Journal 9-3

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL. 9, NO.3, SUMMER 1994 • ISSN 1"Q76-769X

No EqualJustice Under the Law in India---or the u.s.

The following remarks were presented at

the International Conference on Prisons

and Punishment in New Delhi, India,

March 3-5, 1994.

No Equal Justice

am an advocate and, as such, my role

is to challenge the complacency,

actions and inactions of my colleagues

wherever I am. My purpose here is to

make you feel and think deeply, not to

offend you. I want to focus on what I

believe is the most fundamental and serious problem in all of the criminal justice

systems I know anything about, and that is

unfairness and inequality. I will do that by

talking primarily about the United States,

the system I know best.

In both the United States and India,

much homage is paid to the idea of the

balance of the scales of justice-equality

under the law. In the U.S., justice is supposed to be "blind," meaning, of course,

that all will receive equal treatment regardless of color, economic status, or

background.

I

Equal justice under the law is a myth

and a lie. Unequal justice is the reality. I

know of no criminal justice system that

comes close to providing equal justice

under the law. Certainly not the criminal

justice system in the United States and certainly not the system in India.

If you look closely, you will find the

gross inequality that exists in the American

criminal justice system. Our criminal justice and imprisonment systems are used

primarily and almost exclusively as a

~

..c

0-

tt:

~

c...

c...

z

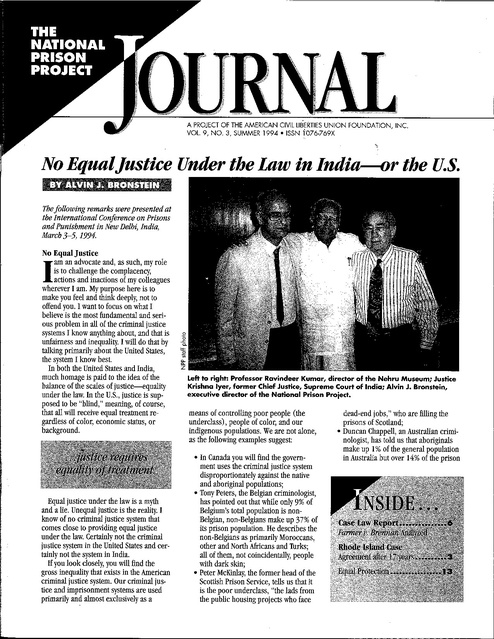

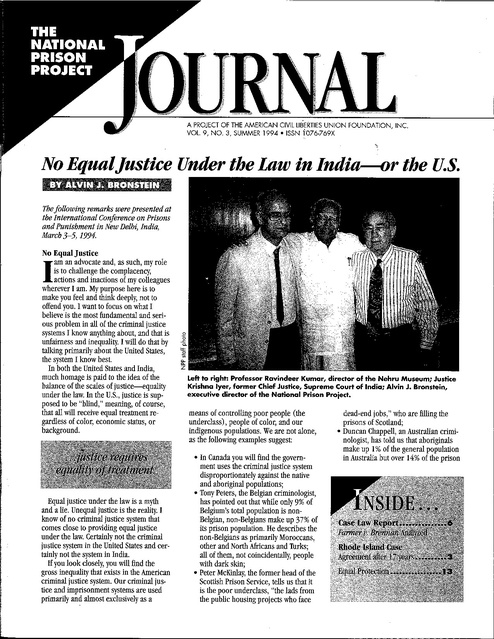

Left to right: Professor Ravindeer Kumar, director of the Nehru Museum; Justice

Krishna Iyer, former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of India; Alvin J. Bronstein,

executive director of the National Prison Project.

means of controlling poor people (the

underclass), people of color, and our

indigenous populations. We are not alone,

as the following examples suggest:

• In Canada you will find the government uses the criminal justice system

disproportionately against the native

and aboriginal populations;

• Tony Peters, the Belgian criminologist,

has pointed out that while only 9% of

Belgium's total population is nonBelgian, non-Belgians make up 37% of

its prison population. He describes the

non-Belgians as primarily Moroccans,

other and North Africans and Thrks;

all of them, not coincidentally, people

with dark skin;

• Peter McKinlay, the former head of the

Scottish Prison Service, tells us that it

is the poor underclass, "the lads from

the public housing projects who face

dead-end jobs," who are filling the

prisons of Scotland;

• Duncan Chappell, an Australian criminologist, has told us that aboriginals

make up 1% of the general population

in Australia but over 14% of the prison

population. Indeed, looking at a onemonth picture (August 1992), 28.6%

of all persons taken into police custody

were aboriginals;

• In India, there are three classes of

prisons and offenders are sentenced to

a particular prison based upon their

wealth, status and influence, not on

their criminal behavior.

Today in the United States, we have about

one and one-half million people in our

jails and prisons. Over 99% of them are

poor and 50% are people of color. One

out of three black males between the ages

of 20-29 in the State of California are in

prison or on parole or probation. In the

city of Baltimore, 50% of black males

between the ages of 16-35 are in prison,

jail or on some form of restriction (bail,

parole, community custody, etc.). In our

nation's capital the figure for that same age

group is 42%.

Duncan Chappell, in a paper delivered to

the 27th Australian Legal Convention, recalled the discussion on these issues at an

earlier symposium:!

that ofthe [former] Soviet Union's. The

USSR had been severely criticized by

Western democratic nationsfor its policy

ofkeeping dissident citizens in Siberian

and other labor camps but the United

States was incarcerating in its prisons an

equivalent underclass ofblack and other/

dispossessed minority groups.

~:

The point is, then, how can we talk

about models and values for the future of

corrections without first addressing th\:l '.

problems in our society? Or is it possible

that our society needs the poor, the people

of color, the permanent underclass, in

order to sustain our criminal justice systems and our corrections systems? If we

acknowledge, as we must, that there is no

fairness and equality under and before the

law in the criminal justice systems of most

North American and Western European

countries, how can we participate in the

travesty known as criminal justice and corrections? How can we sit around and discuss the use of the private sector, what

works in conventional programs, correctional personnel and professionalism, the

role of the media, standards and accountability, and all the rest?

The Correctional-Industrial Complex

The Canadian sociologist and former

criminal justice and corrections official,

Lorraine Berzins, recently challenged the

entire concept of punishment under contemporary criminal justice systems: 2

The United States prison crisis prompted some sharp exchanges between

North American and European participants at the Ottawa symposium. Like

their North American counterparts the

Europeans have experienced significant

increases in the number ofoffenders

being dealt with by their criminaljustice systems...,..

The true sentencing dichotomy revealed

at the Ottawa symposium among North

American andEuropean participants was

in reality an ideological split between the

two continents regarding the severity of

punishment to be imposed upon offenders. Speaking about this issue at the

Symposium, the distinguished Norwegian

criminologist, Nils Christie, sparked the

wrath ofmany ofthe United States participants by suggesting that their ideological views hadproduced apunishment

system which was not so dissimilarfrom

1 Professor Duncan Chappell, Sentencing of

Offenders: A Consideration ofthe Issues of

Severity, Consistency and Cost, Adelaide, (1991).

2

SUMMER 1994

An overwhelming body offindings

from the fields ofsocial and modern

physical sciences has shown that the

imbalance ofpower and wealth in

our society has led to inequities.

These inequities have been rationalized by those who have the power to

produce our ideological theoriestheories that define what is "right. "

Within eXisting social contexts,

many people are left at the mercy of

the social ethic ofthe dominant

group-those with the power to define for everyone which interests are

valuable, whose interests are valuable, and what rights are valuable.

Degrees of"blameworthiness" become very difficult to judge given the

imbalance ofpower and wealth.

Assigningproportional ratings is not

possible and the end result is thejustification ofthe oppression ofone

group by another....

