddlers, he told her that both mother and child had nearly died. He'd taken a long time to be born. The mid-wife finally laid him in his mother's arms in the three room shack, which was provided for good tractor drivers. Melvin, even as a baby, had spirit. He would never become one of the bowed, cowed, broken-spirited Black men who shuffled along the dirt roads of the Delta. He stood up for himself. Melvin had a terrific sense of humor, and any family gathering that Melvin attended was sure to be spiked with laughter. He enjoyed making people laugh. And he enjoyed family gatherings. The big, noisy clan that he was part of got together often, and he managed to get his share of attention, laughs, and sometimes, other family members' goat. He was a favorite of the younger kids who never took him seriously as a grown-up. "Melvin, come and play with us," they'd call out to him. And he'd make a serious face and scowl: "Don't you know I'm grown?" Often the scowl would collapse into smiles or laughter. Melvin was generous. If he had only one dime and someone needed the dime, he'd give it to you and never think about it. If he could help you do something, he would. Melvin had a temper; a quick temper that would appear in an instant, accompanied by loud cusses and threats. But he was unable to maintain that anger No Comment Former Texas death row inmate Charles Brooks complained on june 18, 1982 about the loss of his watch and ring. He submitted a grievance asking that they be returned or that he be reimbursed for their cost. The response, dated December 14, 1982, reads: "Charlie Brooks was executed 7 December 1982. Grievance is moot." From the Ninth Monitor's Report, September 13, 1983, Ruiz v. Estelle. very long or to hold a grudge. He had been known to collapse in a fit of giggles in the middle of threatening to "beat your a--." Or to go and sit down quietly if one of his elder relatives told him to. Melvin drank, and liquor brought out the anger. At home in Indianola, Mississippi and later in Memphis, Tennessee, when he had too much to drink and began to hassle people, someone would simply take him home or find a relative to come and get him. His family thinks that if he'd been at home, he'd still be alive. Melvin's body was flown back to Mississippi and buried at a little church in the country not too far from where he was born, went to school, played, dreamed, and suffered the agonies of racism and poverty. The family of poor people put him away nicely. They say he wore a smile on his still youthful face. Melvin was my older sister's youngest son. We grew up together, although I'm older. I nursed, bathed and took care of him when he was a baby and later, when my oldest child was born, he returned the favor. Melvin understood why I worked with prisoners and was opposed to the death penalty, and supported my work. He had felt the harsh hand of the law as a teenager, for truancy and fighting. He later served some months in prison for assault. He knew about the fear and horror of the inside world. I'm often asked by reporters and proponents of the death penalty how I would feel about the death penalty if someone I loved was killed. And I've always answered honestly, that I didn't know how I'd feel. Well now I know. The telephone rang in the middle of the night in the dingy, old, walk-up rent controlled apartl"Qent building where I live. Melvin's brother, Leroy, was on the other end of the line. He told me Melvin was dead. He gave me the details, the detective's number and the number at the morgue. We called the rest of the family with our awful message. I felt dead inside. I waited for the anger to come, but it didn't come. I waited for the tears to flow, but it was as if I was suddenly dead-dried up-inside. Hours later, I went to bed and waited for sleep, which didn't come either. In the next hectic 72 hours, I felt angry, but not at the faceless old man -continued on page 10. Information on Jails Available to Media Do you know? • 7 million people pass through our local jails each year? • 10.7 percent of all jails are under court order to improve conditions? • the suicide rate for adults in jail is 16 times greater than for the general population; most of those who kill themselves are drunk at the time? • the average cost of housing one person in jail for a year is $14,000? • the cost of building one new jail cell is between $50,000 and $70,OOO? A new information packet, Covering Your Jail: Resources for the Media, presents the facts about 14 major jail issues. Prepared by the National Coalition for jail Reform and distributed to 4,000 newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations across the country, the packet is also being used by county commissioners, sheriffs, and local planners. This two-color, glossy paper packet with up-to-date statistics and photographs covers the following topics: What Is a jail? Who Is in jail? What Does a jail Cost? jail Crowding jails Operated by Private Companies jail Conditions and Standards Alternatives to jail Legal Issues Contributing to Solutions: the Community and the Criminal justice System In addition, there are sections on women in jail, juveniles, the mentally ill, drunk drivers, and suicides in jail. The packet is being used by nonmedia people to: • obtain more positive press coverage of the jail; • help jail administrators deal with the press; • train new jail staff on issues; • educate elected officials about their jail; • help judges, police, prosecutors and others to understand jail problems; • educate community leaders about jail issues. Copies of the packet are available for $ I0 each including postage and handling from the National Coalition for jail Reform, 1828 L Street, N.W., Suite 1200, Washington, D.C. 20036, telephone 202/296-8630. • SPRING 1985 9 Photo by Philip B. Toft. Jr. -<ontinued from page 9. who had ended Melvin's laughter, but at the poverty that made some of us choose between going to the funeral or sending money to help with the funeral arrangements. Why do people have to choose in these crucial family times? I felt pain when a friend, whom I'd called to ask about agency help to get the body home, asked me, in all sincerity, why were we trying to bring him home? She really didn't know that we