Journal 5-3

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN CIVil LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL 5, NO.3, SUMMER 1990· ISSN 0~48-2655

'Iii

,

In Pennsylvania, 200 Years ofPractice

Doesn't Make Perfect

BY; STEFAN PRESSER

Pproximately 200 years after

Pennsylvania opened the world's

first penitentiary, the state

Department of Corrections has found

itself on the verge of collapse. As a result

of either riots or threats of riots, it has

been forced to put one after another of

its institutions on lockdown. With its

third largest facility burned to the

ground, Pennsylvania's acting corrections

commissioner on March 7 of this year

A

faxed the following message to his

colleagues: "Please be advised that we

have reached the critical point of zero

available beds in the Department of

Corrections," while noting that "new

commitments continue to arrive at an

accelerated rate."

While the Department has just

recently lost control of its operation, the

problems inherent in the penitentiary

system are as old as the concept itself.

The idea of the penitentiary was based

on the Quaker belief that "the best way

to reform criminals was to lock them in

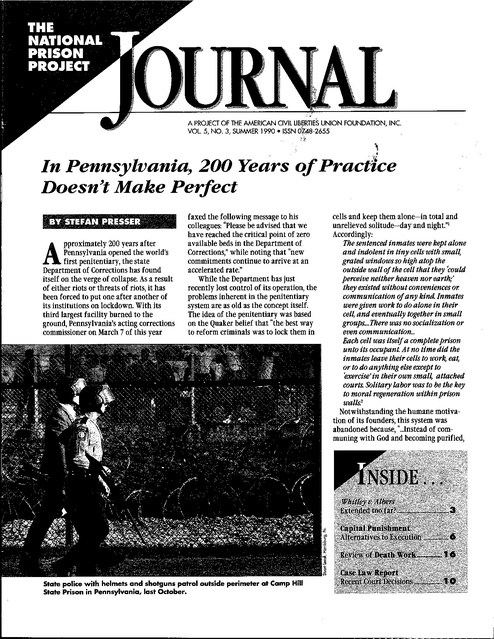

State police with helmets and shotguns patrol outside perimeter at Camp Hill

State Prison in Pennsylvania, last October.

cells and keep them alone-in total and

unrelieved solitude-day and night."1

Accordingly:

The sentenced inmates were kept alone

and indolent in tiny cells with sman

grated windows so high atop the

outside wall of the cell that they could

perceive neither heaven nor earth;'

they existed without conveniences or.

communication ofany kind. Inmates

were given work to do alone in their

cen and eventually together in small

groups....There was no socialization or

even communication...

Each cell was itselfa completeprison

unto its occupant. At no time did the

inmates leave their cells to work, eat

or to do anything else except to

exercise'in their own sman attached

courts. Solitary labor was to be the key

to moral regeneration within prison

walls.2

Notwithstanding the humane motivation of its founders, this system was

abandoned because, ",..Instead of communing with God and becoming purified,

State police lining up outside the state correctional institution at Camp Hill,

Pennsylvania, during the October 1989 disturbance.

the men imprisoned went insane,

committed suicide, or died due to the

extreme conditions. As Thomas Mott

Osborne, one of our foremost prison

administrators, has said, 'In attempting to

reform men by forcing them to think

right, by locking them in a

solitary cell with a Bible, the

Quakers showed a touching

faith in human nature,

although precious little

knowledge of it.'''3 Their

successors in the Department

of Corrections seem to have

gleaned little more of

human nature in the ensuing 200 years.

Over 19,000 individuals were being

held in 13 state prisons meant altogether

to hold no more than 12,000. On the night

of October 23, 1989, a number of prisoners

at Huntingdon refused to lock down after

dinner. Whether due to double-ceIling,

cutbacks in prllgrams and other services,

or to some other factor which will never

be fully understood, on that night about

25 prisoners began a rampage.

Huntingdon then went on 24-hour

lockdown which lasted for much of the

rest of that fall.

Two days later the Department lost

control of its second largest prison. Built

in 1941 with a capacity of approximately

1,800 beds, Camp Hill was by then

housing over 2,600 inmates. As a result,

inmates' access to medical, legal, and

programmatic opportunities had diminished to a point where many prisoners

remained idle for the duration of their

incarceration. Inmate frustration finally

exploded as word of further cutbacks in

medical and visitation programs circulated. On October 25, at approximately

2:45 p.m., an inmate attack on a guard

turned into a general melee. Over the

course of the next several hours prisoners

seized hostages and control of several

buildings. From

these hostages,

the prisoners

were able to

obtain cellblock

keys as well as

radios which

they used to

begin negotiations with the Department.

By mid-evening, negotiations had

resulted in a commitment from the

prisoners to release the hostages, and to

return voluntarily to their cells in

exchange for the Department's promise to

continue the dialogue over inmate

grievances. Even though officials knew

that Camp Hill's security system had been

badly damaged, they allowed inmates to

return to their cells without further

search. When the following day's

negotiation proved fruitless from the

inmates' perspective, they simply released

themselves and proceeded for a second

straight day to seize control of the

institution. During the second melee, a

large part of Camp Hill went up in

flames. For the better part of a day and a

half, prisoners held nearly 1,000 correctional officers and state police at bay.

To the extent that the Department had

been nonchalant in its response to the

first incident, officials now acted with

draconian overkill to retake Camp Hill.

Two days later the

Department lost

control of its second

largestprison.

2 SUMMER 1990

Having quelled the riot, officers stripped

prisoners to their underwear. Each was

flexicuffed as well as shackled to another

inmate. They remained out-of-doors in

that state of undress and restraint for the

next three days during brutally cold

weather. When the prisoners were at last

brought back indoors, they remained

cuffed and shackled. They remained in

these restraints for the next 14 days,

despite the fact that each cell was now

triple-padlocked, until the Pennsylvania

ACLU could secu~ a federal court order.

The world didJfot learn of these

conditions (or tfutt the Department was

notproviding toilet paper, mattresses,

pillows, or showers) until the first

postcards began trickling out of Camp

Hill. So bizarre and barbaric were these

descriptions that when they were first

brought to ACLU's attention, I simply

refused to accept them at face value. It

was only after corrections officials

confirmed the shackling-intended to be

of indefinite duration-that we decided

to file for injunctive relief, even though

the Department assured us that prisoners

were not without toilet paper, clothing,

mattresses, and the like.

Despite corrections officials' protestation that prisoners were not being

abused, the testimony in Arbogastv.

Oweni' proved that the shackled inmates

were being forced to sleep in a state of

Editor: Jan Elvin

Editorial Asst.: Betsy Bernat

Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director

The National Prison Project of the

American Civil Uberties Union Foundation

1616 P Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 331-0500

The National Prison Project is a tox-exempt foundationfunded project af the ACLU Foundotion which seeks to

strengthen and protect the rights of adult and juvenile

offenders; to improve overall conditions in correctional

facilities by using existing administrative, legislative and

judicial channels; ond to develop alternatives to

incarceration.

The reprinting of JOURNAL materiol is encouraged with

the stipulation that the Notional Prison Project JOURNAL

be credited with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint

be sent to the editor.

The JOURNAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by

the National Prison Project. Materiols and suggestions

are welcome.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

undress on the concrete cell floor.

Moreover, unrebutted testimony established that the Department was not

providing such essentials as toilet paper.

While I never doubted that Judge Rambo,

to whom this case was assigned, would

order that basic items of civilization be

afforded, it was not at all clear whether

she would force the state to unshackle

our clients. We were especially pleased

when the court concluded:

The measures taken to restrain the

inmates is much more a matter of

institutional security. However, given

the general disdain for the use of

shackles to restrain inmates (see cases

cited in Plaintiffs' memorandum at

4-5) and thefact that the cells at

camp Hill are locked with three

different mechanisms, the court

believes that the continued use of

shackles is not necessary. In any event

the court cannot say thatplaintiffs

lack a reasonable probability of

success on the merits of their claims so

as to preclude them from obtaining

injunctive reliej5

Within days of the entry of this order,

the Department put its largest facility on

lockdown to avoid another Camp Hill.