The high collateral costs ofthis outcome, both financial and human,

2 Lorraine Berzins, Is Legal Punishment Right? The

Answer is No., NPP JOURNAL, Vol. 8, No.2, (Spring

1993), pp. 17, 18.

serve ultimately the interest ofno

one at all, save perhaps the industry

that has grown up around it.

The inescapable conclusion: pun~hmentcannotbeproportionaland

therefore cannot be justified.

Nils Christie has written extensively

about what he refers to as "the phenomena

of the economy of penal measures."3 He

has argued that, for some people, prisons

pay. "With private prisons we build into the

system a strong growth factor.,,4 This is no

minor factor in the United States and our

corrections "professionals" are part of the

problem.

For example, at the American Correctional Association's annual Congress last

year, the conference program contained

276 pages, 153 of which were devoted

entirely to advertisements (new kinds of

razor wire, restraints, various services, the

(cont'd on page 17)

3 His latest book, which examines the economic

incentives behind prison growth, should be reqUired

reading for everyone in the criminal justice field.

Crime Control as Industry: Towards Gulags,

Western Style?, University of Oslo Press, (1993).

4 Nils Christie, The Eye ofGod, Ottawa, (1991).

Editor: Jan Elvin

Editorial Asst.: Jenni Gainsborough

Regular Contributors: John Boston,

Russ Immarigeon

Alvin J. Bronstein, Executive Director

The National Prison Project of the

American Civil Liberties Union Foundation

1875 Connecticut Ave., NW, #410

Washington, DC 20009

(202) 234-4830 FAX (202) 234-4890

The Natianal Prison Project is a tax-exempt foundatianfunded proiect of the AClU Foundation which seeks to

strengthen and protect the rights of adult and iuvenile

offenders; to improve overall conditions in correctional

facilities by using existing administrative, legislative and

iudicial channels; and to develop alternatives to

incarceration.

The reprinting of JOURNAL material is encouraged with

the stipulation that the National Prison Project JOURNAL

be credited with the reprint, and that a copy of the reprint

be sent to the editor.

The JOURNAL is scheduled for publication quarterly by

the National Prison Project. Materials and suggestions

are welcome.

The NPP JOURNAL is available on 16mm

microfilm, 35mm microfilm and 105mm

microfiche from University Microfilms

International, 300 North Zeeb Rd., Ann

Arbor, MI 48106-1346.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

~II

.~

Agreement Reached in Rhode Island Prison Case After 17 Years

n 1974 a Rhode Island prisoner

named Nicholas Palmigiano filed suit

in federal court claiming that conditions in the Adult Correctional Institutions

(AC!) violated the Constitution's ban

against cruel and unusual punishment. The

case finally started to wind down in March

of this year-20 years after it began-with

the signing of an agreement which followed nearly three years of negotiations.

I

Palmigiano v. Sundlun! has a lengthy

and complex history. After an extended trial

in 1977, evidence presented by plaintiffs'

lawyers from the National Prison Project of

the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation convinced U.S. District Court Judge

RaymondJ. Pettine to declare the entire

Rhode Island prison system unconstitutionI Bruce Sundlun is !he curren! governor of Rhode

Island and has inheri!ed !he role of lead defendant.

The case has a! various limes been called Palmigiano v. Noel, Garrahy, and DiPrete.

The follow

length an

• Out of the original.

and one (Palmigian

gram after testifying

• The entire pre-trial .

of trial was under 70

• In 1977, fourfacilifi

en's." Now Rhode IS1

"medium," "sped

en's," "women's

are more people

the entire prison sy

• Bronstein recalls tha

now there are three;

• This case has seen fou

directors, and a tot .

Attorney General's 0

Department of Co

• Plaintiffs have b

lawyers from

Bronstein. St

al. Over the course of the next 15 years, the

court found it necessary to resort to various

coercive measures, including modifying

orders, sanctions, and contempt citations in

attempts to force the state to meet its obligations under the Constitution. During those

A 1985 photo of prisoners housed in storage space-a practice prohibited

under the new agreement.

.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

years, the court found that most of the

problems were attributable to overcrowding: in every instance, the court found that

overcrowding had a serious deleterious

impact on medical care and environmental

health and safety.

On January 10, 1991, Judge Pettine, who

had presided over the case from its inception and is now on senior status, held a

conference in chambers with all the parties

on the occasion of transferring the case to

U.S. District Judge Ronald R. Lagueux. In

his final order, Judge Pettine urged the parties, "Now is the time to institute safeguards that will forestall and hopefully prevent a recurrence of the past frustrating,

costly and devastating ills."

The parties have had a series of meetings

over the past three years. Negotiations to

reach the new agreement proceeded from

the parties' shared belief that existing compliance problems could best be resolved by

revising the compliance and monitoring

process to make it more efficient, and by

setting permanent population limits.

The agreement includes strong measures

to control future overcrowding and to

guarantee proper prisoner care and it

applies to existing as well as newly acqUired facilities. It states that" [a] reas not

designed and built for housing prisoners

SUMMER 1994

3

shall not be utilized for the housing of

prisoners. For example, prisoners shall

not be housed in corridors, dayrooms,

program space, office space, recreation

space or general purpose space." It also

prohibits double-ceiling in certain facilities and limits its use in others.

Governor Sundlun signed an Executive

Order in 1992 creating a Governor's Commission to Avoid Future Prison Overcrowding and Terminate Federal Court Supervision Over the ACI. The Commission was

charged with developing an action plan,

including legislation and policy initiatives,

for dealing with the state's prison population. On February 15, 1993 the Commission issued a detailed report setting forth

new approaches for the Rhode Island

criminal justice system and recommending

certain legislation. The Rhode Island General Assembly thereafter enacted legislation

providing for intermediate sanctions, and a

"Old Max," the building where maximum security prisoners are housed,

has been extensively renovated .

.Roberta Richman - changing women's lives

mong the many changes that have taken place at the ACI

since the lawsuit began, some of the most marked have

been at the Women's facilities where Roberta Richman

became warden in June of 1991. Ms. Richman took an unusual

career path to this job, beginning with a Master's degree in Fine

Arts, becoming an art teacher in prisons, running educational

and vocational services and then prison industries for all of ACI

before being appointed as warden by Director George Vose.

As warden, Ms. Richman has a very clear vision of what she

wants for the women in her care, tempered by a realistic view

of the limited resources available and the constraints of the system within which she operates. At the outset, she set herself

three goals:

1) to create a humane and safe institution environment conducive to treatment and rehabilitation;

2) to prepare women for transition back into the community

by providing sufficient educational, counseling and treatment opportunities;

3) to build partnerships with existing community agencies by

allowing them access to the incarcerated women and

sharing J;.esponsibility for their continued treatment and

support after release.

.

She stresses that there are differences between the situations

of incarcerated women and men. Most of the women have committed nonviolent crimes, have been victims of abuse all their

lives, have very limited life skills, and are mothers and primary

care givers to young children. Their sentences are usually short,

which means the time available to help them is limited.

Resources must be concentrated on preparing them for transition back into the community from the very first day they arrive.

Six months, an average sentence length, is not enough time to

do more than begin the process. The easy part is restoring physical well being, providing adequate nutrition, physical safety,

and detoxing from drugs and alcohol. The harder part is planning for continued care after they leave prison.

The ideal situation for most of these women, Ms. Richman is

convinced, would be placement instead in a community home.

