NAACP LDF - Free the Vote, the Sentencing Project, 2016

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

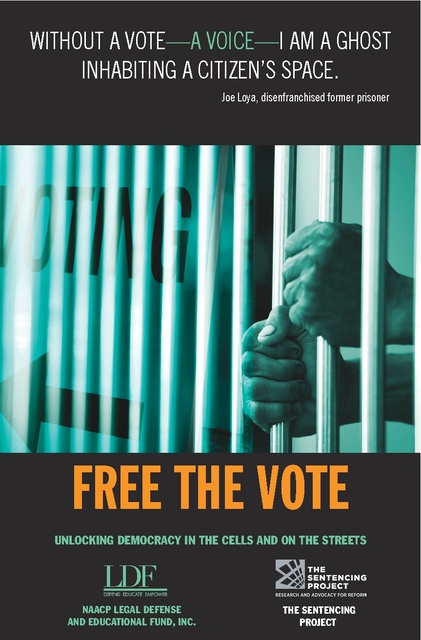

WITHOUT A VOTE—A VOICE—I AM A GHOST INHABITING A CITIZEN’S SPACE. Joe Loya, disenfranchised former prisoner FREE THE VOTE UNLOCKING DEMOCRACY IN THE CELLS AND ON THE STREETS NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. 1 THE SENTENCING PROJECT NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. Sherrilyn A. Ifill, President and Director-Counsel Janai S. Nelson, Associate Director-Counsel National Headquarters 40 Rector Street, 5th Floor New York, NY 10006 212.965.2200 Fax 212.226.7592 Washington, DC Office 1444 Eye Street NW, 10th Floor Washington, DC 20005 202.682.1300 Fax 202.682.1312 Christina Swarns, Director of Litigation Leah C. Aden, Senior Counsel Deuel Ross, Assistant Counsel Todd Cox, Director of Policy Coty Montag, Deputy Director of Litigation Monique Dixon, Deputy Policy Director & Senior Counsel Kyle C. Barry, Policy Counsel LDF’s VOTING RIGHTS PROGRAM For more than 75 years, LDF’s voting rights work has used legal, legislative, public education, organizing, and advocacy strategies to promote the full, equal, and active participation of Black people in America’s democracy. For more information, visit us at www.naacpldf.org or email us at vote@naacpldf.org THE SENTENCING PROJECT Marc Mauer, Executive Director 1705 DeSales Street, NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 202.628.0871 Fax 202.628.1091 THE SENTENCING PROJECT Founded in 1986, The Sentencing Project works for a fair and effective U.S. criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing policy, addressing unjust racial disparities and practices, and advocating for alternatives to incarceration. For more information, visit us at www.sentencingproject.org or email us at staff@sentencingproject.org 1 FREE THE VOTE Unlocking Democracy in the Cells and on the Streets The Next Phase of the Voting Rights Movement: Freeing the Vote for People with Felony Convictions Securing the right to vote for persons who have lost their voting rights as a result of a felony conviction is the next phase of the voting rights movement. Nationwide, an estimated 6.1 million Americans who have been convicted of a felony are denied access to the one fundamental right that is the foundation of all others—the right to vote. Only Maine and Vermont do not restrict voting on the basis of a felony conviction—and allow individuals to continue to exercise the right to vote from prison by absentee ballot. One in 13 Black Americans of voting age is disenfranchised because of a felony conviction, more than four times the rate of non-Black Americans. Put another way, more than 7.4% of the Black American adult population is disenfranchised compared to 1.8% of the non-Black population. (There are currently no reliable data for Latino disenfranchisement due to a felony conviction. This is largely a result of the limitations of court and corrections data on Latino individuals with a criminal conviction, particularly in past decades.) 1 Felony disenfranchisement laws are a modern version of historic voting barriers like Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, and poll taxes. Electoral Exclusion: The Past and the Present The racial disparities caused by felony disenfranchisement laws are not a coincidence. Many felony disenfranchisement laws were revised in the years following the Civil War for the specific purpose of limiting the political power of newly-freed Black people. Indeed, many state legislatures tailored their felony disenfranchisement laws to require the loss of voting rights only for those offenses disproportionately prosecuted against Black people, or thought to be committed most frequently by Black people. For example, guided by the belief that Black people were more likely to commit less serious property offenses than the more “robust” crimes committed by white people, the 1890 Mississippi constitutional convention required disenfranchisement for such crimes as theft or burglary, but not for robbery or murder. Through the convoluted reasoning of this law, one would be disenfranchised for stealing a chicken, but not for killing the chicken’s owner. Many other states, from New York to Alabama, also have historically used felony disenfranchisement laws to prevent Black people and other racial minorities from voting. Modern Day Impact on Communities of Color Felony disenfranchisement statutes have weakened the political power of Black and Latino communities. This is largely the result of the historic growth in incarceration in recent decades and disproportionate enforcement of the failed “war on drugs” in Black and Latino communities, 2 which has drastically increased the class of persons subject to disenfranchisement. Today, with 2.2 million Americans incarcerated, more than 800,000 of whom are Black Americans, the collateral effects of our nation’s reliance on mass incarceration in the “war on drugs” era are more profound than ever. Black Americans are 13% of the U.S. population, but are overrepresented in the prison population at 36%. Thus, one in 13 Black persons of voting age is denied the right to vote. The impact on Black voting strength at the state level is also devastating. In Florida, more people are disenfranchised than in any other state, with Black disenfranchisement rates exceeding a fifth (21%) of the adult Black voting age population. Similar rates can be seen in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia as well. In Alabama, 15% of the state’s Black voting age population has been disqualified from voting as a result of a felony conviction. In New York, though Black and Latino people collectively comprise about 30% of the State’s overall population, they represent more than 70% of those denied the right to vote because of a felony conviction. More than 2 million, or 36% of the disenfranchised, are Black Americans. Culture of Political Nonparticipation Felony disenfranchisement laws discourage voters and future voters, especially children, from exercising the learned behavior of voting. In so doing, these laws create a culture of political nonparticipation that discourages civic engagement and marginalizes the voices of community members who remain engaged, but who are deprived of the collective power of the votes of disenfranchised relatives and neighbors. Voices of Entire Communities Weakened Felony disenfranchisement affects more than individual voters themselves—it diminishes the voting strength of entire communities of color, which are too often already plagued with concentrated poverty, substandard housing, limited access to healthcare services, failing public schools, and environmental hazards. As a result, people in these communities have even less of an opportunity to effect much-needed positive change through the political process. 