With 3,400 prisoners, Graterford was not

only one of the nation's largest prisons

but was at that time 1,000 prisoners over

capacity.

As of the writing of this article, the

situation is so bad that in order to

alleviate overcrowding at Graterford

(the population of which is now ovet:;i,

4,000), the Department is contempll,l,ting

moving several hundred Graterford':~

inmates to Camp Hill, which is stiltih the

process of being put back on line. it

Sadly, one can only conclude that if

Pennsylvania, with its 200 years of

experience, cannot make the penitentiary

system work, it is time for some creative

alternative forms of punishment. _

lR. Goldfarb & L. Singer, After Conviction (1973).

'[d. at 24-25.

3[d. at

37.

41:CV-89-1592 (M.D.Pa.1989)'

5Memorandum And Order (November 8, 1989 at p. 4).

Stefan Presser is the legal director Of the

ACLUofPennsylvania.

The.Lost Meaning of

Whitley v. Albers

B¥ MA.RK LOPEZ

A.ND DllVID FATMI

raditionally, the Eighth Amendment prohibition against "cruel and

unusual punishment" has meant

different things in different contexts.

When a prisoner complained of overcrowding and deleterious conditions, an

Eighth Aml;Jldment violation was

established if he could show "wanton and

unnecessary infliction of pain," Rhodes v.

Chapman,! to be measured by the oftquoted "totality of conditions" test. Hutto

v. Finney.2 If he alleged that he was being

denied medical care, or protection from

assault by other prisoners, the standard

used was "deliberate indifference." Estelle

v. Gamble,3 Davidson v. Cannori'.

In 1986 the Supreme Court for the first

time introduced an explicit intent

requirement into Eighth Amendment

jurisprudence, holding that a prisoner

injured while authorities are suppressing

a prison riot can recover only if officials

used force "maliciously and sadistically

for the very purpose of causing harm."

T

II

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

Whitley v. Albers.5

Many courts, in their enthusiasm to

extinguish prisoners' rights, have sought

to extend Whitley's "malicious and

sadistic" threshold far beyond the prison

riot context to coverall uses of force by

prison authorities and, more importantly,

all Eighth Amendment claims involving

prison conditions.

Whitley v. Alberi' was brought under

42 U.S.C. § 1983 by a prisoner who had

been shot by a guard in the course of

quelling a prison disturbance. The prisoner alleged that the shooting violated

his Eighth Amendment right to be free

from cruel and unusual punishment.

The Court, by a five-to-four margin,

decided in favor of the prison officials.

The Court first outlined the general

standard for establishing violations of

the Eighth Amendment: "It is obduracy

and wantonness, not inadvertence or

error in good faith, that characterize the

conduct prohibited by the Cruel and

Unusual Punishments Clause, whether

that conduct occurs in connection with

establishing conditions of confinement,

supplying medical needs, or restoring

official control over a tumultuous

cellblock."7 In the context of a prison riot,

officers demonstrated obduracy and

wantonness only if they used force

"maliciously and sadistically for the very

purpose of causing harm."8 Since, according to the Court, there was no evidence in

this case that prison officials had acted

"maliciously and sadistically," the district

court had properly directed a verdict in

their favor.

Justice Marshall, in dissent, protested

the majoritY1 invention of a separate,

"especiallyo.lJerous" standard for Eighth

Amendment'!violations during prison

unrest. 9 But, although Whitleywas

unquestionably a step backwards,

prisoner rights advocates hoped it would

be confined to its facts, thus inflicting

minimal damage on Eighth Amendment

law.1O

The Whitle.y court did not purport to

extend the new "malicious and sadistic"

standard to all Eighth Amendment

claims. In fact, it specifically reaffirmed

the holding of Estelle, that "deliberate

indifference" to prisoners' serious

medical needs violates the Eighth

Amendment, noting that "the State's

responsibility to attend to the medical'

needs of prisoners does not ordinarily

clash with other equally important

governmental responsibilities."ll By its

terms then, Whitley seemed to be limited

to cases involving prison uprisings.

Instead, however, lower courts hostile to

prisoners have expanded Whitley far

beyond those situations. Unless the

Supreme Court reverses this trend soon,

what began as a narrow exception now

threatens to swallow the entire Eighth

Amendment.

Indeed, the dissenters in Whitley

foresaw this potential. "The Court

imposes its heightened version of the

'unnecessary and wanton' standard only

when the injury occurred in the course of

a 'disturbance' that 'poses significant

risks,' [citation]. But those very questions-whether a disturbance existed and

whether it posed a risk-are likely to be

hotly contested."12 In Whitley itself, for

example, the majority brushed aside

evidence that the disturbance was

substantially over by the time the shots

were fired. Similarly, in many subsequent

cases in the lower courts, "disturbance"

has been very broadly construed.

For example, in Cowans v. Wyrick,13 a

prisoner, locked in his cell, refused to

shut a food service door. Aguard responded by slamming the door on the

prisoner's hand. The Eighth Circuit held

that the prisoner's refusal was a "disturSUMMER 1990 3

bance indisputably pos[ing] significant

risks to the safety of inmates and prison

staff," and employed the Whitley

"malicious and sadistic" standard to

reverse a judgment for the prisoner.14

Other courts are more candid about their

expansion of Whitley. In Ort v. White,15

the Eleventh Circuit stated its view that

"[a]lthough Whitley was decided in the

extremely volatile context of a prison

riot, its reasoning may be applied to other

prison situations requiring immediate

coercive action" It then found that a

prisoner's refusal to carry a water keg

required such "immediate coercive

action."

The Fourth Circuit may have gone the

furthest in expanding Whitley to cover

all use of force in prison. That court

recently stated: "While the particular

setting of Whitley involved a prison riot,

the standard announced in that case is

not limited to the quelling of institutional disturbances. The Whitley standard

applies to any claim of excessive force to

subdue [a] convicted prisoner, [citation]

or to prophylactic or preventive measures intended to reduce the incidence

oLany other breaches of prison discipline." Miller v. Leathers. 16 The Miller

court affirmed summary judgment for a

guard who had struck a handcuffed

prisoner three times with his baton,

breaking his arm, when the prisoner

refused an order and insulted the guard's

mother. Other courts have applied the

Whitley "malicious and sadistic" standard

to the use of force on a prisoner in the

mess hall,17 and to a guard's use of a baton

on a prisoner's neck when he refused to

enter his celLIs

Fortunately, not all courts have

collapsed the distinction between

quelling a prison riot and all other uses of

force. In Meriwether v. Coughlin,19

prisoners engaged in a nonviolent protest

were beaten by guards. The Second

Circuit declined to apply the Whitley

"malicious and sadistic" standard,

"because no riot was occurring..., nor was

there even, according to the jury, the

degree of unrest that defendants

claimed."20 The Ninth Circuit has similarly declined to apply Whitley to body

cavity searches, where the circumstances

giving rise to the searches "did not

constitute an ongoing prison disturbance

[and] the officers were not confronted

with an instantaneous decision whether

to conduct the searches in the manner

described."2l Bolin v. Blacfi2 did involve a

prison riot, but prisoners were beaten

after the riot was over and prisoners had

been locked down. The Eighth Circuit

4 SUMMER 1990

distinguished Whitley and Cowans,

tack. In Cody v. Hillard,28 that court,

because "[i]nthe instant case, the beatings sitting en bane, reversed the district

complained of by the prisoners occurred

court's order ending double-celling at the

a/terany threat to institutional security

South Dakota State Penitentiary. The

had been quelled.''23

court noted the officials' "sincere efforts

It seems likely that the Supreme Court . to maintain a healthful environment,"

will eventually resolve this conflict in

.~ and concluded that "[t]his hardly reflects

the application of Whitley to use of force '~'~'obduracy and wantonness.'''29 The focus

in prisons. However, it is already clear

. on prison officials' state of mind, rather

that at least three justices are disposed t<>;;;.' ,than on the objective conditions faced by

read that case expansively. Justice

.~.; prisoners, is consistent with the intent

O'Connor has stated her belief, joined b~,~~

requirement of Whitley.

Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice

The implicatioI1§ of the Wilson and

Kennedy, that Whitley should not be

Cody decisions ar~not difficult to predict.

limited only to "full-blown prison riotS."24 Under the standard announced in those

These attempts to extend the Whitley

cases, almost no Eighth Amendment

"malicious and sadistic" standard to all

claim involving conditions of confineuse of force cases are disturbing. But far

ment can be successful, because the test

more ominous are moves to apply that

focuses on the defendants' state of mind

standard to all Eighth Amendment cases,

rather than the objective harm to

specifically those involving ongoing

prisoners. Obviously no administrator

conditions of confinement. Under this

houses prisoners in filthy, overcrowded

approach, prisoners complaining of

conditions without access to medical care

contaminated food or unsanitary

out of malicious cruelty; it occurs as a

conditions in their cells must show that

result of underfunding, inadequate

prison officials deliberately caused these

staffing, or administrative incompetence.

conditions, "maliciously and sadistically

To require prisoners to prove otherwise is

for the very purpose of causing harm."

to impose an almost impossible burden

Obviously such a shOWing, requiring a

and essentially to read the Eighth

probe into the psyche of prison adminisAmendment out of the Constitution.

trators, is extraordinarily difficult to

Moreover, whatever reasons might

make. Nor can such a requirement be

arguably support the "malicious and

reconciled with the high Court's previous

sadistic" standard in the prison riot

decisions in Hutto and Rhodes, which do

context are attenuated or nonexistent

not require such an exacting inquiry.

when continuing conditions are at issue.

Perhaps the most unequivocal stateFirst, the interest in avoiding the secondment to date is the decision of the Sixth

guessing of prison officials is at its zenith

Circuit in Wilson v. Seiter.25 Ohio prisonwhen they are making split-second, lifeers mounted an Eighth Amendment

and-death decisions during an emergency.

challenge to numerous conditions of

This is not the case with conditions that

their confinement, including overcrowdhave persisted essentially unchanged for

ing, excessive noise, inadequate heating

months or years. Second, prison officials

and cooling, and unsanitary eating

are experts in prison security; deference

conditions. Purporting to follow Whitley,

to them is and should be at its height

the court of appeals affirmed the trial

when they make security judgments

court's grant of summary judgment for

regarding the use of force. Where they

the defendants.

make judgments about medical care,

The court first noted that "at least in

nutrition, and environmental health and

this circuit, the Whitley standard is not

safety, they have no special competence

confined to the facts of that case; that is,

and deference is less appropriate.

to lawsuits alleging use of excessive force

It should be emphasized that the

in an effort to restore prison order."26 It

decisions in Wilson and Cody do not

then proceeded to make the standard

represent the unanimous view in the

even more onerous than Whitley had

circuits. Indeed, several sister circuits

done: "the Whitley standard of obduracy

have expressly refused to apply the

and wantonness requires behavior

"malicious and sadistic" standard to

marked by persistent malicious cruelty.''27

conditions cases. Thus, in Foulds v.

Since the defendants' affidavits stated

Corley,30 the Fifth Circuit explicitly

that they had made some attempts to

rejected the trial court's application of

remedy the conditions complained of,

Whitley to a conditions case involving

they could not have acted with the

solitary confinement. "The facts of the

requisite "persistent malicious cruelty;"

instant case markedly differ. There was

thus, summary judgment was appropriate. no imminent danger. We decline the

The Eighth Circuit has taken a similar

invitation to extend the rule of Whitley

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

I

II

to cover all prison disciplinary actions,

ostensibly under the guise of achieving

prison security."31 A different panel of the

Fifth Circuit has similarly stated that the

heightened Whitley standard does not

apply to continuing conditions of

confinement. "Prison conditions may

violate the eighth amendment even if

they are not imposed maliciously or with

the conscious desire to inflict gratuitous

pain."32

Similarly, in LaFaut v. Smith,33 a

handicapped prisoner claimed he had

been denied the basics of personal

hygiene. The Fourth Circuit, in an

opinion by Justice Powell, sitting by

designation, rejected attempts to apply

the heightened Whitley standard to this

claim. "Whether one characterizes the

treatment received by LaFaut as inhumane conditions of confinement, failure

to attend to his medical needs or a

combination of both, it is appropriate to

apply the 'deliberate indifference'

standard articulated in Estelle to this

case."34

Finally, in Morgan v. District of

Columbia,35 the District of Columbia

Circuit likewise rejected application of

the Whitley standard, and applied the

"deliberate indifference" standard to a

prisoner's claim that officials had failed

to protect him from assault by a fellow

prisoner:

The exigencies and competing obligationsfacing prison officials while

attempting to regain control ofa riotous

cellblock, which led the Court to conclude

that the "deliberate indifference»

standard was inadequate in Whitley, are

notpresent in this case. The gravamen of

Morgan's claim is the District's overcrowding of theJai4' the conduct Morgan

challenges is the municipality's operation of theJail generally. In this context

unlike in the prison riot setting, there can

be no legititnate concern that liability

will improperly be based on "decisions

necessarily made in haste, under

pressure, andfrequently without the

luxury ofa secOnd chance. »Whitley, 106

S.Ct. at1085. The District'spractice of

overcrowding has endured since at least

1971 We therefore conclude that "deliberate indifference» was the appropriate

standard by which to judge the District's

conduct in this case.

.

The National Prison Project has filed a

petition for a writ of certiorari in Wilson

v. Seiter, urging the Supreme Court to

review and reverse the Sixth Circuit's

decision in that case. If certiorari is

granted, the Supreme Court's decision

will almost certainly determine the

I

~J

'11

~

1!

i

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

course of prison litigation for years to

come. The Wilson court and others have

served notice of their intention to make

it virtually impossible for prisoners to

successfully challenge the conditions of

their confinement. Unless the Suprem<:

Court takes this opportunity to reversd'

this alarming trend, there will once a~in

be an "iron curtain drawn between t~

Constitution and the prisons of this,;~'.'

country."36 _

1452 U.s. 337, 347.

2437 u.s. 678, 687-688 (1978).

3429 U.s. 97, 104 (1976).

4474 u.s. 344, 347 (1986).

5475 u.s. 312, 320-321 (1986).

6475 U.s. 312 (1986).

7475 u.s. at 319.

8475 U.s. at 320-321.

9475 U.S. at 328 (Marshall,]., dissenting).

IOAccording to the Whitley majority, the case involved

a"prison riot" at the Oregon State Penitentiary. One

officer was assaulted, and another taken hostage.

Prisoners were armed and had set up barricades, and

"the cellblock remained in the control of the

inmates." One prisoner warned officials that a

prisoner had already been killed and other deaths

would follow (in fact, there were no deaths). Faced

with this situation, prison authorities mounted an

armed assault to quell the disturbance. Several

prisoners were wounded by gunfire, including the

plaintiff, who had not participated in the uprising.

475 u.s. at 314-316, 322-323.

"475 u.s. at 320.