4

SUMMER 1994

There they could receive help in a co

as long as they needed it and then m

own on the outside-knowing that

when life became too threatening or

temporarily to the more sheltered co

rent political climate makes such a r

next best thing, according to Ms. Ric

caring groups in the community who

prison so that when they leave they

system in place. At the same time co

pares the women to deal with the pre

face - groups meet to deal with issu

domestic violence, and parenting. Co

and children are encouraged with ext

informal setting of the recently create

Center. An intensive drug treatment

ed- 90 days in duration, holistic i

tured and restrictive-to be follow

work release or home confinement

responsible living after release. HIV

training takes place in weekly grou

mature women are trained to act as

wing; a mentoring program matches a c

with a women six months before herrel

ship continues as long as possible

grams are aimed at making long-ter

women face the world, giving them

resources to deal with the potentially

they will face when they leave prison. I

Richman is far too much of a realist to

She knows that much more is needed

training for available, well-paying jobs

economic independence and enable

lies in the community. She knows she

but she is doing an impressive job in

can, day-by-day, step-by-step, providin

that many of the women in her charge

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

Criminal Justice Oversight Committee that

would permanently control the state's jail

and prison population. 2

The process for ending court supervision of the ACI has three phases: first,

conditions at the ACI will be monitored by

a team of independent experts (monitors)

in medical services, environmental health

and safety, and inmate management and

programs. Second, after a finding of substantial compliance by the monitors, the

Department of Corrections (DOC) will

report to the court and plaintiffs' counsel

on its progress with compliance. (Reports

by monitors and by the DOC may be challenged by attorneys for the prisoners or

for the Department.) Third, once the

court finds continued substantial compliance with the new agreement, all of its

provisions will be vacated, except the popRhode Island has a unified corrections system;

the ACI has custody of pre-trial and sentenced

prisoners.

2

ulation controls, which will remain in

effect indefinitely.

If the new population caps are exceeded,

the Oversight Committee is empowered to

release prisoners early or to speed up the

parole process. Should the Committee fail

to act, attorneys from the Prison Project~'

may seek court intervention.

Only under certain specific conditions

and in certain facilities may prisoners be

double-celled: double-celled prisoners

must not be classified as maximum security; cells must adhere to the American Correctional Association standards on space

requirements; and any double-celled pris-

NPP Hosts Litigation Conference

n May 19 and 20, the National

Prison Project hosted a conference

on prison litigation. The 20 attorneys

who attended, some of them special masters

in prison cases, heard presentations and

took part in discussions on a number of

areas of current concern. John Boston of the

Prisoners Rights Project of the New York

Legal Aid Society talked about consent

decree modification and termination issues,

drawing on his experiences in the long-running New York City jails cases. There was

also discussion of the "exit scenarios" developed in the New Mexico (Duran), Hawaii

O

NPP staH attorney Mohamedu Jones

(left) talks with Jonathan Smith of

D.C. Prisoners' Legal Services Project

(right) between sessions.

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

(Spear), and Rhode Island (Palmigiano)

cases, and the implications for consent

decree modification of the Supreme Court's

Rufo decision. Modification of agreements

was addressed further in a session on the

implications of the current crime bill. The

proposed Helms/Canady Amendments on

"Appropriate remedies with respect to

prison crowding" includes a provision that

court orders and consent decrees should be

reopened for modification at a minimum of

two-year intervals. The proposed amendments also attempt to limit the use of class

action suits in Eighth Amendment cases

though there was a general sense that this

change would meet so much resistance from

judges, as well as litigators, that it was

unlikely to stand.

The conference also looked at alternatives to using the Eighth Amendment in litigating prisoners' rights. Elizabeth Alexander of the NPP introduced the session on

Statutory Causes of Action and talked about

the Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act as a means of bringing special education to incarcerated juveniles. Randy Berg

and Peter Siegel of the Florida Justice Institute discussed litigation under the recently passed Restoration of Religious

Freedom Act, which has already been used

successfully to challenge restrictions on

the religious practices ofJews and followers of the Santeria religion in prisons. The

Americans with Disabilities Act also seems

oner must be out-of-cell at least 10 hours

a day and have the opportunity for a wide

range of programs.

The state now appears to realize that it

cannot build its way out of its overcrowding problem. They recently closed their

old Medium Security Facility (known as

Special Needs) and are converting it into a

community reintegration facility.

Alvin J. Bronstein, lead counsel for the

prisoners and the executive director of the

ACLU National Prison Project, said of the

agreement, "The ACLU seeks to guarantee

that the state will achieve full compliance

with its mandates for constitutional prison

conditions and procedures in the near

future and do so in a manner that avoids

the protracted litigation of the last 17

years. We believe that the population limits

and self-monitoring and reporting process

applied to the Department of Corrections

under the new agreement, will assure that

the progress that has been made in the

Palmigiano case will continue." •

to offer a good tool for enforcing the rights

of disabled prisoners but there is still some uncertainty about how its provisions

will be interpreted by the courts.

The expense of using experts for prison

litigation, now that their costs are no

longer recoverable, prompted a debate on

ways to minimize that expense. While

there may be some ways to control costs,

it was generally felt that timely expert

tours are of such importance to the success of litigation that too much restriction

on their use would be counterproductive.

The best long-term hope is for legislation

to reverse the West Virginia Univ. v.

Casey decision.

AlvinJ. Bronstein, NPP director, who

chaired the conference, introduced the final

topiC-Public Advocacy on CriminalJustice

Policy Issues-with a question as to whether

the attorneys felt it warranted much discussion time. The answer to that question was

made clear by the longest and liveliest debate

of the conference. The participants saw influencing public opinion as key to the longterm changes they want in the current policy

of over-reliance on incarceration. If public

advocacy is to be effective, we have to give

policy makers at the state and national level

viable alternatives to imprisonment that they

can take to their electorate. Agreement on

that principle was easily reached -discussion on what those viable alternatives might

be and how they could be "sold" to the public, politicians, and policy makers was still

continuing without resolution when the conference reached its scheduled close. •

SUMMER 1994

5

~.

A PROJECT OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL L1BERTIe'S.UNION FOUNDATION, INC.

VOL. 9, NO.3, SUMMER 1994· ISSN 1074,769X

Highlights of Most

Important Cases

CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT

For the fourth time in four years, the

Supreme Court has rendered a significant

interpretation of the Eighth Amendment's

cruel and unusual punishments clause in a

prison conditions case. In Farmer v.

Brennan, 62 U.S. Law Week 4446 aune 6,

1994), the Court vacated and remanded the

Seventh Circuit's summary dismissal of a federal prisoner's claim that prison officials

failed to provide her with adequate protection from violence by other inmates. For the

plaintiff, the decision provides another

chance at winning her case. For prison litigators, Justice Souter's majority opinion is a

decidedly mixed bag.

The plaintiff is a pre-operative transsexual

who has been housed in male institutions

even though she "projects feminine characteristics" and prefers to be referred to as

"she" or "her." (The Court carefully avoided

applying any personal pronoun to her in its

opinion.) She alleged that she was placed in

the general population of the United States

Penitentiary at Tel're Haute, Indiana, where

she was beaten and raped. She further alleged that the defendants acted despite their

knowledge that the penitentiary had a violent

environment and a history of assaults and

that she would be particularly vulnerable to

sexual attack.

The Court did not dwell on these unusual

facts but treated the case as invoking the

more general duty of prison officials to protect prisoners from assault by one another.

The Court noted that it had assumed, and the

lower courts have "uniformly held," that such

a duty exists. It stated:

... [H]aving stripped [prisoners] of

virtually every means ofself-protection

andforeclosed their access to outside

aid, the government and its officials are

6

SUMMER 1994

not free to let the state ofnature take

its course.... [G]ratuitously allowing

the beating or rape ofone prisoner by

another serves no "legitimate penological objectiv[e], " ... any more than it

squares with "evolving standards of

decency." ...

62 U.S.L.W. at 4448 (citations omitted).

To establish an Eighth Amendment violation,

"the inmate must show that he is incarcerated under conditions posing a substantial risk

of serious harm." Id. (The Court declined to

say when a risk becomes substantial, since

the issue was not presented to it.)