3 Prison-Based Gerrymandering In addition to disenfranchising those with felony convictions, many states and localities count incarcerated people as residents of the prisons in which they are housed, which are often in rural areas, rather than in their permanent, pre-incarceration communities, which are often in urban areas. The practice is known as “prison-based gerrymandering.” Prison-based gerrymandering compounds the harmful effects of felony disenfranchisement by artificially inflating population numbers in the rural towns, villages, and counties where many prisons are located. The racial disparities in incarceration then result in greater political influence and increased economic resources for the largely white rural areas, and a corresponding loss of resources to the urban communities from which prisoners of color usually belong. Moreover, prison-based gerrymandering violates the basic principle of “one person, one vote.” One person, one vote requires election districts to hold roughly the same number of constituents so that everyone is represented equally in the political process and each constituent has the same level of access to an elected official. For example, in the city of Anamosa, Iowa, a councilman from a prison community was elected to office from a ward which, according to the Census, had almost 1,400 residents — about the same as the other three wards in town. But 1,300 of these “residents” were actually prisoners in the Anamosa State Penitentiary. Once those prisoners were subtracted, the ward had fewer than 60 actual residents. Fortunately, New York, Maryland, California, and Delaware, and hundreds of counties have passed laws to end prison-based gerrymandering. To learn more about this discriminatory and anti-democratic practice, visit: http://www.naacpldf. org/case/prison-based-gerrymandering New Frontiers for the Expansion of Voting Rights Today, there are new frontiers for the expansion of voting rights, and old battles that remain unfinished. Regrettably, more than 150 years after emancipation, and more than 50 years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, increasing numbers of Black and Latino people nationwide are actually losing their right to vote each day, rather than experiencing greater access to political participation. 4 Fortunately, new efforts to reform felony disenfranchisement policies in states like Maryland, Virginia, and California suggest that many federal and state lawmakers from across the political spectrum are beginning to recognize the origins of these laws and to understand that felony disenfranchisement is not only discriminatory in its application, but also undermines the most fundamental aspect of American citizenship: the right to participate in the political process. For those reasons, however, reform efforts simply are insufficient. LDF and The Sentencing Project are working to eradicate felony disenfranchisement laws entirely so that there are no restrictions on voting rights because of a felony conviction, even while incarcerated, such as in Maine and Vermont, states that are overwhelmingly populated by white residents. Indeed, LDF and The Sentencing Project are leading voices in engaging the public and changing the way that Americans think about crime and punishment and its collateral consequences like felony disenfranchisement. LDF has challenged discriminatory felony disenfranchisement laws in state and federal courts across the nation, having litigated cases in New York (Hayden v. Paterson), Washington State (Farrakhan v. Gregoire), and Alabama (Chapman v. Gooden and Glasgow v. Allen), and supported other cases and advocacy in states with some of the most restrictive disenfranchisement laws like Iowa (Griffin v. Pate), Florida, Kentucky, and California. The Sentencing Project has published groundbreaking research on the history of felony disenfranchisement and its modern day impact, showing that more than six million Americans cannot vote because of felony convictions. The organization has also documented the policies and practices that have made the U.S. the world leader in incarceration and produced the racial disparities that pervade the criminal justice system. Through these and other advocacy efforts, LDF and The Sentencing Project together aim to erase these racially discriminatory laws from the books—but we need your help. What Can You Do? Together, we can empower ourselves, enhance our collective voting strength, and improve the conditions of our communities by freeing the vote for people with felony convictions. • Educate Yourself: Find out what the felony disenfranchisement policy is in your state and what efforts are underway to change that policy. Your state may permanently bar people with felony convictions from voting, may restore voting rights to people with felony convictions following release, parole, and/or probation, or may not bar people with felony convictions from voting at all. • Educate Others: Tell others in your community about the discriminatory impact of these laws. Let them know how imperative each and every vote is to effectuating change in your community, and ultimately, in your city, state, and country. • Volunteer: If you live in a state where voting rights for people with felony convictions can be restored, there may be local or community organizations that can help guide them through the restoration process, as well as assist with voter registration. There also may be community organizations in your area that: advocate for changes to and/or the eradication of felony disenfranchisement laws; work to educate people with felony convictions about their voting rights; and/or assist people in pre-trial detention who have not been convicted of a felony with voter registration and/or absentee voting. Sign up to volunteer for one of these organizations. • Take Action: Contact your state and federal representatives and let them know that you believe that these laws are anti-democratic, discriminatory, and should be swept into the dustbin of history, along with Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, and poll taxes. 5 The Fight For Voting Rights Continues. 6