12475 U.s. at 329 (Marshall,]., dissenting).

13862 F.2d 697 (8th Cir.1988).

14862 F.2d at 699-700. Judge McMillian, concurring

specially, questioned whether the incident

constituted a"prison disturbance." [d. at 701.

15813 F.2d 318, 323-325 (11th Cir. 1987).

16885 F.2d 151, 153 (4th Cir.1989), internal quotation

marks omitted.

17Corselli V. Coughlin, 842 F.2d 23, 25-26 (2d Cir.1988).

"Brown v. Smith, 813 F.2d 1187, 1188-1189 (llth Cir.

1987).

19879 F.2d 1037 (2d Cir.1989).

20

879 F.2d at 1048.

21 Vaughan v. Ricketts, 859 F.2d 736, 742 (9th Cir.1988).

22875 F.2d 1343. <lith Cir.1989), cert. denied,_U.S'---l

110 S.Ct. 542, 10~ ~.Ed.2d 539 (1989).

23875 F.2d at 1~5R emphasis in original.

24 Dudley v. Stubbs, - U.S.-, 109 S.Ct. 1095, 1097, 103

L.Ed.2d 230 (1989) (O'Connor,]., dissenting) (mem.).

25893 F.2d 861 (6th Cir.1990), cert. pending.

26893 F.2d at 866.

27893 F.2d at 867.

28830 F.2d 912 (8th Cir.1987) (en bane), cert. denied,

485 u.s. 906,108 S.Ct.l078, 99 L.Ed.2d 237 (1988).

29830 F.2d at 915.

30833 F.2d 52 (5th Cir. 1987).

31833 F.2d at 54.

32Gillespie v. Crawford, 833 F.2d 47, 50 (5th Cir. 1987),

partially vacated on othergrounds, 858 F.2d 1101,1103

(5th Cir.1988) (en bane).

33834 F.2d 389 (4th Cir. 1987).

34834 F.2d at 391-392.

35824 F.2d 1049, 1057-58 (D.C. Cir.1987).

36 Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 555-556 (1974).

Mark Lopez and David Fathi are staff

attorneys with the National Prison

Project.

ForgingJustice After 200 Years

200 Years ofthe Penitentiary: Breaking

Chains, ForgingJustice, is a year-long project

of the American Friends Service Committee

(AFSC) designed as a springboard for renewed analysis and debate on national

criminal justice policy.

The Project coincides with the 200th year

since the building of the first penitentiary

in the United States in 1790. The Religious

Society of Friends (Quakers) and others

developed the idea as an alternative to

corporal and capital punishment.

AFSC was founded in 1917, as the service

arm of the Religious Society of Friends. The

Committee felt that it was appropriate to

use this 200th year after the founding of the

penitentiary as a time for reassessment of a

model that Quakers helped create.

The Project's goals are:

_ To broaden public debate by focusing

on root causes of crime, drug abuse, violence

and on the increased imprisonment of

people of color and poor people;

_ To involve in the debate those most

affected by crime and imprisonmentAfrican Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans and poor people;

_ To change public policy on economic

and social issues connected to the crisis in

the criminal justice system;

_ To plan both long-term, fundamental

changes in the criminal justice system as

well as immediate reform.

The Project will sponsor and participate

in a variety of commu!1ity action projects. lt

will organize a series of hearings; conduct

public education tours of prisons; and act as

an information clearinghouse offering

speakers and research on model state and

national criminal justice legislation.

October 20, 1990 will be a day of nationally coordinated activities to dramatize the

issues, generate debate and develop strategic

solutions.

For more information, contact Linda

Thurston, Project Coordinator at AFSC, 1501

Cherry Street, Philadelphia, PA 19102,

215/241-7130.

.

SUMMER 1990 5

Instead of Death:

Alternatives to Capital Punishment

Until we give up the illusion that

puttingpeople to death is a

solution to the crimeproblem, we

will never develop alternatives that

willprotect us and enhance the

value ofhuman life in a civilized,

just society.

-The Fellowship of Reconciliation

n 1952, sociologist Arthur Lewis

Wood, in one of the few published

examinations of substitutes for the

death penalty, observed that the use of

life sentences "has caused an excessive

accumulation of inmates in many of our

state prisons. The pressure of this

condition and perhaps the increasing

acceptance of individualized treatment

I

have encouraged, at least in some states,

the more frequent use of the traditional

powers of executive clemency and court

discharge by selective release of these

prisoners."l

More recently, the Fellowship of

Reconciliation's Capital Punishment

Program probed more deeply into specific

actions society could take when confronted by violent behavior instead of

the death penalty. Life imprisonment,

they suggest, "provides for something

that death does not-an opportunity for

the natural maturation process to occur

and for society to re-examine its responses to behavior."2 The Fellowship

concluded that hospitalization and medical treatment for some capital offenders

and restitution and compensation for

victims merit further examination.

In the mid-1970s, the prestigious

Committee for the Study of Incarceration

boldly proposed that sentences longer

than five years should be abolished

except for certain types of murder or in

exceptional instances requiring predictive restraint. In the case of murder, the

committee outlined the following

sentencing scheq.,e:

Murder, the·rftost serious ofcrimes,

presents spectalproblems because of

the diverse circumstances under

which it is committed. Having a single

presumptivepenalty might require

unduly wide discretionary variations

to accommodate killings Of varying

degrees ofgravity. It may bepreferable

to prescribe separatepresumptive

penaltiesfor distinct kinds Of murder:

(J) murders stemmingfrom personal

quarrels, (2) unprovoked murders of

strangers, (3) political assassinations,

There are various alternatives to the death penalty. Most state laws provide for life sentences for capital murder

which severely limit or eliminate the possibility of parole. At least 10 states have life sentences under which

parole is not possible for 20, 25, 30 or 40 years and at least 18 states which have life sentences with no

possibility of parole at all.

D

States with

States with

III States with

If[] States with

III States with

III States with

•

death penalty•

death penalty, or life without parole.

death penalty, or life without parole for at least 20 years.

no death penalty.

no death penalty, with life without parole.

no death penalty, with life without parole for at least 20 years.

Alaska and Hawaii have no death penalty and no life without parole.

6 SUMMER 1990

Source: Ronald J. Tabak and Mark J. lane, The Execution of

Iniustice: A Cost and Lack-of-Benefit AnalYSiS of the Death

Penalty, 23 loyola of los Angeles, l. Rev., 126-127 (19901.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

and (4) especially heinous murders,

such as those involving torture or

multiple victims. Five years might be

the norm for the personal-quarrel

situation, with longerpresumptive

sentencesfor the other three categories.

This approach would have the

additional advantage that the

homicides that cause the mostpublic

outrage-those in the last three

categories-would be

dealt with separately:

were there only a single

presumptivepenalty, it

would tend to become

inflated to accommodate

the more shocking

homicides.3

Except for these and

several other proposals,

abolitionists have given inadequate

attention to what should replace capital

punishment. Instead, they have largely

focused, justifiably, on restricting and

ending its use. Unfortunately, in the

absence of detailed discussion of alternatives to the death penalty, life without

parole, currently the most politically

acceptable alternative, overshadows

more humane options. In the absence of

broader discussion, the tendency is to

define penalties by their eqUivalency

with the capital penalties they are

supposed to replace. Life without parole

as an alternative to the death penalty is

but one example of the way "reform"

proposals are shaped in reaction to,

instead of as a challenge to, conservative

crime control strategies.

A Historical Dilemma

Capital punishment's greatest

strength-for those who support it-is the

clarity of its retributiveness, the sense

that capital offenders got what they

deserved or, at least in the caSe for

murderers, they got what they gave. As

with the clanging of the prison cell door,

the clarion call for capital punishment is

that the death penalty is concise in its

finality not only for the executed but

also for those who apply it or approve its

application. Once done, justice is done. For

death penalty proponents, justice is more

a specific action than a process. Once

done-proponents like to think-there's

nothing more to think about; society no

longer bears any responsibility.