Deliberate Indifference Redux

From these familiar generalities, the Court

proceeded to the technical issue at hand: the

definition of deliberate indifference, about

which the federal appellate cases were in

conflict. The appeals courts generally agreed

that deliberate indifference is the equivalent

of reckless disregard for risk-a view the

. Farmer Court explicitly endorsed. However,

some courts had held that prison officials

may be found liable if they disregard risks

that they "knew or should have known"

about; this standard has been termed the

"objective" or "civil law" standard of recklessness. Other courts had held that prison

officials may only be found liable if they disregard risks that they actually knew about;

this definition of recklessness is generally

applied in criminal law and has been termed

a "subjective" standard.

For prisoner advocates, the bad news is

that the Court rejected the civil law standard

and adopted the criminal law standard. It

stated, "We hold ... that a prison official cannot be found liable under the Eighth Amendment for denying an inmate humane conditions of confinement unless the official knows

of and disregards an excessive risk to inmate

health or safety; the official must both be

aware of facts from which the inference

could be drawn that a substantial risk of serious harm exists, and he must also draw the

inference." 62 U.S.L.W. at 4449. The (relatively) good news is that the Court was careful to limit the impact of its holding, with the

effect (and very likely the purpose) of curbing some extreme interpretations of the criminal standard that have appeared in lower

court cases.

The Court's approach to the question was

not one of making law but one of scrupulously applying its recent decisions, in particular

Wilson v. Seiter, 501 U.S. 294 (1991), and

Hellingv. McKinney, 113 S.Ct. 2475 (1993).

The Court thought that it was compelled to

reject the objective civil law recklessness

standard by Wilson, which declined to base

Eighth Amendment liability purely on the

existence of objectively inhumane prison

conditions. Rather, Wilson held that the

Eighth Amendment embodies a "subjective"

requirement, also referred to as a "culpable

state of mind." The Farmer Court, in effect,

declined the invitation to define the terms

"subjective" and "state of mind" in a broad

and nonliteral fashion.

In heWing to the line of Wilson v. Seiter,

the Court declined to follow its only previous

attempt to give substance to the deliberate

indifference standard. In Canton v. Harris,

489 U.S. 378, 390 (1989), the Court held

that municipal liability for inadequate police

training could be established "if the need for

more or different training is so obvious, and

the inadequacy so likely to result in the violation of constitutional rights, that the policymakers of the city can reasonably be said to

have been deliberately indifferent to the

need." The Farmer Court declined to apply

Canton's holding that liability can be based

on a risk's "obviousness" (or on constructive

notice, as Justice O'Connor had phrased it in

her Canton concurrence), since such a standard would be "hard to describe ... as anything but objective." 62 U.S.L.W. at 4450.

The Court observed that Canton's definition of deliberate indifference was an interpretation of 42 U.S.C. §1983, a statute containing no independent state of mind requirement. 62 U.S.L.W. at 4450. Canton itself had

noted that the standard it announced for

municipal liability did not turn on the standard governing the underlying constitutional

claim. 489 U.S. at 388 n.8. Canton therefore

does not govern the Court's interpretation of

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

the substantive requirements of the cruel and

unusual punishments clause.

However one views the Court's reasoning,

its holding that there are now two deliberate

indifference standards is likely to breed confusion in the lower courts, especially since

many cases will contain both kinds of deliberate indifference claims-e.g., a claim by a

sentenced county jail prisoner that he or she

was assaulted by other inmates as a result of

the deliberate indifference of line staff, and

as a result of a policy of deliberate indifference with respect to training or supervision

on the part of the municipality. The prospect

of instructing juries that deliberate indifference means one thing for one set of defendants and something else for other defendants will not be pleasing either to the trial

judges who have to do it or to the appellate

panels who will have to sort out their mistakes.

This problem is not limited to cases with

municipal liability claims. Courts have often

used deliberate indifference as a standard for

individual supervisory liability in § 1983

cases, regardless of the legal standard governing the underlying constitutional claim.

See, e.g., Gutierrez-Rodriguez v. Cartagena,

882 F.2d 553, 562 (1st Cir. 1989) (Fourth

Amendment police shooting case); Stoneking

v. BradfordArea School Dist., 882 F.2d 720,

725 (3rd Cir. 1989), cert. denied, 110 S.Ct.

840 (1990) (student sexual harassment complaint under due process clause);]ones v.

City ofChicago , 856 F.2d 985,992-93 (7th

Cir. 1988) (baseless arrest and criminal

prosecution); McCann v. Coughlin, 698 F.2d

112, 125 (2d Cir. 1983) (prisoner's procedural due process claim). Questions of

supervisory liability, like those of municipal

liability, are matters of statutory interpretation arising from Congress's supposed rejection of respondeat superior under § 1983.

See Monell v. New York City Dept. ofSocial

Services, 436 u.s. 658, 691-93 (1978). Thus,

all Eighth Amendment cases in which prisoners sue bothJine staff who are directly involved and supervisors who are alleged to be

indirectly responsible will require juries to

apply two different deliberate indifference

standards.

The best practical solution to this problem

may simply be to banish the conclusory terms

"recklessness" and "deliberate indifference"

altogether, and frame jury instructions, as

well as the special verdict forms that seem

increasingly necessary in civil rights litigation, by using only the definitions of those

terms. For example: "Do you find that defendantJones knew of and disregarded an

excessive risk that prisoner Smith would be

assaulted?" Or: "Do you find that defendant

Jones failed to act to protect prisoner Smith

from assault despite his knowledge of a subTHE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

stantial risk of serious harm to prisoner

Smith?"

Qualms and Qualifications

Despite the Court's unfavorable holding,

much of the majority opinion amounts to an

exercise in damage limitation.

{

The Court rejected the view that its holding

would allow officials to disregard obvious:,!'

dangers by cultivating ignorance of then.l.

It stated: "Whether a prison official had-the

requisite knowledge of a substalltial risk is a

question of fact subject to demonstration in

the usual ways, including inference from circumstantial evidence ... , and a factfinder may

conclude that a prison official knew of a substantial risk from the very fact that the risk

was obvious." Id. at 4451.

This is an odd sort of reasoning; in effect,

it suggests that officials will not be tempted to

take refuge in willful ignorance because of

the likelihood that factfinders will erroneously fail to give them the benefit of their ignorance. However, the Court's statement should

prove invaluable to prisoner plaintiffs for an

entirely different reason than the Court

intended: it relieves them of the burden of

going forward with direct evidence of prison

officials' state of mind. In other words, an

obvious risk, without more, creates a triable

issue of fact. This point will be crucial at the

summary judgment stage in many casesespecially those involving pro se litigants,

who may have evidence that a risk was obvious, but lack the ability to conduct effective

discovery of what prison officials knew. Since

courts often withhold serious consideration

of the appointment of counsel until after a

pro se case has survived a summary judgment

motion, the effect of this evidentiary pronouncement by the Court will be pivotal for

many litigants.

Nonetheless, the Court's argument remains

unsatisfactory for its intended purpose of

refuting the "ignorance is bliss" argument.

Suppose a prison administration purposefully

avoids knowledge of risks of violence in an

institution, e.g., by failing to maintain a system for reporting violent incidents and by

discouraging inmates from complaining and

staff from reporting incidents or threats to

their supervisors. Can they still be held

liable? One appellate court has stated that

"[g] oing out of your way to avoid acquiring

unwelcome knowledge is a species of intent"

sufficient to establish recklessness under the

criminal law standard. McGill v. Duckworth,

944 F.2d 344,351 (7th Cir. 1991), cert.

denied, 112 S.Ct. 365 (1992). The Farmer

opinion gives no evidence that the Court considered this point.

The Court did, however, deal definitively

with one recurrent issue in prison violence

litigation: the specificity of the threat of which

prison officials must have had knowledge.

