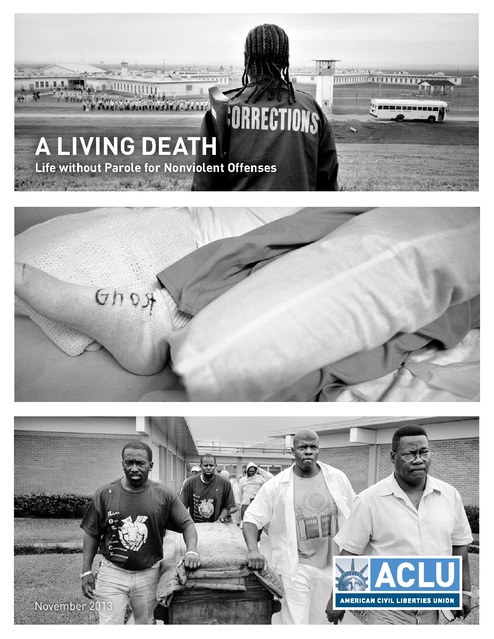

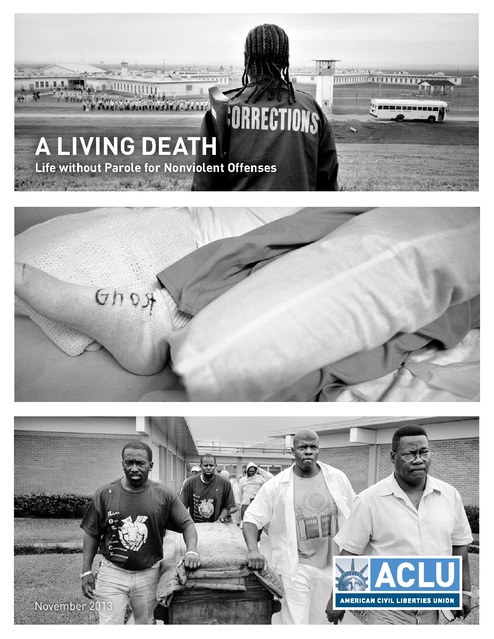

A Living Death - Life without Parole for Nonviolent Offenses, ACLU, 2013

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.