couldn't leave Melvin in a strange place where his spirit would be restless and lonely. Loneliness is terrible. I felt powerless as my younger sister turned to me to understand how he died. Who would kill Melvin? Why? It was terribly important for her to know. I kept trying to explain that to the Division of Crimes Against Persons, but they didn't understand Emma and the shock of this violence to her gentle spirit. They couldn't give any more information. I think about Mr. Anderson Price and wonder what he is like. Was this his first killing? Was he traumatized? Is he alone in a jail cell, or is he back at home, smoking a pipe, or rocking in his favorite chair or doing whatever he was doing before he pulled the trigger on December 5? My mind won't let me feel anger towards him. Perhaps it's the social work training, or that I know how frightened senior citizens are of young males. We don't know whether Mr. Price is Black or White, and although one witness has contacted the family to tell us that Melvin was murdered in cold blood, we know that we will never know what happened. And what would Melvin say should happen to Mr. Price if I could ask him? I don't know. I never thought to ask him. I would imagine, knowing Melvin's philosophical nature, that he would say, "Now L.e., what good would killing him do? That'd just be two people dead then." And thinking about his wisdom, he'd laugh o~ loud. I now know what the answer is the next time someone who believes in executions asks: "How would you feel if it was someone you loved?" I will answer:' dead and dry inside. And I know with a certainty from which fate has removed the last crucible of doubt, that the death penalty is wrong, and that executing Mr. Price won't bring back Melvin's laughter. L.c. Dorsey is a member of the D.C. Coalition Against the Death Penalty and is on the National Prison Project Steering Committee. She is the former director of the Mississippi branch of the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons. I 10 SPRING "85 Inmates jam bullpens in this overcrowded Essex County Jail in Newark, New Jersey. National Prison Project Status Report Released The National Prison Project has released its most recent "Status Report" on prison conditions. The report reveals the crisis the United States is facing in its prisons due to overcrowding. Studies done on prison problems conducted since the 1972 Attica uprising show that the root causes of most prison disturbances, as well as the current crisis in corrections, are overcrowding and unconstitutional conditions. Thirty-four states are operating their prisons under court orders because of violations of the constitutional rights of prisoners. Those states are: Ari- zona,' California, Colorado,' Connecticut,' Delaware,' Florida,' Georgia,' Idaho,' Illinois,' Indiana,' Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky,' Louisiana, Maryland, Michigan,' Mississippi, Missouri,' Nevada,' New Hampshire,' New Mexico,' Ohio,' Oklahoma,' Pennsylvania, Rhode Island,' South Carolina,' South Dakota,' Tennessee,' Texas, Utah, Virginia,' Washington,' West Virginia,' Wisconsin'. In addition, Washington, D.e. (jail), Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands are under court order. (Court •Asterisks indicate states where the ACLU is involved in the litigation . J' orders involving jails are not listed with the exception of Washington, D.C.) Each of these orders has been issued in connection with total conditions of confinement and/or overcrowding which resulted in prisoners being subjected to cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. There are four more states under court order than there were one year ago. Conditions of confinement are presently being challenged in ten states: Hawaii,' Massachusetts, North Carolina, South Carolina,' Washington, Arizona,' Illinois,' Michigan,' Pennsylvania, Virginia·. Four of these states, Arizona,' South Carolina,' Washington' and Virginia,' already have one or more prisons under court order. Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director of the Prison Project, said, "Once again, our annual survey shows the continuing and critical problem of overcrowding and uncivilized conditions in our prisons, when two-thirds of our states have been found to be in violation of one of the most fundamental of our QTY. COST The National Prison Project JOURNAL, $IS/yr. $2/yr. to prisoners. Back issues, $1 ea. The Prisoners' Assistance Directory, the result of a national survey, identifies and describes various organizations and agencies that provide assistance to prisoners. Lists national, state, and local organizations and sources of assistance including legal, library, medical, educational, employment and financial aid. 6th edition, published January 1985. Paperback, $1 5 prepaid from NPP. Offender Rights Litigation: Historical and- Future Developments. A book chapter by Alvin J. Bronstein published in the Prisoners' Rights Sourcebook (1980). Traces the history of the prisoners' rights movement and surveys the state of the law on various prison issues (many case citations). 24 pages, $2.50 prepaid from NPP. Fill out and send with check payable to The National Prison Project 1346 Connecticut Ave. NW Washington, D.C. 20036 constitutional rights, the right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment." The National Prison Project does not, however, support construction of additional prison space as a simple answer to the overcrowding problem. We urge the formulation of a national, long-range criminal justice policy which would include,. among other things, the use of probation, community service sentencing and victim restitution as alternative forms of punishment. Copies of this report are available from the Prison 'Project for $3.00. 