The Court stated:

The question under the Eighth

Amendment is whether prison officials,

acting with deliberate indifference,

exposed a prisoner to a sufficiently substantial "risk ofserious damage to his

future health, "... and it does not matter

whether the risk comes from a single

source or multiple sources, any more

than it matters whether a prisonerfaces

an excessive risk ofattack for reasons

personal t'eJ. him or because all prisoners

in his situation face such a risk.

62 U.S.L.W.at 4451 (citation omitted).

This holding amounts to a broad ratification of the body of case law finding prison

officials liable for violence resulting from

generalized failures of prison administration-or, as the case law puts it, "systematic

deficiencies in staffing, facilities or procedures [that] make suffering inevitable.... "

Fisher v. Koehler, 692 F.Supp. 1519, 1561

(S.D.N.Y. 1988), affd, 902 F.2d 2 (2nd Cir.

1990). Such deficiencies include the failure

to classify and separate aggressive and vulnerable inmates, inadequate staff supervision,

overcrowding, the lack of reporting and

investigating systems for threats and assaults,

and so forth. See, e.g., LaMarca v. Turner,

995 F.2d 1526 (1Ith Cir. 1993), cert.

denied, 114 S.Ct. 1189 (1994); Butler v.

Dowd, 979 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1992);

Redman v. County ofSan Diego, 942 F.2d

1435, 1445, 1448 (9th Cir. 1991) (en

bane), cert. denied, 112 S.Ct. 972 (1992).

The Court's acknowledgement that constitutionally significant risks to prisoners' safety

may be found at different levels of generality

may provide a fruitful approach to the "ignorance is bliss" defense. Instead of asking

"Did the warden know that prisoners were at

substantial risk of assault?" one might ask,

"Did the warden know that the failure of a

prison administration to monitor violence, or

the failure to classify inmates, can itself create or aggravate the risk of assault?" It may

be that prison officials' general knowledge of

the dynamics of prison life, and not just their

knowledge of conditions inside their own

institutions' walls, may create a triable question of deliberate indifference.

Curbing the Seventh Circuit

Prisoner advocates were concerned not

only with the disadvantages of the criminal

law standard but with the radically anti-prisoner gloss placed on it by the Seventh Circuit.

That court stated that prison officials may not

be held liable unless they possess "actual

knowledge of impending harm easily preventable,"]ackson v. Duckworth, 955 F.2d

21, 22 (7th Cir. 1992) (emphasis in original,

citations omitted), and that they must be

SUMMER 1994

7

shown to have exposed the plaintiff to a risk

"because of, rather than in spite of, the risk

to him." McGill v. Duckworth, 944 F.2d at

350 (Easterbrook, J.) (emphasis in original),

citing PersonnelAdministrator v. Feeney,

442 U.S. 256, 279 (1979). The lack of apparent doctrinal support for these propositions

did not impair the vigor with which the

Seventh Circuit asserted them or the willingness of other courts to accept them uncritically. See DesRosiers v. Moran, 949 F.2d 15,

19 (1stCir. 1991);Morellov.james, 797

F.Supp. 223, 234 (W.D.N.Y. 1992).

The Seventh Circuit gloss does not survive

Farmer. The assertion that officials must be

shown to act, or fail to act, "because of,

rather than in spite of," the risk to the prisoner is plainly contradicted by the Farmer opinion, which states: "Under the test we adopt

today, an Eighth Amendment claimant need

not show that a prison official acted or failed

to act believing that harm actually would

befall an inmate; it is enough that the official

acted or failed to act despite his knowledge

of a substantial risk of serious harm." 62

U.S.L.W. at 4450 (emphasis supplied).

Similarly, the Seventh Circuit's requirement

of "impending harm" is incompatible with the

Farmer Court's invocation of Helling v.

McKinney, which held the risk of "serious

damage to [a prisoner's] future health"

actionable. Id. at 4451, citing Helling. Since

Helling refers to harm that may occur "the

next week or month or year," and specifically

addresses a risk (second-hand tobacco

smoke) of harm that may remain latent for

many years, it can hardly be maintained that a

known risk of assault must be "impending"

before officials are required to act to avert it.

The Seventh Circuit's requirement that

harm be "easily preventable" falls for the

same reason. The Court relied on Helling for

the proposition that" [a] prison official's duty

under the Eighth Amendment is to ensure

'reasonable safety.''' It is hard to argue that

prison officials act reasonably if they do only

what is easy in theJace of a risk of death,

rape, or other serious injury.

The Problem of Injunctive Cases

The Farmer opinion is most ambiguous in

addressing the plaintiff's claim for injunctive

relief, which the Court directed the district

court to address on remand. Quoting Helling

v. McKinney, it stated that deliberate indifference '''should be determined in light of the

prison authorities' current attitudes and conduct,' ... at the time suit is brought and

persisting thereafter." It added that "to survive summary judgment, [the plaintiff] must

come forward with evidence from which it

can be inferred that the defendant-officials

were at the time suit was filed, and are at the

time of summary judgment, knowingly and

8

SUMMER 1994

unreasonably disregarding an objectively

intolerable risk of harm, and that they will

continue to do so ... ". 62 U.S.L.W. at 445152. However, it added in a footnote that if the

evidence supported the existence of an

"objectively intolerable risk of serious injury,

the defendants could not plausibly persist in

claiming lack of awareness ...." Id. at n.9.

Thus, it appears that in reality, whatever the

state of the defendants' knowledge at the time

the complaint was filed, the suit itself may '.

provide defendants with sufficient knowledge

to make out the subjective element of the

claim. Presumably this is true at the summary

judgment stage as well as later-especially

since a claim dismissed because of the defendants' lack of knowledge at the time of the

complaint could simply be refiled alleging the

subsequent enhancement of their knowledge.

The Court then added that its holding "does

not mean ... that inmates are free to bypass

adequate internal prison procedures and

bring their health and safety concerns directly

to court." For this proposition, it cited a 1943

case about equity jurisprudence, and added

that "an inmate who needlessly bypasses such

procedures may properly be compelled to

pursue them." Id. at 4452. The Court also

observed that" [w] hen these procedures produce results, they will typically do so faster

than judicial processes can." 42 U.S.L.W. at

4452. Unfortunately, the Court does not define under what circumstances this suggestion

of a new exhaustion requirement should

apply.

This portion of the Court's opinion reflects

some naivete about the practicalities of

prison life. Complaints of threats to prisoners' physical safety are generally not handled

through formal grievance or complaint procedures, but through direct communication

with security staff. There are two reasons for

this. First, the complaints are often too urgent

to await the processes of even an efficient

grievance system. Second, grievance systems

are not necessarily confidential. An inmate's

grievance may pass through the hands of a

number of staff members and, in many cases,

inmates, since grievance systems typically use

inmates at least in clerical and administrative

capacities. Given the stigma attached to

"snitching" in many prison populations, the

combination of delay and the risk of disclosure makes grievance systems an unattractive

option for inmates in fear. If the Court's statement implies that an inmate who has complained fruitlessly to security staff must additionally go through the formalities of a grievance process, it is seriously misguided.

Presumably-and consistently with other

aspects of equity jurisprudence-a prisoner

who seeks a temporary restraining order or

preliminary injunction and alleges an actual,

present danger to safety will still be given the

opportunity to show that he or she is at risk

of "irreparable harm" supporting such preliminary relief. See, e.g., Mitchell v. Cuomo,

748 F.2d 804, 806 (2nd Cir. 1984) (Eighth

Amendment violations would constitute irreparable harm); Cohen v. Coahoma County,

Miss., 805 F.Supp. 398,406 (N.D. Miss.

1992) (physical abuse by jail staff would

constitute irreparable harm). Such a holding

would also be consistent with the law of exhaustion in federal prisoner litigation, which

excuses exhaustion where the administrative

procedure is "inad~quate to prevent irreparable injury." Terrellv. Brewer, 935 F.2d 1015,

1019 (9th Cir. 1991).