In times past, the death penalty was

meted out for a wide variety of offenses.

Nineteenth and twentieth century

advocates against the death penalty

succeeded in whittling away the number

of capital crimes. Their ally was the

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

inherent disproportionality of killing

someone who did not kill someone else.

Ever since the death penalty was

abolished for rape, however, the major

focus of anti-death penalty strategies has

been to eliminate death penalty statut~s

for people who have killed.

~'

Historically, death penalty abolitiort~s

have been weak in suggesting altern:!';;'

tives. Generally, they've taken one 9f.lwo

approache~;

First, so~~rgue

that it s~mi>ly

isn't necessary

to propose an

alternative. The

primary struggle

is to abolish the

death penalty.

This is a handy

device because in fact it would be a nice

step forward if we simply abandoned

capital punishment regardless of whether

we knew what to implement in its place.

Nonetheless, it begs an important

question, namely, what do we do when

people kill other people? Moreover, it

leaves the door open for unsatisfactory

alternatives, e.g., life without parole.

Second, others have accepted less-thanideal alternatives. Frequently, these

alternatives are bleak and problematic in

themselves. In the mid-1800s, for instance, reformers such as Robert Rantoul

Jr. in Massachusetts succeeded in reducing

the number of offenses for which one

could receive a death sentence. But the

alternatives offered were draconian.

Rantoul suggested placing offenders in a

deep dark pit (only years before Connecticut and Maine had built prisons at

former mining sites).

Current initiatives by anti-death

penalty governors, such as Michael

Dukakis of Massachusetts or Mario Cuomo

of New York, to garner support for life

without parole can be seen in this same

dim light. What they offer is a political

ameliorative, a strategy to convince

enough legislators to keep the death

penalty from becoming state law.

Unfortunately, there is much to be said in

favor of this approach-it may indeed

keep people from being executed-but it

nonetheless also begs the question-what

do we do when people kill other people?

Seeking Alternatives to the Death

Penalty

Historically, despite periods of waning

public support for capital punishment,

the level of public support has long

confronted death penalty opponents.

University of California historian Louis P.

Masur, in his new study, Rite ofExecution: Capital Punishment and the

Transformation ofAmerican Culture,

1776-1865, observes that antebellum antideath penalty activists, buoyed by

successes in reducing the number of

capital offenses but nonetheless confronted by seemingly strong public

support for capital punishment, feared

that "the total abolition of the death

penalty was still a long way off."4

Public sentiment favoring the death

penalty is of\en basted over the gristle of

political deblites on capital punishment.

But politicl(fleaders frequently overestimate the retributiveness of the public.

Political leaders commonly fail to understand what the public wants when it

raises its voice in capital cases, and rarely

use their leadership positions to inform

and influence public understanding.

According to criminologist Roger Hood,

"the suggestions that attitudes to the

death penalty are so deeply embedded

that they are impervious to the impact of

information about its administration and

effects has to be placed alongside the fact

that in many countries opinions have

changed, and quite markedly, over

relatively short periods of time."5

Hood, who directs the Centre for

Criminological Research at Oxford

University, turns to recent American

history for proof. In 1953, he writes, 66%

of Americans were said to favor capital

punishment. This figure was to fall to

40% in 1966 before rising to 71% in 1986.

"This would seem to indicate," Hood

surmises, "that there is a substantial body

of non-ideologically committed opinion

that can be affected in one direction or

another by information about crime and

the impact of punishment."

Indeed, sociological studies raise several

issues: first, they show that people feel

that American courts are more lenient

than they actually are; second, given

information about capital offenders, the

costs of execution, and alternatives to the

death penalty, people are less inclined to

support it.

In recent years, Amnesty International

and other reform groups have begun to

describe the complexities of public

opinion on the death penalty. At a time

when newspaper articles lazily refer to

what appears to be overwhelming citizen

support for capital punishment, Amnesty

has sponsored research surveys in

California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia,

Kentucky, Maryland, and Oklahoma that

have found a groundswell of support for

alternatives.

Abrief review of several of these

SUMMER 1990 7

research projects suggests that public

support for the death penalty is not as

strong as proponents assert.6

• Californians prefer life without

parole plus restitution over the death

penalty by a margin of two to one.

Respondents to a December 1989 survey

believe that this addresses their concerns

that murderers remain in prison and that

something is done for victims. The survey

found that the public has many misconceptions about what capital punishment

"achieves." Finally, Californians were less

supportive of the death penalty when

they learned specific information about

offenders' backgrounds. Only one-fourth

of those polled, for instance, supported

executing the mentally retarded?

• Support for the death penalty among

Oklahomans would be reduced by 40% if

life without parole were substituted.

Support also diminishes among Oklahomans when the offender is a juvenile, is

mentally retarded, or has a history of

being abused as a child. Finally, Oklahomans are in a mitigating mood when

someone kills in a

"moment of rage" or is

under the influence of

alcohol or drugs.s

A Public

Information

Campaign Against

the Death Penalty

In May 1990, the

National Coalition

Against the Death

Penalty (NCADP) received a one-year

grant from the J. Roderick MacArthur

Foundation in Chicago to establish a

National Death Penalty Information

Center (NDPIC). NDPIC's primary purposes, according to Leigh Dingerson,

NCADP's executive director, are "to help

develop proactive media strategies

against capital punishment and to collect

and provide information about the death

penalty to the press."

Pessimistic views of public opinion

pervade much writing about the death

penalty and other criminal policy issues.

Several years ago, criminologists Franklin

E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins observed

that "public opinion, political pressures,

the abdication of federal courts, and the

undisciplined performance of other

decision-making institutions all combine

to create a climate in which there will

probably be more, not fewer, executions

in the near future."9

The public opinion surveys done by

Amnesty International and other reform

8 SUMMER 1990

groups suggest that, like the Berlin Wall,

the notion of a vengeful public has

cracks and is crumbling. What these

studies clearly identify is the need for

public education; they show that public

opinion is both ill-informed and open to

alternatives to the death penalty. If the ~'

NCADP's National Death Penalty Informa-:J~

tion Center and state and local anti-deatlJ.(~'

penalty groups use this information to,.. ','

help shift media and policymaker

,.

perceptions, it is possible that other

factors identified by Zimring and

Hawkins-political pressures, etc.-would

become more fertile ground for developing criminal policies that do not rely on

death as an anchor.

Interestingly, Zimring and Hawkins do

not mention any specific alternative as a

pre-condition for abolition, including life

without parole. In part, they conclude

that enlightened leadership will guide

public opinion. They also argue that once

capital punishment is abolished, people

(they refer to victims' families) will

continue to call for

the harshest penalty

available. To the

extent that this is

true-Zimring and

Hawkins neglect the

views of murder

victim families that

oppose the death

penalty-it behooves

us as a civilized

society to temper

people's choices.

However, the

central questions remain. What instead of

death? And what role do these alternatives play in helping to abolish the death

penalty?

The simplest, most direct approaches to

a particular problem, business leaders say,

are most likely to succeed at producing

results. An honest accounting of the

"benefits" of capital punishment in this

country gives us nothing to brag about:

botched, painful, supposedly "painless"

executions; increased isolation as a nation

willing to kill as a matter of state policy;

and a Supreme Court that is more willing

to speed up the pace of executions than

to probe the realities of what Yale law

professor Charles Black once called the

"inevitability of arbitrariness and

caprice" in the adjudication and administration of the death penalty.