11III QTY. COST The National Prison Project Status Report lists each state presently under court order, or dealing with pending litigation in the entire state prison system or major institutions in the state which deal with overcrowding and/or the total conditions of confinement. (No jails except District of Columbia). Periodically updated. $3 prepaid from NPP. Bibliography of Women in Prison Issues.' A bibliography of all the information on this subject contained in our files. Includes information on abortion, behavior modification programs, lists of other bibliographies, Bureau of Prison policies affecting women in prison, juvenile girls, women in jail, the problem of incarcerated mothers, health care, and general articles and books. $5 prepaid from NPP. A Primer For Jail Litigators is a detailed manual with practical suggestions for jail litigation. It includes chapters on legal analysis, the use of expert witnesses, class actions, attorneys' fees, enforcement, discovery, defenses' proof, remedies, and many practical suggestions. Relevant case citations and correctional standards. Ist edition, February I984. 180 pages, paperback, $1 5 prepaid from NPP. NAME Prisoners' Rights 1979. Course handbooks prepared for the Prisoners' Rights National Training Programs held January-March 1979. Includes ",',/' >./ articles, legal analyses, and litigation forms. Prepared by the staff of the National Prison Project. Available in paperback. $35 per set, from the Practising "-/, / ,,,,' Law Institute, 810 Seventh Ave., New York, N.Y. 10019. 2 Vols., 1163 pages. This set, plus Representing Prisoners (below), can be purchased for $40. I/'_/'_V'_/'_/' Representing Prisoners. The course handbook prepared for the Prisoners' Rights National Training Programs held in June and July I98 I. Includes articles, legal analyses, and litigation forms. Prepared by the staff of the National Prison Project. Available in paperback from the Practising Law Institute, 810 Seventh Ave., New York, N.Y. 10019. I Vol., 980 pages. $35. ACLU Handbook, The Rights of Prisoners. A guide to the legal rights of prisoners, pre-trial detainees, in questionand-answer format with case citations. Bantam Books, April 1983. Paperback, $3.95 from ACLU, 132 West 43rd St., New York, N.Y. 10036. Free to prisoners. _ ADDRESS . CITY, STATE, ZIP _ SPRING 1985 II l IIIIEI The following are major developments in the Prison Project's litigation program since October 15, 1984. Further details of any of the listed cases may be obtained by writing the Project. recommends that the court deny the various motions to dismiss the case filed by the defendants, and validated our theory of supervisory ability. Canterino v. Wilson - This case chalBlack v. Ricketts - This case challenges conditions and practices at a special large segregation unit at the Arizona State Prison. All attempts at negotiating a settlement broke down after a major shake-up in the Department of Corrections. We conducted extensive discovery for a trial which commenced on February 5, 1985. Brown v. Lar1don - This case challenged conditions and practices at the super-maximum security prison (Mecklenburg Correctional Center) in Virginia. In early December, we filed a motion seeking to hold state officials in contempt for failing to comply with a consent decree that was entered in 1983. Shortly thereafter, the Director of Corrections resigned and a new Director was appointed who immediately announced sweeping changes at this facility. We are presently reviewing these proposed changes which would appear to accomplish all of the original objectives of the litigation. Bush v. Viterna - This is a statewide class action challenging certain actions of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards in regulating the conditions and practices in all of the county jails in Texas. In December, we received a favorable opinion from the Magistrate in which he National Prison Project American Civil Liberties Union Foundation 1346 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Suite 402 Washington, DC 20036 12 SPRING 1985 lenged the totality of conditions and a degrading behavior modification program called the "levels" system at the Kentucky Correctional Institution for Women. Following up several earlier favorable decisions we determined in November that the level system is no longer operating at the facility. On January 9, we received a favorable opinion on our motion for an interim award for attorneys' fees and costs. Duran v. Anaya - This is a statewide prison conditions case in New Mexico. The Special Master issued a series of reports in November and December finding the defendants in non-compliance with portions of the earlier court orders and we began preparing for pOSSible formal compliance hearings. Flittie v. Solem - This case challenges conditions at the South Dakota Penitentiary and, in response to an earlier favorable ruling, the defendants filed their plans for correcting various deficiencies in November. Nelson v. Leeke - In this statewide prison conditions case in South Carolina, all the relevant state agencies approved the proposed settlement agreement, including funding, and the agreement was formally signed on January 8, 1985. Palmigiano .v. Garrahy - This is the statewide Rhode Island prison case in which we earlier obtained a ruling declaring the entire system unconstitutional. After a series of negotiating conferences, the c2>urt on November 19 entered a new remedial order setting forth new compliance and reporting schedules in the light of the substantial compliance efforts made by the defendants to date. Pugh and James v. Britton - As a result of recent inspection tours, we concluded that the state was in substantial compliance with earlier court orders in the state-wide Alabama prison case. Accordingly, an agreement was reached and incorporated in an order on November 27 ending active court supervision of the case. However, the Implementation Committee will continue monitoring for compliance for another 18 months and the court's jurisdiction can be reactivated upon application during that period. Spear v. Ariyoshi - This is a recently filed case which challenges conditions and practices at the men's and women's prisons in Hawaii. During November, December and January we conducted six expert tours of the facilities as we began full-scale discovery in the case. Witke v. Crowl - In this case, which challenged conditions and practices at the Women's Prison in Idaho, a notice to the plaintiff class of the final settlement agreement was delivered on November 20 and we anticipate court approval by this printing. • Nonprofit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Washington. D.C. Permit No. 5248 ~C"39