Like the Court's other recent Eighth

Amendment cases, Farmer involved the claim

of a single inmate. The Supreme Court has

not reviewed the merits of an Eighth Amendment class action since Rhodes v. Chapman

in 1981, and in particular has not considered

the implications of its state-of-mind requirement for such cases.

Justice White, concurring in Wilson v.

Seiter, observed that "intent simply is not

very meaningful when considering a challenge

to an institution, such as a prison system."

502 U.S. at 310. Justice Blackmun, concurring only in the result in Farmer, elaborated:

Wilsonfailed to recognize that "statesanctionedpunishment consists not so

much ofspecific acts attributable to

individual state officials, but more ofa

cumulative agglomeration ofaction

(and inaction) on an institutional

level".... The responsibility for subminimal conditions in any prison inevitably

is diffuse, and often borne, at least in

part, by the legislature.

62 U.S.L.W. at 4454 (citation omitted). For

this reason, Justice Blackmun argued that

Wilson should be overruled.

One solution to this problem lies in the difference between damage claims, brought in

an official's individual capacity, and injunctive claims, which name defendants in their

official capacities. Such claims are "in all

respects other than name, to be treated as a

suit against the entity." Kentucky v. Graham,

473 U.S. 159, 165-66 (1985). This approach

lends itself to a focus on "the combined acts

or omissions" of the state's agents, Leer v.

Murphy, 844 F.2d 628,633 (9th Cir. 1988),

rather than the search for a particular "bad

guy" whose individual culpability could support liability. (This point is argued more fully

in the journal, Vol. 8, No.4 [October 1993]

at 8-9.)

Farmer seems to assume that the subjective

element of the plaintiff's injunctive claim is to

be assessed in the same way as that element

of her damage claim, although the issue of

capacity was not raised. Additionally, the

Court observes, in connection with its discusTHE NATIONAL PRISON PROJEG JOURNAL

sion of Canton v. Harris, that "considerable

conceptual difficulty would attend any search

for the subjective state of mind of a governmental entity, as distinct from that of a governmental official." 62 U.S.L.W. at 4450.

(It is not clear why that is so. Astandard that

imposes liability where an official "knows of

and disregards" an unacceptable risk seems

readily adaptable to entity liability as long as

the knowledge exists at a reasonably high

level within the entity. See Alberti v. Sheriff

o/Harris County, Texas, 978 F.2d 893, 89495 (5th Cir. 1992) (finding of deliberate

indifference was supported by evidence "that

the state knew that by refusing to accept

felons it was causing serious overcrowding in

Harris County jails") (emphasis supplied),

cert. denied, 113 S.Ct. 2996 (1993).)

However, the Farmer Court did not have a

systemic claim before it and did not purport

to address such cases. Farmer's injunctive

claim involves the actions or inactions of

particular identified officials with respect to

a particular inmate, and not with the constraints that other state actors (including the

legislature) may have placed on them, or with

systemic deficiencies resulting from policies

or absence of policy for which responsibility

is diffuse. This kind of distinction has been

acknowledged in other cases. See LaMarca v.

Turner, 995 F.2d 1526, 1542 (1Ith Cir.

1993), cert. denied, 114 S.Ct. 1189 (1994)

(citing "the institution's historical indifference" as a basis for injunctive relieO;

Hoptowit v. Spellman, 753 F.2d 779, 782

(9th Cir. 1985) (declining to reevaluate liability based on turnover in prison administration because the "personal conduct of the

principal named defendants" was not the

focus of the case); see also Mayor v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605

(1974) (barring an injunction based on conduct that was limited to the tenure of a single

departed official).

Thus, the relevant distinction for purposes

of the method of assessing deliberate indifference may not-,be the formal and technical one

between individual and official capacity, but a

practical one based on the degree to which

the complaint's claims are systemic in nature

and the relief sought goes to the functioning

of the institution and not the treatment of an

individual prisoner. But these comments are

speculative at best, and will remain so until

the Supreme Court finally elects to examine

the implications of its recent decisions for

institutional litigation.

PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESSDISCIPLINARY PROCEEDINGS

In the last Journal, I commented on two

Second Circuit opinions suggesting that defective prison disciplinary proceedings do not

deny due process if they are reversed by adTHE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

ministrative appeal. After those comments

were written, the Second Circuit revisited the

subject and definitively rejected that view. In

Walker v. Bates, _ F.3d _ , 1994 WL

161050 (2nd Cir., April 29, 1994), the court

reasoned: "The constitutional violation ...

obViously occurred when the penalty was . ~i

imposed in violation of state law and due ,.

process requirements. Administrative appeid,

whether successful or not, cannot cut off the

cause of action any more than can a [&tate

court] proceeding.... " 1994 WL 161050 at 5.

It concluded: "The rule is that once prison

officials deprive an inmate of his constitutional procedural rights at a disciplinary

hearing and the prisoner commences to serve

a punitive sentence imposed at the conclusion of the hearing, the prison official responsible for the due process deprivation

must respond in damages, absent the successful interposition of a qualified immunity

defense." Id. at 7. The court rejected the

analogy, made in one of the earlier decisions,

to criminal proceedings, in which defendants

who prevail on appeal frequently are incarcerated pending the appellate decision. The

criminal defendant's usual lack of recourse

under 42 U.S.C. §1983 is attributable to the

fact that judges are entitled to absolute immunity, while prison disciplinary officials

are entitled only to qualified immunity. Id.

at 6-7.

Interestingly, the court still did not refer to

Zinermon v. Burch, 494 U.S. 113 (1990),

which sets out a framework for determining

when post-deprivation remedies meet due

process requirements and when they do not.

The notion of "cutting off the cause of action"

begs the question when the presence or absence of a post-deprivation remedy may well

be an element of the cause of action. However, the result in Walker is consistent with

Zinermon, as argued in this column in the

lastJournal.

The court distingUished one of its earlier

decisions by observing that the inmate in that

case would have been confined in segregation

regardless of the disciplinary conviction, and

therefore no constitutional harm resulted

from his additional, defective conviction. Id.

at 6, citing Russell v. Scully, 15 F.3d 219,

222 (2nd Cir. 1994). In light of prison officials' history of trying to "avoid their due

process responsibilities simply by relabelling

the punishments imposed on prisoners,"

Taylor v. Clement, 433 F.Supp. 585, 586-87

(S.D.N.Y. 1977), a cynic might predict that

New York prisoners will soon find themselves

receiving disciplinary sentences and commitments to administrative segregation contemporaneously. See also Sanders v. Woodruff,

908 F.2d 310, 316 (8th Cir. 1990) (dissenting opinion) ("One of the unanticipated and

unfortunate consequences of Wolff v. Mc-

Donnell has been the tendency of prison

administrators to label disciplinary actions

administrative rather than punitive to avoid

having to comply with the due process requirements of Wolff"). It would be pleasant

to be wrong.

The state Attorney General's office announced that it would seek certiorari in

Walker.

Other Cases

Worth/Noting

U.S. COURTS OF APPEALS

Correspondence-Legal and Official

Brewer v. Wilkinson, 3 F.3d 816 (5th Cir.

1993). After Turner and Thornburgh, the

Fifth Circuit cases of Taylor v. Sterrett and

Guajardo v. Estelle, which applied least

restrictive alternative standards to mail

claims, are no longer good law. Accordingly,

prisoners' incoming legal mail need not be

opened and inspected only in their presence.

An allegation that outgoing legal mail was·

opened and material removed stated claims

for denial of First Amendment rights and the

right of access to courts. The allegation that

officials' actions prevented plaintiff's document from arriving at court sufficiently

alleged prejudice to state a court access

claim.

Attorney Consultation!AIDS/Work

AssigD]Rents/Standin~eference

Casey v. Lewis, 4 F.3d 1516 (9th Cir.