Like earlier discussions of alternatives

to the death penalty, this article is far

from complete, but perhaps it can be used

as a foundation for exploring future

alternatives.

Victim Services: When a person kills

someone, regardless of mitigating or

aggravating factors, there are victims.

These victims may be spouses, family

members, friends, neighbors, or coworkers. Similarly, when the state kills

someone, there are also victims with

equivalent relationships to the executed

person. Heretofore, the needs (to express

anger, to receive counseling, etc.) of these

victims, on either side of the crime

victim/criminal offender equation,

rarely receive at\Cntion. Some victim

support groups lJ-jlve specific projects

working with t;fturder victim families

and at least one state has developed

guidelines for working with family and

friends of murder victims. But more

needs to be done.lO In particular, services

to victims should be available regardless

of whether an offender has been

arrested, convicted, or sentenced.

Furthermore, these services should be

provided not as part of a sentencing

scheme but simply because they are

needed.

Demystifying Viol~nce: Murder is a

violent crime. Regrettably, especially in

the United States, it is not all that

uncommon. Still, the violence associated

with homicide is frequently spoken about

in extraordinary terms. In the process, we

seem to disempower ourselves from being

able to do anything sensible to address it.

But, with exceptions, many capital

murders-even sometimes the worst of

them-derive from cumulative or

immediate circumstances that have more

comprehensible roots. We are now

becoming more aware, for instance, of

the role that physical and sexual child

abuse have in shaping violent behavior

in some people,u We need to increase our

understanding of these root causes of

violence and how we can develop social

policies and programs to prevent, not

simply respond to, crime.

Sentencing Advocacy: Both legal and

popular articles on defense work in

capital cases are replete with references

to the inadequacy of legal counsel in

many instances. Less discussed, but

perhaps equally important, is the

inadequacy of sentencing advocacy. The

problem is two-fold: First, what are the

alternatives? Second, what process should

be used to develop appropriate alternatives? In recent years, defense-based

sentencing advocacy services, like those

used in non-capital cases, have been used

in Illinois, New Jersey, and other states.

These services must develop sentencing

plans that consider broader concerns,

including those of victims and their

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

families, than is the

case in most court

proceedings. If there is

a penalty more

humane and appropriate than life without

parole, for instance,

these plans can give

substance to these

claims. They provide

the court with a

concrete method of

meting out less

drastic, more constructive penalties.

New Penalties: It

isn't necessary or

politically wise to

take convenient shortcuts while fashioning a better response to violent crime.

Several years ago, a New Jersey court

suggested victim restitution as a condition of parole for a murderer in that

state. The victim's family had not been

consulted on the plan and raised a furor.

The parole was quashed.

Justice is a process as much as it is

individual actions. Accordingly, in

looking for alternatives to the death

penalty, we need to examine broader

concerns than the standard justifications

for punishment: rehabilitation, incapacitation, deterrence, and retribution. The

Safer Society Program of the New York

State Council of Churches, for instance,

proposes a community safety/restorative

model for communities wishing to

protect themselves against violence. The

basic principles are: safety is the first

consideration of the community; offenders must be made responsible and

accountable for their behavior; victims,

survivors, and the community have been

harmed and need restoration; the basic

conflict which caused this harm needs

resolution when possible; a continuum of

service and treatment options is necessary in a variety of settings; and a

coordinated systems approach is needed

to encourage cooperation between public

and private resourcesP _

lArthur Lewis Wood, "The Alternatives to the Death

Penalty," The Annals of The American Academy (Vol.

284), (November 1952), p.7!.

'The Fellowship of Reconciliation, Instead of the

Death Penalty, Nyack, NY: Capital Punishment

Project, n.d.

3Andrew von Hirsch; Doingjustice: The Choice of

Punishments, Boston, MA: Northeastern University

Press; (1986), p.l39.

'See, Louis P. Masur, Rites ofExecution: Capital

Punishment and the Transformation ofAmerican

Culture,1776-1865, New York, NY: Oxford University

Press, (1989).

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

5Roger Hood, The Death

Penalty: A World- Wide

Perspective, Oxford

University Press, New York,

(1990), p.l55.

60ther studies include:

"Capital Punishment in •

Connecticut," (Archdioces~40f

Hartford, 1987); "Attitudes;1p

the State of Florida on the .

Death Penalty: Executiy,e:i"

Summary of a Public Qpinion

Survey," (Amnesty ~J;

International, USA, 1~lt6);

"Georgia Residents' Attitudes

Toward the Death Penalty"

(Southern Coalition on Jails

and Prisons, 1987); "New

York Public Opinion Poll: The

Death Penalty: An Executive

Summary," (Amnesty

International, USA, 1989). For

a review of the findings of the earlier of these

reports, see Russ Immarigeon, "Public Supports

Alternatives to Executions," jericho, No. 43, (Spring

1987), p.II.

7Craig Haney and Aida Hurtado, Californians'

Attitudes About the Death Penalty: Results ofa

Statewide Survey, New York, NY: Amnesty International, (1989).

'Harold G. Grasmick and Robert Bursick Jr., Attitudes

of Oklahoma Toward the Death Penalty, Oklahoma

City, OK: University of Oklahoma, (1988).

9Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins, Capital

Punishment and the American Agenda, New York,

NY: Cambridge University Press, (1986), p.149.

lOFor example, see Lyn Brown, Ruth Christie, and

David Morris, Families ofMurder Victims Project:

Final Repor~ London, England: National Council of

Victim Support, (April 1990).

llSee, Andrew Vachss, "Today's Abused Child Could Be

Tomorrow's Predator," Parade Magazine, Oune 3,

1990).

"Rev. Virginia MlIfkey, Restorativejustice: Toward

Nonviolence, Lo~i~viIIe, KY: Presbyterian Church

(USA), (1990). ··}l

Russ Immarigeon, a legislative associate with the New York State Assembly,

writes regularlyfor the NPPJOURNAL.

He is the co-author (with Meda ChesneyLind) of the repor~ Women's Prisons:

Overcrowded and Overused, that will be

available (for 13.50) in Septemberfrom

the National Council on Crime and

Delinquency, 685 Market St., Suite 620,

San Francisco, CA 94105, 415/896-6223.

FOR THE RECORD

_ Arecent report by the Correctional

Association of New York suggests that

New York State could save millions of

dollars a year in prison operation and

construction costs by expanding its use of

alternative punishments for those

convicted of nonviolent crimes.

The report, "Anti-Crime Strategies at a

Time of Fiscal Constraint," shows that the

state could save as much as $120 million a

year in operation and $600 million in

construction costs if they re-allocated

their resources by diverting nonviolent

offenders (roughly 61% of those sent to

state prison) into rigorous alternative

programs.

Atypical program for nonviolent

offenders would include mandatory

employment or vocationaIjeducational

training, drug or alcohol treatment

programs, community service, curfews

and strict supervision. The Association

also proposed early release of selected

inmates to intensive parole supervision,

community-managed residential

programs, and an amendment to the law

to allow good-time credits off minimum

prison sentences.

For information on how to obtain the

report, please write or call the Correctional Association of New York, 135 East

15th St., New York, NY 10003, 212/2545700.

_ Nearly one in four young Black men

between the ages of 20 and 29 is under

some type of correctional supervision

according to the report, "Young Black

Men and the Criminal Justice System: A

Growing National Problem." The report,

published by the Sentencing Project, also

points out that the number of young

Black men under correctional supervision

is greater than the number of Black men

of all ages enrolled in college. The 12-page

report is available for $250 from The

Sentencing Project, 918 FSt., Suite 501,

Washington, D.C. 20004, 202/628-0871.