1993). Under the Turner standard, prison

officials need only put forward a legitimate

government interest and provide some evidence that the interest put forward is the

actual reason for the regulations. In a challenge to the prison's denial of contact attorney visits to high-seCUrity prisoners, the district court placed an "unduly onerous burden" on the defendants by relying on their

failure to cite any incident of assault,

hostage-taking, or escape under the former

contact visit policy. At 1521: "A prison official's concern for prison security is entitled

to significant deference." The policy did not

eliminate all alternative means of court

access. At 1523: "Contact visitation with an

attorney is merely one aspect of the broad

and fundamental right of meaningful access

to the courts." The court does not weigh the

Turner factor of impact on others. The plaintiffs' proposal of searches before and after

contact visits was not an acceptable alternative because it only addressed the defendants'

concern about contraband but not hostageSUMMER 1994

9

taking and injury to staff and attorneys.

The district court should not have enjoined

the defendants' policy prohibiting HIV-positive prisoners from working in food service

because there was no evidence that any

named plaintiff was HIV positive or that any

named plaintiff had ever stated he or she was

interested in a food service job or had

applied for one.

Qualified ImmunitylLaw Libraries

and Law Books/Class ActionsEffect ofJudgments and Pending

LitigationIMootness

Abdul-Akbar v. Watson, 4 F.3rd 195 (3d

Cir. 1993). The defendants are entitled to

qualified immunity from the plaintiff's damage claims based on denial of law library

access in segregation. At 203: "... [E] ach

legal resource package must be evaluated as

a whole on a case-by-case basis." "... [T]he

standard to be applied is whether the legal

resources available to a prisoner will enable

him to identify the legal issues he desires to

present to the relevant authorities, including

the courts, and to make his communications

with and presentations to those authorities

understood." (203) At 203:

With the availability ofbasic federal

and state indices, citators, digests, selfhelp manuals and rules ofcourt, along

with some degree ofparalegal assistance and a "paging system" through

which photocopies ofmaterials from an

institution's primary facility may be

obtained, we are persuaded that even a

prisoner in a segregated unit... would

not be denied access to the courts. Nor

could the absence from the satellite

library ofany particular volume or

research aid be construed as a barrier

to constitutionally required legal

access. [Footnote omitted]

The exact materials required may vary by

institution. At 204: "The hallmark of an adequate satellite system, which achieves the

broad goals of Bougds, is, in our opinion,

whether the mix of paralegal services, copying services and available research materials

can provide sufficient information so that a

prisoner's claims or defenses can be reasonably and adequately presented."

Aprior consent decree governing law

library services is to be presumed valid and

in conformity with the law; the district court's

view that it did not provide adequate court

access at most demonstrated that the parameters of the law were uncertain.

Once the plaintiff was released from the

segregation unit, he had no further interest in

the library resources available on that unit,

and his claim was moot. The "capable of repetition, yet evading review" doctrine applies

only to deprivations that are too short in

10

SUMMER 1994

duration to be fully litigated during their exisattorney demanded it. The defendants did not

tence and that the same complainant is reause the transfer to argue that the plaintiff's

sonably likely to be subjected to again. The

claims were moot, and the plaintiff failed to

court rejects the district court's conjecture

bear the burden of proof on the causation

that the plaintiff "could again" be placed in

issue.

segregation. In any case, since the defendants

'; Evidentiary Questionslfrial

had implemented the legal access plan

approved by the district court and said they

Davidson v. Smith, 9 F.3d 4 (2nd Cir.

intended to stick to it, there was no likeli-' 1993). The district judge ruled that the

defense could not refer to the plaintiff's psyhood that he would be subjected to the same ','

deprivations.

chiatric history (institutionalization during

1972-76) during his civil trial, in which he

Procedural Due Processalleged that a correctional officer had deProperty/StandingiAttorneys'Fees

stroyed some of hisclegal papers. This testiStewart v. McGinnis, 5 F.3d 1031 (7th Cir.

mony was not harmless error, despite a curative instruction.

1993). The plaintiff's allegation that his property was taken in shakedowns without complying with the regulation requiring a "shakeConsent Decrees/Correspondencedown slip" listing the property taken and other

Legal and Official

relevant information did not state a due proKindred v. Duckworth, 9 F.3d 638 (7th

cess claim because post-deprivation remedies

Cir. 1993). Aclass action consent decree

were available in the state Court of Claims. The

limited the opening of "confidential corredeprivation was "random and unauthorized"

spondence," even in the inmate's presence,

and not pursuant to established procedures

to cases of reasonable cause to believe it conbecause those procedures reqUired shaketained contraband. The district court rej ected

down slips. This holding is contrary to Zinerthe plaintiff's motion to enforce the decree

mon v. Burch, which held that conduct was

on the ground that a consent decree could

authorized when "[t] he State delegated to [the

not require more of the defendants than the

defendants] the power and authority to effect

Constitution.

the very deprivation complained of here... and

At 641: "This view quite simply is incoralso delegated to them the concomitant duty to

rect. Consent decrees often embody outcomes

initiate the procedural safeguards set up by

that reach beyond basic constitutional prostate law to guard against unlawful confinetections ... Indeed, it is a rare case when a

ment." 494 U.S. at 138. (Another way to say

consent decree established only the bare

this is that it is the deprivation of property, not

minimum required by the Constitution." The

the denial of due process, that must have been

court also rejects the view that the decree set

unauthorized.)

forth only procedural obligations or that it

At 1037: "Due process requires that Stewart

was intended to track minimum constitutionhave a meaningful opportunity to be heard on

al standards, based on the language of the

decree itself.

'

the issue of whether the fan was contraband."

As to property for which he received a receipt,

The court rejects the defendants' argument

the disciplinary hearing at which he was conthat given the ease of smuggling contraband

victed of possessing contraband provided this

in confidential correspondence, reasonable

opportunity. In addition, regulations prOVided

grounds exist to believe that there is contrathat the prisoner had 30 days to file a grievband in every piece of incoming mail, since

ance contesting whether the property was

the wording "obViously" contemplates particcontraband; he wrote to the warden and

ularized suspicion.

asked that his letter be treated as an emergency grievance, but it wasn't, and he never

Use of Force/Summary Judgment

communicated with grievance personnel.

Norman v. Taylor, 9 F.3d 1078 (4th Cir.

The plaintiff lacked standing to seek

1993). The plaintiff alleged that he took a

injunctive relief because he had been transdrag of an inmate worker's cigarette and an

ferred to a different prison. Even if his comofficer ran up and hit him with his keys. The

plaint was construed to address the entire

officer said that the plaintiff was not only

prison system, he would lack standing.

smoking but yelling, and denied he ever

Shakedowns were conducted every 60 days

threatened or hit him. The district court held

but the plaintiff said he had had property

that the plaintiff had insufficiently refuted the

confiscated only twice in one year. At 1038:

statement that he was causing a disturbance,

"We do not believe that this rate of incidence

justifying the use of force, and granted sumsupports a conclusion that Stewart is under

mary judgment.

an immediate threat of harm."

The district court should not have granted

The plaintiff was not entitled to attorneys'

summary judgment against this pro se litigant

fees on a "catalyst" theory based on the fact

without directly posing the "pivotal question"

that he was transferred 15 months after his

whether he was creating a disturbance and

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

permitting him to clarify it. At n. 1081: Under

the plaintiff's version of the facts, the defendant needed only enough force to stop him

from smoking. "Accepting this version of

events ... the act of swinging heavy, brass keys

at Norman's face clearly exceeded the amount

of force required. It is hard to imagine a

sound penological justification for using any

physical force, without any prior warning, for

such a minor violation of the jail's rules."

The facts alleged could certainly support a

finding of malicious and sadistic intent.

The plaintiff's alleged initial and lingering

pain to his hand, swelling and decreased mobility, and psychological injury resulting from the

defendant's alleged threats, is "beyond the de

minimis level" (1082). At n. 5: The threats are

"relevant to this inquiry as well."

Appointment of Counsell

Pro Se Litigation

Williams v. Carter, 10 F.3d 563 (8th Cir.

1993). The plaintiff complained of unconstitutional jail conditions. The district court

requested appointment of counsel. Before a

hearing, the plaintiff had submitted a witness

list, requesting that the court subpoena the

witnesses. Later, in response to a form order

from the court, he submitted a different list.

The district court acted only on the second,

despite the plaintiff's protests at the hearing,

apparently treating the second list as the only

one requiring attention.

The district court abused its discretion.

At 567:

We believe this action held an uncounselled litigant to too strict a standard. When a court has denied a motion

for appointment ofcounsel, it should

continue to be alert to the possibility

that, because ofprocedural complexities or other reasons, later developments in the case may show either that

counsel should be appointed, or that

strict procedural requirements should,

in fairness, be relaxed to some degree.

The district murt is directed to reconsider

calling the witnesses in the original list, especially state officials who had recently inspected the jail and inmates who were in it at the

time of the events complained of.

Access to CourtsPunishment and Retaliation

Gibbs v. Hopkins, 10 F.3d 373 (6th Cir.

1993). The plaintiff's allegation that he was

subject to retaliation for helping other prisoners with lawsuits should not have been dismissed. There is no constitutional right to

assist other inmates in lawsuits, "but prisoners are entitled to receive assistance from jailhouse lawyers where no reasonable alternatives are present, and to deny this assistance

denies the constitutional right of access to

THE NATIONAL PRISON PROJECT JOURNAL

courts." The plaintiff should be permitted to

prove that no reasonable alternatives existed

for other inmates. He should have been permitted to take discovery concerning the merits

of the defendants' claim that they kept him in

segregation because of lack of bed space.

Law Libraries and Law

Bookslfransfers

Petrick v. Maynard, 11 F.3d 991 (lOth Cir.

1993). The plaintiff's Oklahoma conviction"

was enhanced based on his prior convictions

in two other states. He attempted to obtain

legal materials to attack the earlier convictions but the prison law library did not have

them, declined to get them, and would not

authorize obtaining them through interlibrary loans.

The plaintiff's inability to challenge the

convictions that resulted in his enhanced sentence meets the actual injury reqUirement of

court access claims. The state did not meet

its obligations under Bounds. At 995:

"Having exercised its prerogative under

Bounds to afford Petrick law library facilities

rather than legal representation, Oklahoma

owed Petrick a duty to prOVide adequate legal

resources to him." In a case like thiS, the

prisoner need not identify the materials

reqUired with specificity, but "the materials

sought should be described sufficiently so

that the prison can obtain them for the prisoner without being required to perform legal

research for the prisoner.... " The prisoner

must also "articulate" (not prove) a need

for the materials.

Modification of Judgments/

Judicial DisengagementIPre-Trial

Detainees/Crowding

Inmates ofSuffolk CountyJail v. Rufo, 12

F.3d 286 (lst Cir. 1993). On remand from

the Supreme Court, the district court denied

the sheriff's renewed motions to modify a jail

conditions consent decree to permit doublecelling and denied the state Commissioner of

Correction's motion to vacate the decree entirely. The commissioner, but not the sheriff,

appealed.

The court rejects the commissioner's position that motions to vacate are determined

only by "whether the defendants are in present compliance with constitutional requirements and whether the effects of the original

violation have abated." (291) The Supreme

Court's decisions in Dowell and in Freeman

v. Pitts, which the court "tentative [ly]" believes apply generally to institutional reform

litigation and not just to school desegregation

cases (293),

... indicated that there are two conditions that must be met before a district

court is essentially obliged to terminate

a litigated decree and return the institu-

tion or programs under court supervision to the governance ofstate or local

authorities. First, the district court muse

determine that the underlying constitutional wrong has been remedied, either

fully or to the full extent now deemed

practicable... Second, there must be a

determination that the authorities have

complied with the decree in goodfaith

for a reasonable period oftime since it

was entered...

Implicit in these requirements is the

needfor the district court, before terminating the de'cree entirely, to be satisfied that there is relatively little or no

likelihood that the original constitutional violation will promptly be repeated when the decree is lifted... Whether

authorities are likely to return to former ways once the decree is dissolved

may be assessed by considering U[t]he

defendants' past record ofcompliance

and their present attitudes toward the

reforms mandated by the decree." .. ,

Ofpossible further relevance is the way

that demographic, economic, andpoliticalforces may be expected to influence

local authorities and the institution

once the shelter ofthe decree has been

lost. [Citations omitted]

The court assumes arguendo ("we neither

adopt nor reject") the standard "most favorable to the Commissioner that we can imagine

being adopted by the Supreme Court," Le.,

entitlement to termination on a showing "that

the federal violations of the type that provoked the original action have been entirely

remedied or remedied to the full extent feasible; that a reasonable period of time has

passed during which such compliance has

been achieved; and that it is unlikely that the

original violations will soon be resumed if the

decree were discontinued." (293)

Applying this hypothetical standard, the

court agrees that double-celling of detainees

is not automatically unconstitutional. At 293:

"... [B] ut we think it obViously apparent that

double-celling in very small quarters, with

lack of security against assaults, and possibly

other threats (disease) could violate due

process." It is not clear that the sheriff's

immediate plans, much less the complete

vacation of the decree, would ensure constitutional conditions, given that the facility was

designed with single-ceiling in mind. Even if

the immediate plans were accepted, unconstitutional conditions might later be recreated.

The sheriff submitted a new motion to

modify and gained some relief in a later district court opinion not yet reported.

SUMMER 1994

11

Cruel and Unusual Punishment!

Negligence, Deliberate Indifference

and IntentlPunitive Segregation/

Remedial Principles

LeMaire v. Maass, 12 F.3d 1444 (9th Cir.

1993). Rules imposed for security reasons in

a punitive segregation unit are to be reviewed

under the "malicious and sadistic" standard

of Whitley and Hudson rather than the deliberate indifference standard applied in Wilson

v. Seiter to conditions of confinement. At

1452-53:

What LeMaire complains ofare not so

much conditions ofconfinement or

indifference to his medical needs which

do not clash with important governmental responsibilities; instead, his complaint is levelled at measuredpractices

and sanctions either used in exigent

circumstances or imposed with considerable due process and designed to alter

LeMaire's manifestly murderous, dangerous, uncivilized, and unsanitary

conduct.

This holding is directly contrary to jordan

v. Gardner, 986 F.2d 1521, 1529 (9th Cir.

1993) (en bane), which reversed a similar

panel holding by the same judge and held that

deliberate indifference is applicable to security practices.

Restraints (1457): Requiring dangerous

inmates to take showers in shackles does not

violate the Constitution. "That LeMaire finds

showering in restraints difficult is merely the

price he must pay for his violent in-prison

behavior."

Exercise (1457-58): The denial of exercise privileges for most of a five-year period

was sufficiently serious to violate the objective prong of the Eighth Amendment, but was

not imposed either with deliberate indifference or maliciously and sadistically, since it

was a direct response to his own dangerous

conduct. "All LeMaire had to do was to follow

the rules." The court notes that he could

exercise in his cell, and the district court's

injunction requiring provision of tennis shoes

for this purpose was not disputed.

Punitive Segregation, Access to

Medical Personnel, Lighting (1458-59):

Placement in "quiet cells" with two solid

outer doors was not disputed to violate the

Eighth Amendment. The court rejects the

argument that the prohibition on their use

should be limited to inmates with serious

medical problems, since previously healthy

inmates may have a medical emergency or be

injured in a fall or accident. However, the

requirements that the outer door be left open

and an intercom be provided were redundant. The defendants also agreed to "modify