_ Alvin}. Bronstein, executive director

of the National Prison Project, received a

Doctor of Laws degree, honoris causa,

from New York Law School on June 10,

1990. Mr. Bronstein, who is an alumnus of

the law school, also delivered the

commencement address to an audience of

over 3,000. Bronstein urged the law

school graduates to "proceed with a

commitment to moral reasoning...with a

feeling of social responsibility," noting

that "you can still make a difference." He

concluded the speech by quoting James

Baldwin: "We must continue to be

witnesses of our time; We must speak out

against institutionalized and individual

tyranny wherever we find it; Because if

left unattended, it threatens to engulf

and subjugate us all."

SUMMER 1990 9

...

Case~wReport

A PROJEO OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES ~NION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL. 5, NO.3, SUMMER 1990 • ISSN 0748- 26~§

.f;V-'

Highlights of Most

Important Cases

Mental Health Care/Medical Care

Prisoners have a substantive due process

right to avoid the involuntary administration

of antipsychotic drugs, according to the

Supreme Court's recent decision in Washington v. Harper, 58 U.S.Law Week 4249 (February

27,1990). But that right may be overcome if

medical personnel find that the prisoner

suffers from a mental disorder which is likely

to cause harm if not treated and as long as the

medication is prescribed and reviewed by

psychiatrists. As a procedural matter, the

prisoner need not be found incompetent in a

judicial proceeding and court authorization to

medicate need not be obtained. Apsychiatrist's

decision is sufficient as long as it is reviewed

by medical professionals who are not involved

in the prisoner's current treatment or

diagnosis.

In reaching these conclusions, the Court

cited the special characteristics of the prison

environment and prison officials' interest in

and duty to protect the safety of prison

personnel and other prisoners. It also relied

explicitly on the "reasonableness" standard

applied to prison regulations since Turner v.

Safley. Thus, it appears that the Court would

approve the compulsory use of antipsychotic

medications on J.tfisoners in situations in

which civilly committed persons could not be

forcibly medicated.

The Court assumed that "the fact that the

medication must first be prescribed by a

psychiatrist, and then approvedby a reviewing psychiatrist, ensures that the treatment in

question will be ordered only if it is in the

prisoner's medical interests, given the

legitimate ne~ds of his institutional confinement" 58 U.S.Law Week at 4253. In so

assuming, the Court glossed over its own prior

realization that prisons' institutional and

security considerations "can, and most often

do" impinge on prison medical services. Westv.

Atkins, 487 U.S. -------' n.15, 101 L.Ed.2d 40

(1988). The Court also ignored the fact that

what is in a person's "medical interest" is often

a matter of opinion and of values and not of

technical judgment-especially when the

10 SUMMER 1990

proposed treatment affects the patient's

mental processes and poses significant risks of

serious and irreversible side effects, as do most

anti-psychotropic medications.

The practical result of Harper will likely be

to shift most challenges to involuntary

medication to state courts applying state law.

Many states require some sort of judicial

authorization for coerced medication, either

by statute or under interpretations of state

constitutions, and some states' law makes no

distinction between prisoners and civilly

committed persons. See dissenting opinion of

Justice Stevens, 58 U.S.Law Week at 4262 n.ll.

Others-including Harper-provide for judicial

review of medication orders. In fact, Mr.

Harper may ultimately win his case; the lower

courts have not yet ruled on his state law

arguments.

In White v. Napoleon, 897 F.2d 103 (3d Cir.

1990), decided a few days before Harper, a

federal appeals court ruled more generally on

a prisoner's right to refuse medical treatment,

holding that such a right exists but that it may

be overcome "when prison officials, in the

exercise of professional judgment, deem it

necessary to carry out valid medical or

penological objectives.... [T]he judgment of

prison authorities will be presumed valid

unless it is shown to be such a substantial

departure from accepted professional

judgment, practice or standards as to demonstrate that the person responsible actually did

not base the decision on such judgment." 897

F.2d at 113.

In White, the plaintiff alleged that he

refused a course of treatment for an ear

infection because the doctor would not tell

him if the medication contained penicillin (to

which he was allergic), that the doctor

subjected him to disciplinary charges (later

dismissed), and that there was no medical or

penological justification for this conduct. The

court held that these allegations were

suffiCient to state a constitutional claim. But

this decision does not suggest what kinds of

medical or penological justifications might

suffice to overcome the right to refuse

treatment. There is little prior case law on this

subject, and the cases that do exist deal mostly

with anti-psychotic medications (see Washington v. Harper discussion above), examinations

and vaccinations for communicable diseases,

Zaire v. Dalsheim, 698 F.Supp. 57, 60 (S.D.N.Y.

1988) (diphtheria-tetanus injection); Ballard v.

Woodard, 641 F.Supp. 432, 436-37 (W.D.N.C.

1986) (tuberculosis test); Smallwood-El v.

Coughlin, 589 F.SuIP. 692, 699-700 (S.D.N.Y.)

(intake examinati.dn for communicable

diseases), or witl;1'threats to the prisoner's life,

where most courts have upheld compulsory

treatment based on the dangers to prison order

if a prisoner is allowed to die, or on the danger

that prisoners may use the threat of death to

manipulate the prison administration.

Procedural Due ProcessDisciplinary Proceedings

Arecent Supreme Court decision in a mental

health case may affect the extent of liability

in prisoners' due process suits. In Zinermon v.

Burch, 58 U.S.Law Week 33 (February 27, 1990),

the plaintiff alleged that he was denied

procedural safeguards required by state law

and due process in his admission to a mental

hospital. Hospital officials argued that their

acts, which violated state law, were "random

and unauthorized" and that the plaintiff's

only remedy was a tort suit in state court.

They cited the 1981 decision in Parratt v.

Taylor, which held that prison officers'

negligent loss of property did not deny due

process as long as the state provided a postdeprivation remedy in the form of a state

court damage suit.

The Supreme Court rejected the officials'

argument and held that Parrattdid not apply.

Admission to mental hospitals and failures to

follow required procedures are not "unpredictable," and providing pre-deprivation due

process is not "impossible"-in fact, state law

already made it mandatory. Therefore, the

Court held, a post-deprivation remedy did not

satisfy the Due Process Clause, and denial of

proper pre-deprivation procedures would be

unconstitutional. The Court also emphasized

that the defendant officials were the people to

whom the State had delegated both the power

and authority to confine citizens in mental

hospitals and the duty to observe procedural

safeguards. In effect, for due process purposes,

they are the State.

The same principles presumably apply to

prison disciplinary proceedings, administrative

segregation hearings, and other proceedings in

which a pre-deprivation hearing is required.

Thus, prison officials who violate due process

requirements will continue to face personal

liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 regardless of

whether there is a state remedy and regardless

of whether the State has created procedures

on paper that would satisfy due process when

followed.

Zinermon also clarifies who may be held

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEO JOURNAL

liable for due process violations: those whom

the State grants the power to restrict liberty

and the duty to provide procedural protections. An example of this reasoning-decided

before Zinermon but fully consistent with itis Scott v. Coughlin, 727 F.Supp. 806 (W.D.N.Y.

1990). There, a prisoner was twice

"keeplocked" (detained in his own cell) by

officers who then failed to write misbehavior

reports. State regulations permit officers to

keeplock inmates when they write them up; a

"review officer" scrutinizes their misbehavior

reports and keeplock decisions daily pending

the formal disciplinary hearing. See Gittens v.

LeFevre, 891 F.2d 38 (2d Cir.1989). The court in

Scottgranted summary judgment for the

plaintiff, noting that the officers' failure to

write misbehavior reports was a factor in the

due process violation, since the filing of the

report is what triggers all the other procedural

protections. Thus, the responsibilities placed

on low-level staff by the state regulations

ultimately form the basis for personal liability

for the due process violation.

Prisoners' right to witnesses in disciplinary

hearings has been severely limited in two

recent decisions of federal courts of appeals. In

Brown v. Frey, 889 F.2d 159 (8th Cir.1989), the

court held that prison officials could refuse to

call an officer as a witness "because to do so

would undermine prison authority by having

one guard testify against another guard" and

could refuse to call another prison official

"because he refused to offer any testimony

helpful to Brown's case and was therefore

irrelevant." Id. at 168.

We think this holding is incompatible with

fundamental fairness and with the entire

purpose of due process protections, which is to

ensure the factual correctness of the hearing

officer's decision. Cases in which staff

witnesses disagree are precisely those in which

there is the greatest likelihood of inaccurate,

false or vindictive accusations by officers, and

therefore the greatest need for a thorough

inquiry into the facts. Moreover, staff

witnesses are of crucial significance in such

cases, because inmate witnesses are almost

never believed when they contradict staff

accusations without non-inmate corroboration. As the Supreme Court has acknowledged,

when credibilitt is at issue between inmates

and staff, hearing officers "are under obvious

pressure to resolve a disciplinary dispute in

favor of the institution and their fellow

employee." Cleavinger v. Saxner, 474 U.S. 193,

204 (1985).

The notion that prison authority is

"undermined" by effective inquiry into the

truthfulness of staff members' accusations

reduces due process to a nullity. As one court

put it, in striking down a rule that effectively

prohibited the calling of staff witnesses, "If

there is preclusion of an entire class of

witnesses...the right is dissipated in a cloud of

verbiage." Dalton v. Hutto, 713 F.2d 75, 76 (4th

Cir.1983).

The right to call witnesses was impaired in

a different way in Francis v. Coughlin, 891 F.2d

43 (2d Cir.1989), in which the court held that

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

calling the prisoner's own witnesses out of his

or her presence does not deny due process. The

court relied on one of its own prior decisions,

Bolden v. Alston, which in turn relied on the

Supreme Court's language in Baxter v.

Palmigiano concerning issues of confrontation and cross-examination. In both Bolden~'

and Francis, the court simply assumed withQm

discussion that the same rules govern the .;'

calling of the prisoner's witness and the righf

of confrontation of adverse witnesses. In SO'

holding, it created a conflict between fe4~1

courts of appeals, see Bartholomew v. Wa1;Wn,

665 F.2d 915, 917-18 (9th Cir. 1982), and ;

effectively overruled well-considered district

court precedent.

In our view, both Brown v. Frey and Francis

v. Coughlin illustrate a growing tendency

toward perfunctory and one-sided analysis in

prison due process cases. Under Mathews v.

Eldridge, 424 u.s. 319, 335 (1976), all procedural

due process questions require balancing the

individual's interest, the likelihood that

existing procedures will yield erroneous

decisions and that other safeguards will help

avoid them, and the governmental interest in

avoiding additional safeguards. Decisions like

Brown and Francis contain little or no

discussion of the practical reality of prison

disciplinary proceedings: the overwhelming

tendency toward institutional bias of prison

staff against inmates. As the Supreme Court

observed, "It is the old situational problem of

the relationship between the keeper and the

kept, a relationship that hardly is conducive to

a truely adjudicatory performance." Cleavinger

v. Saxner, 474 U.S. 193, 204 (1985). In these

circumstances, the danger of erroneous

decisions is enormous and the need for

additional safeguards great. Yet this essential

element of the Mathews v. Eldridge test is

ignored by many courts.

Amore careful approach to an important

due process question is evident in Lenea v.

Lane, 882 F.2d 1171 (7th Cir.1989), in which the

court held that polygraph results may be used

in prison disciplinary proceedings. But the

court was careful to warn that due process

may require careful limits on their use. In

Lenea, the prisoner had been convicted of

aiding an escape based in part on two

polygraph answers alleged to be deceptive. The

court held that the polygraph results were

admissible as evidence and that in general

they may serve to corroborate other evidence

or may exculpate the prisoner.

Perhaps more importantly, the Lenea

decision suggests that prison officials must

carefully consider exactly what the polygraph

results actually prove. In Lenea, the evidence

against the prisoner consisted of the polygraph

results and the facts that he knew the escapees

and had spoken with one of them on the day

of the escape. The court concluded that these

facts did not add up to "some evidence" of

guilt. Knowing an escapee and being legitimately in an area where the escape may have

occurred do not support guilt of aiding the

escape. Polygraph evidence might be relevant

to the prisoner's credibility, but it did not

excuse prison officials from coming up with

some evidence that the prisoner actually

committed the offense, and a conviction

without such evidence denied due process.

Searches-Person/State Constitutions

Vermont's constitution gives more protection to prisoners' privacy than does the Fourth

Amendment, according to the Vermont

Supreme Court. In State v. Berard, No. 87-564

Oan.19, 1990), the state court rejected the

holding of Hudson v. Palmer, 468 U.S. 517, 530

(1984), that prisoners have no legitimate

expectation of pllivacy whatsoever in their

living quarters.. ~j

Although V(rmont constitutional law

generally "import[s] the 'reasonableness'

criterion of the Fourth Amendment," the

Berard court stated that "we seek to give

effect to the design of Article Eleven and

decline to follow parallel federal law, such as

Hudson v. Palmer, which tends to derogate the

central role of the judiciary in [state search

and seizure] jUrisprudence." Slip op. at 3, 5

(citation omitted). The court agreed that

prison life presents "special needs" that make a

warrant and probable cause requirement

impracticable, but it set conditions for random

searches: "(1) the establishment of clear,

objective guidelines by a high-level administrative official; (2) the requirement that those

gUidelines be followed by implementing

.

officials; and (3) no systematic singling out of

inmates in the absence of probable cause or

articulable suspicion." Slip op. at 9.

Other Cases

Worth Noting

u.S. COURT OF APPEALS

Medical Care/Mental Health Carel

Women/Qualified Immunity

Langley v. Coughlin, 888 F.2d 252 (2d Cir.

1989). In the Second Circuit, "the standards

concerning deliberate indifference to medical

needs and toleration of inhumane conditions

have been delineated to a significant degree"

(citing LaReau and Todaro), and the plaintiffs' allegations of widespread violations of

these standards are not subject to qualified

immunity as a matter of law. Even if defendants were immune as to some aspects of the

challenged conduct, "we conclude that the

allegations are so interrelated that precise

determination of the extent to which the

immunity defense is available must await factfinding."

Procedural Due Process-Disciplinary

Proceedings/Procedural Due ProcessWork Assignments/Grievances and

Complaints about Prison/

Injunctive Relief-Preliminary/Class

Actions-Certification of Classes/

Standing/Appeal

Newsom v. Norris, 888 F.2d 371 (6th Cir.

1989). Inmate "adVisors," who assisted other

SUMMER 1990 11

...

inmates in disciplinary proceedings, were

appointed for six-month terms, with reappointment at the discretion of prison officials.

Several of them were not reappointed and

alleged that this was because of their

complaints about the performance of the

Chairman of the Disciplinary Board.

The district court properly granted the

advisors a preliminary injunction reinstating

them. At 375: "It is well recognized that it is

constitutionally impermissible to terminate

even a unilateral expectation of a property

interest in a manner which violates rights of

expression protected by the First Amendment."

The district judge's credibility judgments (i.e.,

believing the prisoners) are entitled to

deference. Even minimal infringements upon

First Amendment rights constitute irreparable

harm.

The district court should not sua sponte

have converted the proceeding into a class

action and directed defendants to draft and

submit plans for training of the Disciplinary

Board and future inmate advisors. Whether to

seek class certification is up to the plaintiffs

and not to the court. The training relief

applied to new inmate advisers and the

present named plaintiffs lacked standing to

assert their rights.